A primer on climate change that tackles both hope and despair

Loading...

The letter C might be for Climate Change. But it is also for Complicated. And Challenging.

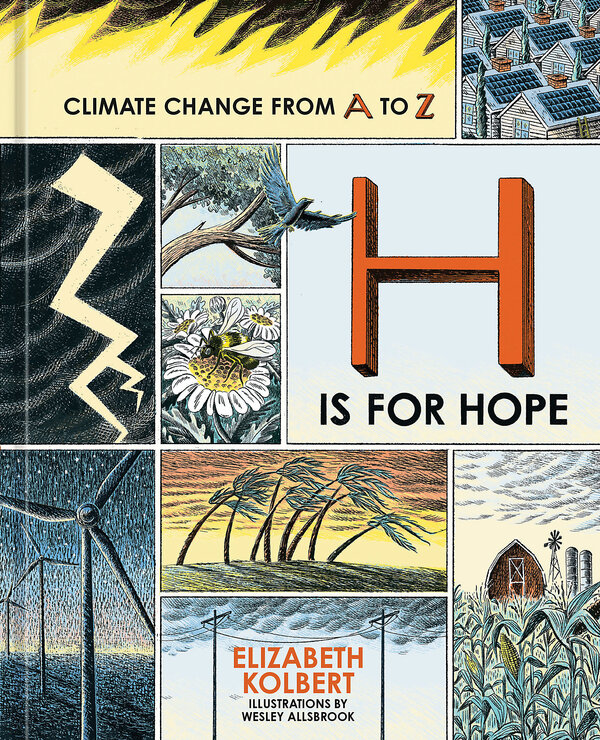

Such is the take-away from “H Is for Hope: Climate Change From A to Z.” This alphabetical collection of essays, written by Elizabeth Kolbert and vividly illustrated by graphic artist Wesley Allsbrook, gives a primer of sorts on key climate topics, from green concrete to electrification to international treaties, one for each letter of the alphabet.

Kolbert is one of America’s preeminent science journalists, whose book “The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History” won the 2015 Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction. She has written about everything from carbon capture technology to electric aviation for The New Yorker, and many of the essays in “H Is for Hope” are shortened versions of those articles.

For a broad audience, this works. The information is digestible, if not as intricately crafted as her long-form pieces, and her essays introduce the breadth of topics that are commonplace in today’s mainstream climate conversation.

But there is something inherently provocative about a beautiful book focused on an existential crisis, and at times Kolbert seems to lean into this. It can leave one slightly unsettled. Is “H Is for Hope” a coffee-table book or a misnomer? A graduation gift or a piece of subversive art? An encyclopedia, an essay collection – or perhaps a paradox, like global warming itself?

Take the actual C entry. It comes, of course, after A, which Kolbert gives to Svante Arrhenius, who created the first climate model in 1894, and after B, echoing climate activist Greta Thunberg’s 2021 “Blah, blah, blah” speech. The teen, speaking at the Youth4Climate summit in Italy, criticized world leaders for talking a good game about mitigating climate change but doing little.

C, here, is for Capitalism. And in a breezy, seven-paragraph essay, Kolbert summarizes the primary critiques lobbed against the world’s dominant socioeconomic system – arguments familiar to those of us who write about climate change – and explains how they are connected to global warming.

“Climate change can’t be dealt with using the tools of capitalism, because it is a product of capitalism,” she writes, detailing one school of thought.

Critics have argued that mainstream climate journalism tends to lean Democratic and progressive, and, with essays like this one, Kolbert’s book follows this trend.

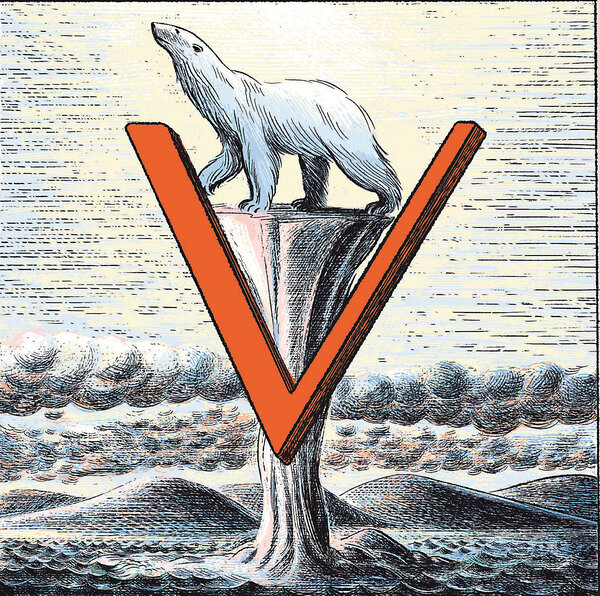

But climate journalism can also be C for Contradictory. The unequivocal reality of a warming Earth (see T for Temperatures) can crash into subjective politics (R for Republicans) and scientific debates (W for Weather). Optimism can turn into despair – although despair itself has become, among climate activists, a forbidden place to land. Indeed, in “H Is for Hope,” there are two sentences under D, each highlighted on their own blank pages.

“Despair is unproductive,” reads the first.

“And it is a sin,” says the second.

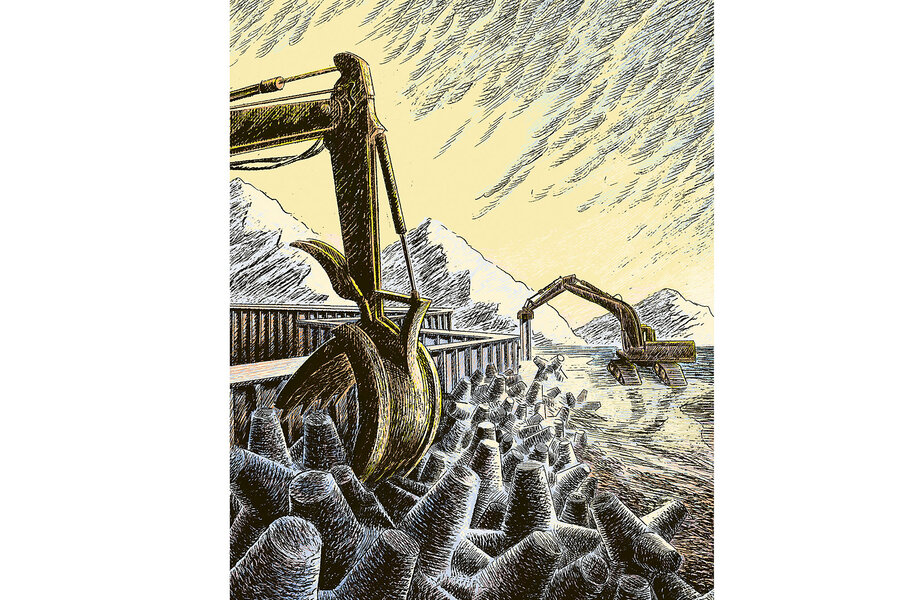

The set of essays includes topics such as innovation, technological development, and humanity’s ability to overcome, illustrated by line drawings of smokestacks, birds, lightbulbs.

But then, lest we get too comfortable with these optimistic essays, Kolbert points out that these are all Narratives (N). They are the stories we tell ourselves to keep discouragement at bay. She quotes climate researchers who say that tales of “doom and gloom” hinder climate action, while positive narratives empower. She references Christiana Figueres, the Costa Rican diplomat who paved the way for the Paris climate accord.

“Do you know of any challenge in the history of humankind that was actually successful in its achievement that started out with pessimism, that started out with defeatism?” Figueres asks. “There isn’t one.”

But it’s hard not to sense a bit of journalistic, or perhaps Thunberg-like, skepticism on Kolbert’s part. On the one hand, a reader senses that Kolbert wants to be positive, but on the other, she seems unconvinced of the success-story narratives when it comes to climate change. (“Blah, blah, blah.”)

In her final essay, “Zero,” Kolbert is standing by the Hoover Dam and the dwindling Colorado River. Her Z, it turns out, is not about Net Zero or Zero Carbon or any of those other buzzwords of climate resilience; it is for Ground Zero.

“Climate change isn’t a problem that can be solved by summoning the ‘will,’” she writes. “It isn’t a problem that can be ‘fixed’ or ‘conquered,’ though these words are often used. It isn’t going to have a happy ending, or a win-win ending or, on a human timescale, any ending at all. Whatever we might want to believe about our future, there are limits, and we are up against them.”