Wunderkind British explorer’s life demonstrates ice-hard resolve

Loading...

In March 1931, a young Englishman sat alone, buried alive inside a tiny makeshift weather station under nearly 10 feet of snow, at the very center of Greenland’s massive ice cap. For Augustine Courtauld, whose wealthy family had financed the expedition, food was running out. His fellow crew members, led by wunderkind explorer Henry “Gino” Watkins, were two months late in retrieving him.

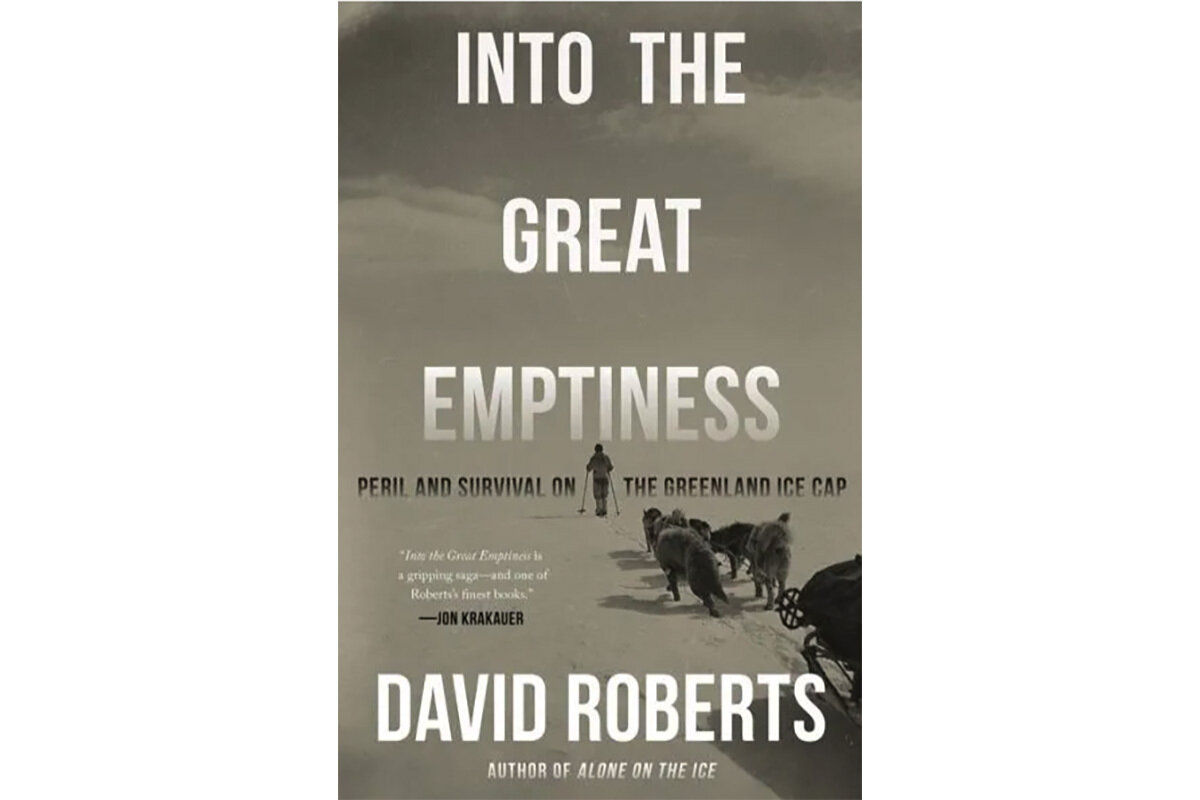

“Into the Great Emptiness: Peril and Survival on the Greenland Ice Cap” by David Roberts is both a biography of Watkins and an account of his year-long expedition to Greenland. Roberts admits that his subject was a bit of an enigma. Even men who had spent months alone with Watkins in the wilderness described him as a person who “always dwelt apart somehow, and underneath was as cold and unemotional as ice.”

In 1926, Watkins, a “feckless student, flamboyant climber and skier, thrill-seeker, lover of dancing, jazz, and parties” was suddenly transformed after attending a lecture by Raymond Priestley, the famed Antarctic explorer who’d been with both Ernest Shackleton and Robert Falcon Scott on the southernmost continent. That lecture gave Watkins his calling in life, and, coincidentally, offered him a golden opportunity: a spot on the crew of an expedition to the east coast of Greenland. Unfortunately, the expedition fell through, but as Roberts writes, “At age twenty, with no expedition experience of his own more daring than a couple of trips to tourist-thronged Chamonix, almost any budding explorer would have bitten his knuckles and accepted fate. Gino chose a different course. ... He would lead an expedition of his own.” So Watkins went to Svalbard, a Norwegian archipelago in the Arctic Sea.

That such a young man could put together crew members and raise money from private sources was one thing, but most amazing was, Roberts writes, “how ... a twenty-year-old on his first expedition [could] mold the efforts of eight companions, all older than himself ... into a coherent team.” On Svalbard, Watkins’ group discovered its center was “not sheathed in uniform ice cap, but rather in patches and lobes of thick ice interspersed with small open basins,” a geographical oddity, noteworthy even to this day. The expedition was a grand success.

Next, he was commissioned to map the new border between Quebec and Labrador, the subject of dispute between Canada and Britain. It was a difficult expedition, full of peril, but he managed to survive. While many men would have been discouraged by such a dangerous adventure, it proved to be the training ground for Watkins’ magnum opus – Greenland.

Financially supported by the Courtauld family (whose son would need to be rescued from the weather station), the British Arctic Air Route Expedition was created to establish a year-round weather station on the Greenland ice cap to evaluate the possibility of a future air route. Over the course of a year, the BAARE crew took turns manning the weather station, while investigating and mapping the interior of the world’s largest island.

Roberts writes in a smooth narrative style, peppered with white-knuckle zones. We follow the dauntless men as they plow – without the aid of radio communication – through blizzards and around crevasses, navigating calving glaciers, fighting off polar bears, hunting seals, living with Indigenous people, and, yes, getting buried alive under snow. Roberts is at times critical of Watkins’ and the crew’s lack of cultural sensitivity, which exists alongside their admiration for Native hunting skills and craftsmanship. Eventually, all make it back to England in one piece, but just barely.

“Into the Great Emptiness” might be misread as a tale of audacious and expensive misadventures, but there is an underlying message to it all – that leadership, combined with a little good fortune and love, can get you through, no matter the odds. This book will be a treat for those who “cherish the memory of England’s lost genius of Arctic exploration.”