When everything breaks down, what does it take to survive?

Loading...

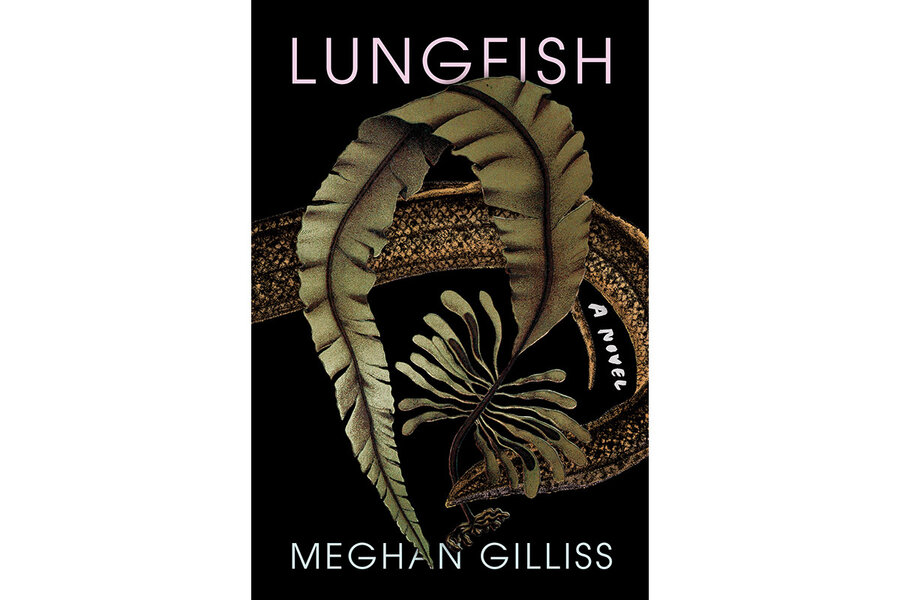

Meghan Gilliss’ debut novel “Lungfish” dramatically transports the reader to an isolated island, the wind whipping and the waves crashing as life rages. Tuck, the novel’s female protagonist, becomes symbolic of the sacrifices many women make to protect the people they love most. With grit, determination, and perpetual hope, it’s a story that hits hard and requires readers to ask themselves how much they’d give to make themselves whole.

After life begins to unravel in this piece of literary fiction, Tuck, her husband Paul, and their young daughter Agnes leave their home in Pittsburgh in exchange for an island home in Maine, left empty after Tuck’s grandmother’s death. They have no rights to the land, as it was left to Tuck’s father who has been missing for years, but with few other options, they decide it’s worth the risk to shelter there until they have a better plan.

The reader doesn’t quite understand the frigidity of Tuck and Paul’s marriage until a secret is revealed early in the novel’s 320 pages: Paul is addicted to kratom, an herbal extract that mimics opioids. He has slowly been draining the family’s finances, and the money that should have been going to food, clothing, and shelter has been feeding Paul’s addiction. And because they are not legally residing anywhere, they don’t qualify for food or housing assistance, leaving Tuck and Agnes at the mercy of whatever Paul brings home from the mainland. One of his supply runs? Graham crackers, peanut butter, instant noodles, and half a gallon of cheap milk.

To survive, Tuck takes to foraging the island, surviving on whatever she and Agnes can find: mussels, green crabs, devil’s tongue, bladder wrack, kelp, rose hips. When they spot starfish during low tide, Agnes asks, “Can I eat it, Mama?” They also discover another way of making money: selling bumper sticker-making kits found in her grandmother’s attic. Tuck’s creativity propels the story forward as their dire situation mounts.

Gillis’ writing is visceral and even harsh. Tuck’s own internal thought process flows into the short conversations she has with other characters, to the point where the reader is sometimes unsure of whether she’s talking to another character or retreating into her own unraveling thoughts. While attempting to keep herself, Agnes, and Paul alive, she also relives her own past and remembers how her parents both abandoned her, in different ways.

We learn that the island itself was a sanctuary in Tuck's youth, with her grandmother teaching her which plants were edible and how to fish. The woman was a calming presence in Tuck's tumultuous family life. The island, bleak and unforgiving as it may be, is also what sustains her and her daughter Agnes, her grandmother’s namesake. It’s a modern example of naturalism at its finest, where one can see nature as a force to survive as well as the source of our very survival.

The book is gripping, descriptive, and full of poignant revelations of both the rawness of nature and of humanity. Tuck herself is a force, an embodiment of the ebb and flow of life. At times she is fully consumed by her tasks; at other times she's detached in a way that causes the reader to ache with loneliness. Her resilience is palpable, and mirrors that of the island as she navigates circumstances that would break anyone. As she tries to control the fate of her family in the midst of many things beyond her control, the reader never really knows if she’ll make it out alive. Until the final pages, it is unclear whether or not she can weather the storm. It’s riveting.