‘We cannot allow the terrorists to win’: Rebuilding the World Trade Center

Loading...

Seven weeks after his company was awarded the 99-year lease on the two World Trade towers in New York, developer Larry Silverstein received the news of the 9/11 terror attacks. Shortly after, Gov. George Pataki called him and asked, “What do you think we should do?” Silverstein didn’t hesitate: “We need to rebuild. ... We cannot allow terrorists to win.”

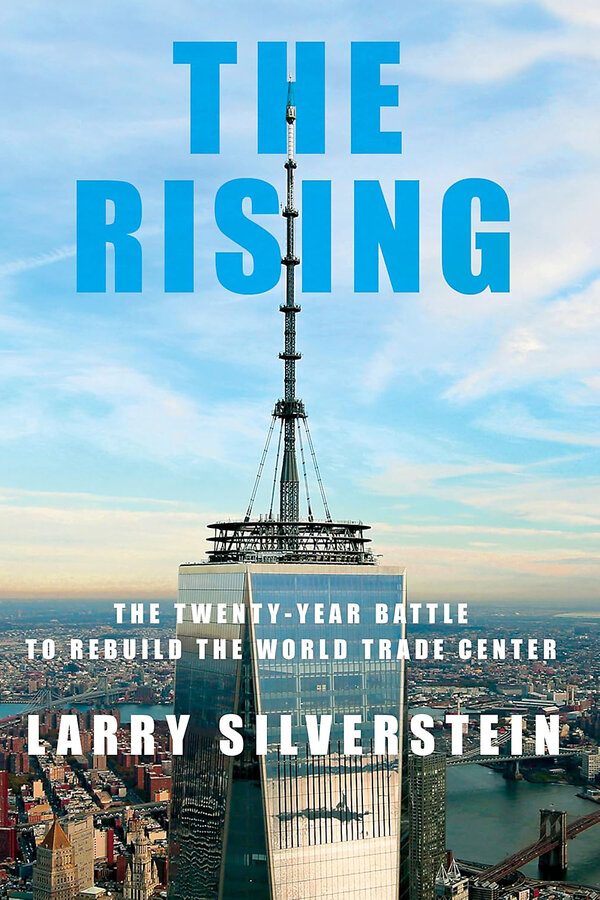

That goal would be the focus of Silverstein’s life over the next two decades, as he describes in “The Rising: The Twenty-Year Battle to Rebuild the World Trade Center.” The book digs into the bureaucracy he faced and points fingers at the institutions and individuals that he says stood in his way. The author is possessed of little literary flair but apparently commands deep familiarity with high-stakes business negotiations.

Readers will have to take Silverstein’s word because he provides no footnotes or documents to back up his assertions. That said, it would be hard to find someone as intimate with the full scope of the project’s trajectory. As Silverstein describes it: “There were so many powerful forces aligned against me. I found myself battling ambitious governors, wrongheaded mayors, incompetent bureaucrats, greedy insurance companies, and an often vindictive press.”

And that was just the business side. There were also the victims’ families to be considered in designing, planning, and constructing a 9/11 memorial and later a museum; there was the Con Edison substation to keep running; plus, the downtown subway transit hub and the New Jersey railway systems located directly under the 16-acre site had to remain functional and at the same time updated and secured. And of course, there were the buildings themselves to design, plan, and construct.

Meanwhile, Silverstein was paying $120 million a year in rent to the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey for a smoldering pit in the ground.

In describing his Sisyphean struggle, Silverstein names heroes and villains. One hero was Scott Pelley of “60 Minutes,” who reported on the delays, catching the attention of Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who took charge of the fundraising for the 9/11 memorial and museum. The author describes Bloomberg’s predecessor, Rudy Giuliani, as well as Governor Pataki, as “hell-bent on their fellow Republicans continuing to have a large say in the allocating of the promised $10 billion (later doubled to $20 billion) of federal funds that would be pouring into Lower Manhattan in the aftermath of 9/11.” And then there were the star architects, Daniel Libeskind (who developed the master site plan as well as One World Trade Center) and Santiago Calatrava (the Oculus and Transportation Hub), who, Silverstein argues, placed grandiosity and ego over deadlines, cost, and functionality. Libeskind’s site plan was kept, but his tower design was scrapped. Enter David Childs, whose design for One World Trade Center stands today.

All along, Silverstein had a vision: Build it and they will come, and in the end he built three towers to accommodate retail spaces, offices, and residences. Today, looking out from his office, Silverstein sees a neighborhood that didn’t exist 23 years ago. “A neighborhood that [he] helped to create.”