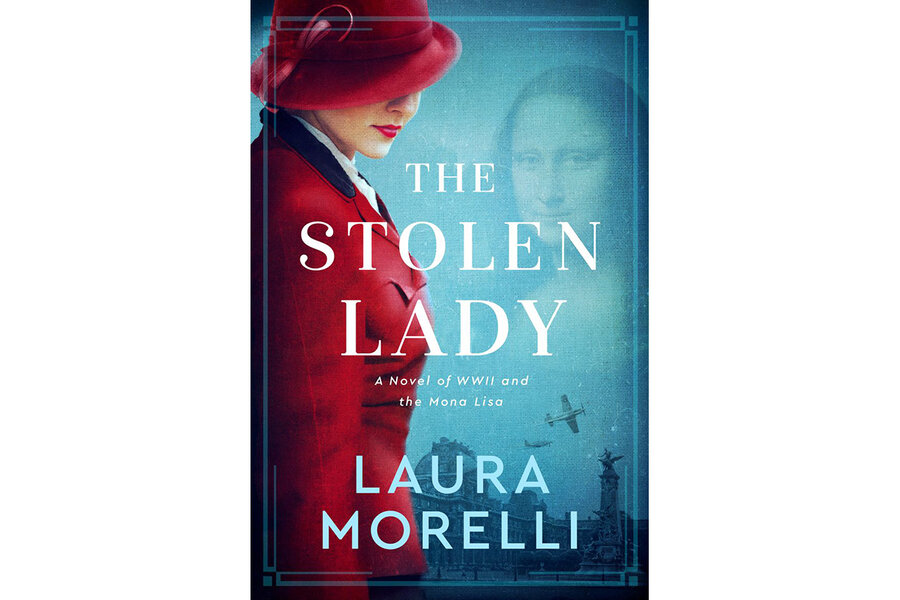

‘The Stolen Lady’ imagines how the ‘Mona Lisa’ came to France

Loading...

Today, the most celebrated Florentine lady in the world sits protected behind bulletproof glass in a temperature-controlled room in the palatial Louvre Museum in Paris. She receives countless love letters and flowers, which arrive in her very own mailbox. Leonardo da Vinci’s portrait, best known as the “Mona Lisa,” is so universally popular that the French government, which owns the painting, would be unlikely to ever sell it. How did this “icon, an embodiment of ideal beauty, a symbol of the Italian Renaissance itself,” as author and art historian Laura Morelli describes it, end up in Paris?

Morelli found refuge during the pandemic in part by imagining the saga behind the famous painting, in her novel, “The Stolen Lady: A Novel of World War II and the Mona Lisa.” Her exciting dual storylines span political upheaval from the Italian Renaissance to World War II-era France. Morelli’s love for art, history, and character bubbles over on each page as she brings da Vinci, his reluctant muse, and many other historically significant people to vibrant life. Most praiseworthy are two courageous women, 500 years apart, who risked their lives to protect the lady with the enigmatic smile from harm.

Morelli’s prose is lush and cinematic, capturing even small details, such as the secret to Lisa’s “favorite skin treatment, a concoction of snail water and donkey milk, distilled in the sun for several days, to calm and moisturize reddened skin.” The price of beauty, indeed.

Da Vinci entertainingly voices his own chapters. He’s a bit of a whiner, yet you love him all the more, as he stumbles his way through the late 15th century. He is depicted as a genius who scatters his fire, dabbling not only in art, but in a diverse array of engineering and scientific projects. His tendency to procrastinate, even when faced with a major commission such as the portrait of Lisa Gherardini, wife of Florentine cloth merchant Francesco del Giocondo, makes it all the more incredible that the painting got made in the first place. Da Vinci finds a connection with the sometimes melancholy Lisa that gives the painting even more resonance. Morelli also points out Da Vinci’s competitive nature, which is revealed in a humorous scene where an adoring public fawns over Michelangelo’s “David” sculpture.

Flash forward to 1939 Paris, where an archivist’s assistant, Anne Guichard, watches as the Louvre’s employees pack up crates of countless artworks to be sent on trucks and hidden away at Chambord Castle and other locations in the French countryside. A dangerous hide-and-seek game ensues with the Nazi treasure seekers. Anne draws strength and courage from her resolute colleagues, and also intensifies her commitment to the Resistance.

Switching back to Renaissance Italy, we encounter the story of Bellina Sardi, a servant who has cared for Lisa since she was a baby. Bellina follows her mistress into the del Giocondo household after Lisa’s marriage, and Bellina’s loyalties are tested as she falls under the spell of a charismatic monk named Savonarola. The monk has his own schemes, as he and his insurgents are bent on destroying the property of wealthy families and defying Medici rule. Bellina’s struggles to define her life purpose are heartwarming, and her devotion to hiding da Vinci’s portrait of her mistress is affecting. (While the character of Bellina is entirely fictional, the del Giocondo family is drawn from basic outlines of the actual historical individuals.)

The novel bursts with not only suspense and intrigue, but also with friendship and even romance. It’s far more than a book about the importance of preserving great works of art in times of darkness. Morelli hits all the right notes as she draws on history to illuminate two different, but parallel, eras in which so much more than art was at stake.