First Black presidential candidate: How Shirley Chisholm paved the way

Loading...

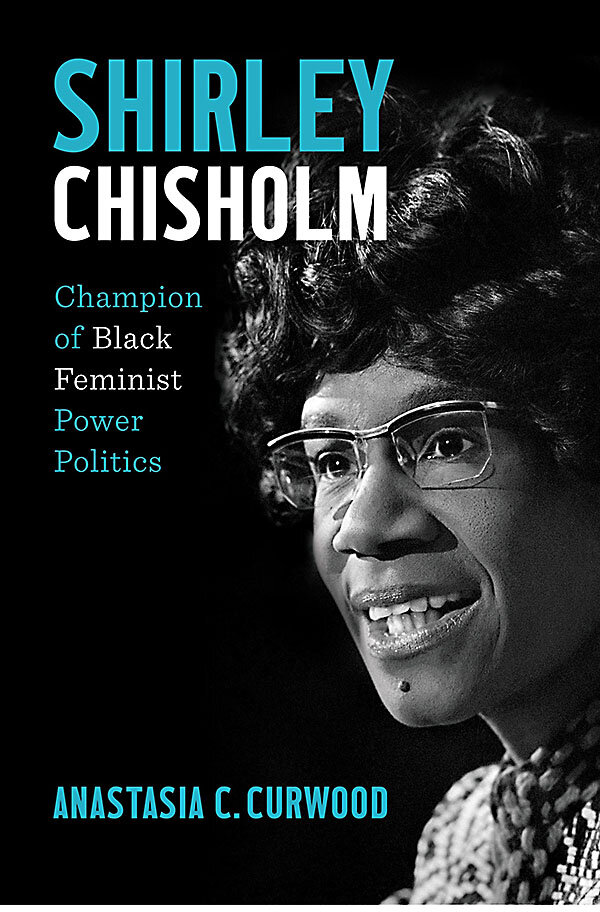

When Shirley Chisholm ran for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1968, she was not nearly as well known as her opponent, civil rights leader James Farmer. In the compelling new biography “Shirley Chisholm: Champion of Black Feminist Power Politics,” Anastasia C. Curwood observes that the novelty of a female congressional candidate was reflected in the headline of a New York Times article about the Brooklyn contest: “Farmer and Woman in Lively Bedford-Stuyvesant Race.”

Chisholm, who had long been politically active in her district and had served a term in the New York State Assembly, was more familiar to her constituents than to the Times. She won the election handily, becoming the first Black woman elected to Congress. She is remembered most for another historic milestone, however: her 1972 bid for the presidency, which made her the first Black candidate for a major party presidential nomination and the first woman to run for the Democratic Party nomination. (Republican Margaret Chase Smith became the first female candidate for a major party nomination in 1964.)

Curwood, a history professor at the University of Kentucky, offers a thorough analysis of Chisholm’s seven terms in Congress and her presidential run. As this is the first comprehensive biography of the politician, the author also covers the early years of the woman she calls a “brilliant strategist, inventive intellectual, and flawed human.” (Feminist author Susan Brownmiller wrote a biography of Chisholm for young readers in 1970, and Chisholm herself authored two memoirs, which Curwood notes “contain gaps and inaccuracies.”)

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onWhen Shirley Chisholm became the first Black congresswoman, and later, the first Black candidate to make a bid for the presidency, she paved the way for generations of Black Americans in politics.

Chisholm was born in the New York borough of Brooklyn in 1924 to a Barbadian mother and Guyanese father, and she spent six years of her childhood with her grandmother on the Caribbean island before returning to her father and mother in New York City. The eldest of four girls, she thrived under the strict, British-style education she received in Barbados and was opinionated and sure of herself from a young age. Her father encouraged young Shirley’s feistiness, but her mother subscribed to traditional gender roles and in later years didn’t support Chisholm’s political ambitions. After her father’s 1960 death, Chisholm was estranged from most of her family.

Chisholm frequently referred to herself as “unbought and unbossed” for going around New York’s Democratic party machine and its patronage system when she decided to seek office. (The phrase became the title of her first memoir.) According to Curwood, she entered politics because she felt that many residents of her Brooklyn neighborhood, specifically those who were Black, Latino, or poor, were largely ignored by local politicians. Unlike most politicians of the time, she appealed directly to women for votes.

The book can be overly detailed when it comes to its subject’s relationships with political allies and adversaries in New York. Its most stirring chapters cover Chisholm’s run for the presidency, which made her a national figure. The author summarizes the candidacy as “an attempt to win that acknowledged the impossibility of winning.” Chisholm, whom Curwood describes as “ruthlessly pragmatic,” campaigned in states that awarded delegates on a proportional basis. Her hope was to win enough delegates to influence the drafting of the Democratic Party platform and to pressure the eventual nominee, George McGovern, to select a Black running mate and to promise to appoint a woman as secretary of health, education, and welfare and a Native American as secretary of the interior.

By these measures, she was unsuccessful. While her campaign generated excitement – particularly among young people who backed her because of her strong opposition to the Vietnam War – she ultimately won only 2.7% of the vote during primary season, insufficient to exert any real clout at the Miami Beach, Florida, convention.

In the process, too, she angered many Black male leaders, particularly her colleagues in the Congressional Black Caucus, who resented that she’d decided to run unilaterally and hadn’t consulted them first. Chisholm had often, in Curwood’s words, “asserted unequivocally that she had experienced more obstacles related to sexism than to racism in her career.” But her relationships with the women’s movement were also fraught. She was bitterly disappointed when white feminist leaders like Betty Friedan and Congresswoman Bella Abzug didn’t formally endorse her presidential bid.

Still, Chisholm succeeded in her broader goal of demonstrating that anyone could run for president and paving the way for future women and minority candidates.

Curwood has a personal connection to her subject. Her mother volunteered for Chisholm’s presidential campaign, while her father, a journalist, covered it. The book includes a charming photograph of her parents laughing with the candidate in a hotel room on the campaign trail. The author clearly admires Chisholm. She credits her with a prescient understanding of the need to form coalitions to fight racism and sexism, writing that Chisholm “was practicing intersectionality” before the term was coined. But she acknowledges that Chisholm could be self-aggrandizing and opportunistic.

In the end, Chisholm emerges as a complex figure whose significance is more symbolic than tied to any legislative accomplishment. Her most noteworthy achievement in Congress was her role in crafting legislation that increased the minimum wage and included agricultural and domestic workers in its protections. President Richard Nixon reluctantly signed the bill in 1974.

Of course, symbols have power. Chisholm died in 2005 at age 80. Ten years later, President Barack Obama awarded her a posthumous Presidential Medal of Freedom, saying, “Shirley Chisholm’s example transcends her life.”