Sweating over a hoodie: The hurdle to making garments in the US

Loading...

Since the advent of the North American Free Trade Agreement in 1992 and the creation of the World Trade Organization a year later, manufacturing jobs in the United States have evaporated. Industries moved their production to other countries with less expensive labor. And few segments of American manufacturing have been hit harder than the textile and apparel industries.

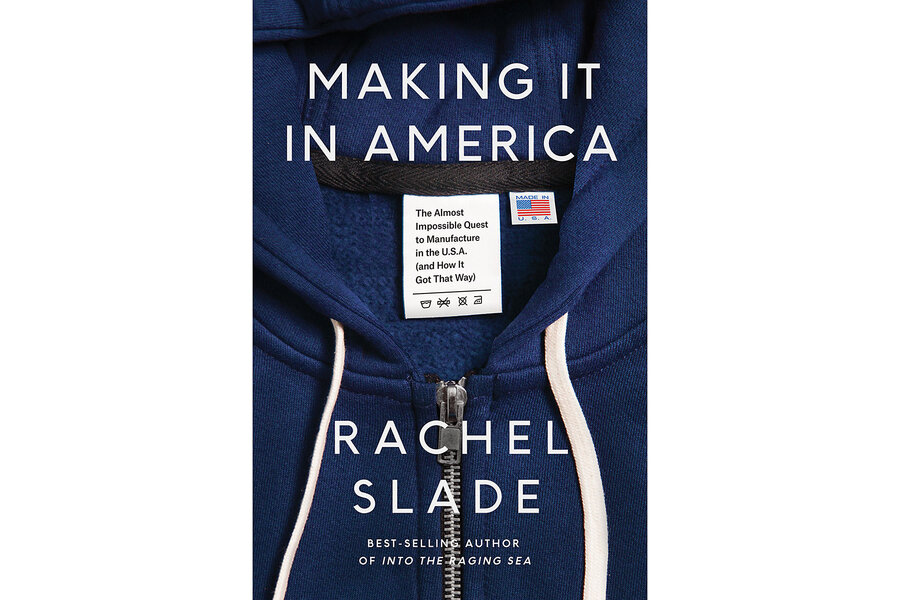

In “Making It in America: The Almost Impossible Quest To Manufacture in the U.S.A. (and How It Got That Way),” Rachel Slade tells us that 50 years ago, almost everything Americans wore was made in the country. But by 2017, “even though Americans spent $380 billion on apparel and footwear, nearly all of it [was] made somewhere else.”

Could an American clothing company, using domestically sourced materials and paying workers a union-scale wage, succeed in this era of global trade? To answer this question, Slade tells the story of an idealistic young couple whose goal was to manufacture a hooded sweatshirt.

Ben Waxman, a Maine native, was familiar with the history of New England’s once-thriving textile industry. As a union organizer who traveled around the country, he saw that “unchecked trade was deconstructing the economy from the top down,” with union jobs becoming increasingly scarce. Eventually, a burned-out Waxman returned to Maine with a “dream of building a business that made things.”

In October 2015, he and his wife, Whitney, established American Roots clothing company. They vowed to be “uncompromising” in their commitment to use only American-made products and to ensure the welfare of their employees.

Slowly the business began to grow, but pitfalls were everywhere. Few suppliers could meet their rigid “American only” requirement. Their key supplier suddenly closed its Massachusetts factory and sent most of its manufacturing to Asia. Subcontractors and suppliers didn’t deliver. The couple couldn’t find the stitchers they needed in Maine – those who previously worked in the mills had retired or moved away. So the Waxmans set up a sewing training program. Because many of their workers were refugees from Africa and the Middle East, they found themselves teaching language and math skills as well. A white supremacist website attacked them on social media because they employed immigrants.

Time and again, the Waxmans’ core values were tested. But they persevered. Their production costs were higher, but given American Roots’ commitment to American products and treating workers fairly, they found that unions were a reliable source of business. Slowly their company stabilized and began to grow. And then the pandemic arrived and global forces threatened to sink their fragile business.

Readers of this engaging story will find themselves rooting for the plucky couple, and there can be no doubt that the success of American Roots is attributable to the energy of its founders. In that sense, it’s an uplifting Horatio Alger story.

Still, Slade notes that “there are significant caveats to Ben and Whitney’s success.” For American Roots to thrive, its customers must be willing to spend more for an American-made product. “Their hoodies may cost a little more,” one customer tells Slade, “but we’d rather support working families.” But in this era of online choices, it’s not clear that enough consumers would be willing, or able, to spend more.

There is no doubt that having a greater number of purpose-driven companies like American Roots would be a good thing. Sadly, Slade reminds us, there’s little evidence that American shoppers care that much.