‘The Farmer’s Lawyer’ tells a David and Goliath legal story

Loading...

Attorney Sarah Vogel had never argued – or even attended – a trial before she pursued the case of a lifetime in the early 1980s on behalf of struggling North Dakota farmers facing foreclosure.

In the process, Vogel took on $50,000 in personal debt, lost her house, and had to move with her young son into her parents’ basement.

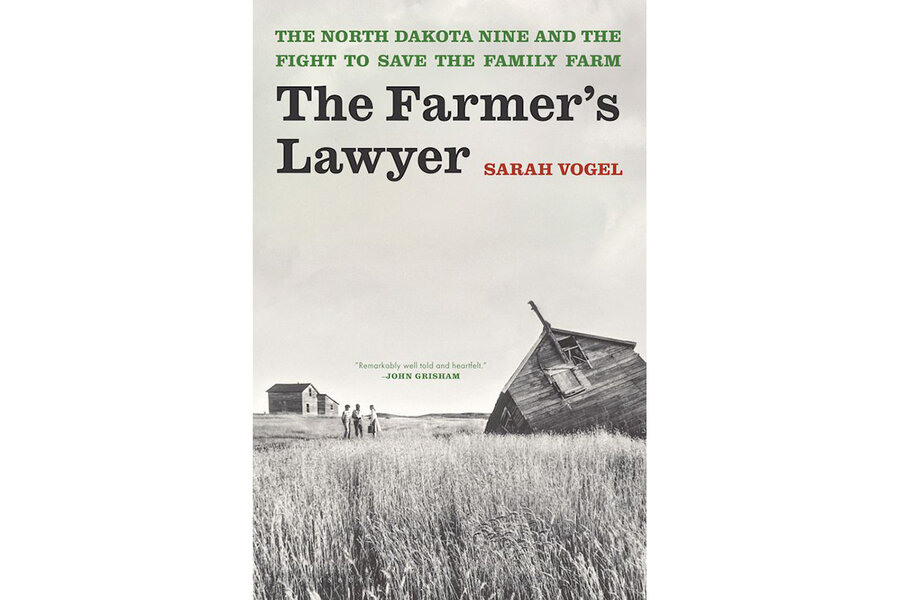

Vogel tells the remarkable story of her improbable legal victory against the federal government in her new book “The Farmer’s Lawyer: The North Dakota Nine and the Fight to Save the Family Farm.”

She’s not an entirely unlikely heroine in what she describes as “a David and Goliath fight if ever there was one.” Vogel has deep roots in North Dakota, and the impulse to help farmers, along with the instincts of a legal mind, runs in the family.

Vogel’s grandfather served as a top adviser to Governor William “Wild Bill” Langer, who called out the National Guard to prevent farm foreclosure sales during the Great Depression. President Dwight D. Eisenhower appointed her father the state’s U.S. attorney.

Vogel had moved east to see if she could succeed where her name had no cachet. By 1980, she was a divorced mother with a toddler son working as a Treasury Department lawyer in Washington.

That’s when a farmer back home asked for help battling the Farmers Home Administration, a now-defunct component of the Department of Agriculture known as FmHA, which provided loans to farmers who couldn’t qualify for credit from private lenders.

The prosperous early 1970s – when farmers sold massive quantities of grain to the Soviet Union – had already given way to hard times as prices fell and international competition increased. The newly elected Reagan administration compounded farmers’ troubles with a policy decision designed to cut government spending and reduce the federal deficit.

Facing pressure to reduce delinquencies, FmHA began demanding struggling farmers pay up in full or face foreclosure. That policy shift “triggered the ‘80s farm crisis in the same way the stock market crash in 1929 triggered the Great Depression,” Vogel writes. “It threw oil on a fire that was already burning.” Vogel quit her secure Washington job and moved back home to North Dakota, thinking she’d find work at a law firm there. Instead, the farmers’ cause consumed her life for years.

Distressed farmers found their way to Vogel by word of mouth. She ultimately filed a class action lawsuit with nine named plaintiffs representing 8,400 North Dakota family farmers, arguing the FmHA didn’t provide them with adequate due process.

Anyone seeking a dispassionate history of the case should look elsewhere. This is an advocate’s tale of fighting callous bureaucrats and cold-hearted prosecutors, while struggling to keep the lights on in her own home.

Representing clients who could only afford, in one instance, to compensate her with some frozen fish and homegrown produce worsened her own abysmal financial situation. Her work phone got disconnected, she was locked out of her office for unpaid rent, and only fears of tarring her family’s good name kept her from filing for bankruptcy.

Still, Vogel had some advantages. Her father offered refuge in his law firm and sagely recommended she file suit before a particularly sympathetic federal judge.

She enlisted the help of two well-placed out-of-state lawyers: The ACLU’s national legal director Burt Neuborne, who was looking for a way to advance the cause of economic justice and Allan Kanner, a class action wizard whose father operated a south Jersey chicken farm. They helped her expand the class action to include farmers beyond North Dakota.

The Justice Department likewise enlisted some high-wattage help in the form of ex-Supreme Court Justice Arthur Goldberg. He did little to advance the government’s cause as Vogel ultimately won an injunction on behalf of 240,000 FmHA borrowers nationwide.

Vogel, however, does credit Goldberg with helping her accomplish one thing: a payday. The former justice didn’t file a challenge to her fee award on time, and the court wouldn’t grant an extension. She gave her father the $101,837 in attorneys’ fees she’d earned to reimburse him for his firm’s support.

Vogel went on to serve as North Dakota’s agriculture commissioner, the first woman elected to the office in any state. This book is a testament to what was an even greater achievement.

Seth Stern is the author of a forthcoming Rutgers University Press book on Holocaust survivors who settled as poultry farmers in southern New Jersey.