Jewish women spied, smuggled, and sabotaged under the Nazis’ noses

Loading...

In 1942, two years before his death at the hands of the Gestapo, Polish-Jewish historian Emanuel Ringelblum, in a diary entry written from the Warsaw Ghetto, praised the courage of female resistance fighters. “How many times have they looked death in the eyes? How many times have they been arrested and searched?” he marveled. “The story of the Jewish woman will be a glorious page in the history of Jewry during the present war.”

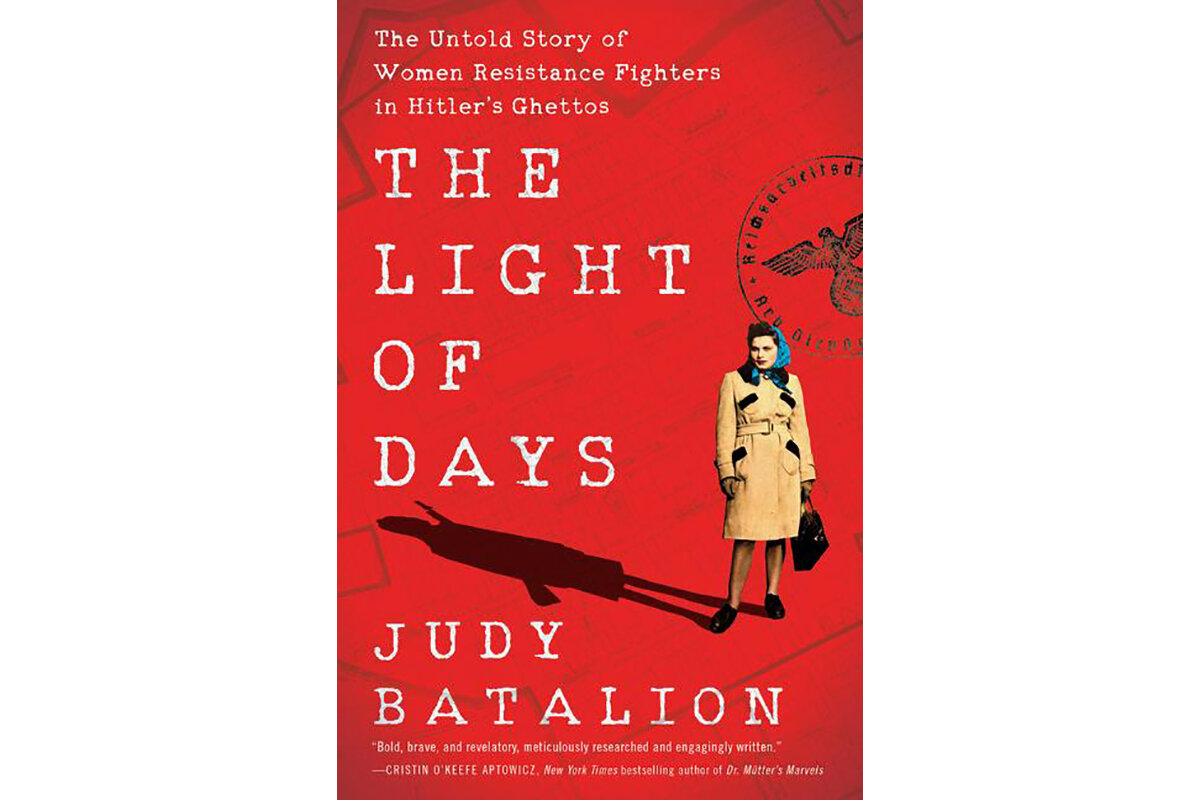

Alas, Ringelblum’s prediction did not come to pass. Instead, as Judy Batalion observes in her thrilling, devastating new book, “The Light of Days: The Untold Story of Women Resistance Fighters in Hitler’s Ghettos,” the heroism of the female resisters has been largely forgotten.

Batalion embarked on the project after coming across a neglected Yiddish volume in the British Library called “Women in the Ghettos,” published in 1946. The stories of young women “smuggling, gathering intelligence, committing sabotage, and engaging in combat” astounded her, not least because the author, whose grandparents were Polish Jews who fled the Nazis, had grown up thinking of escape as the only means of resistance available to Europe's Jews during the Holocaust.

Why We Wrote This

As more is learned about women in history, untold stories of courage and heroism emerge. These revelations challenge how women have been perceived, and cast them in a fuller light.

The successes of the Jewish resistance were minor relative to the scale of the Nazi genocide. (More than 90% of Poland’s Jewish population perished in the Holocaust.) Even so, reading about the intricate underground web of fighters and spies is revelatory. “The Light of Days” traces the experiences of roughly 20 Polish women, based on their own memoirs and testimony, archival material and other historical sources, and interviews with the family members of those who survived the war. In Batalion’s hands, their stories are taut and suspenseful, but the author also weaves in important context about prewar Poland, life in the ghettos, and the progression of the war.

Many resistance fighters, both female and male, came from a robust network of Jewish youth groups, often with Zionist and socialist leanings, that had been active before Germany invaded Poland in 1939. They remained operational at the start of the war, as the Germans isolated Poland’s Jewish population in hundreds of ghettos. They secretly created and distributed books on Jewish history and culture (books by Jewish authors had been banned) and taught classes to ghetto children. “They were preparing for a future they still believed in,” Batalion writes.

Once they came to the sickening realization that the Nazi plan was the liquidation of the ghettos and the annihilation of all Jews, the youth groups shifted to armed defense, amassing weapons, real and makeshift, and training members to fight. (Some joined the partisan units in the forests.) They were not unrealistic about what they could achieve; the goals of acts of resistance like the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising were to exact some small revenge and to die with honor.

Batalion explains why women were tasked with the dangerous work of sneaking into and out of the ghettos, passing along intelligence, cash, and supplies: unlike Jewish boys, who had often studied in yeshivas, girls had attended public schools and thus spoke Polish without a recognizably Yiddish accent. More importantly, a male’s Judaism could be easily confirmed by seeing if he was circumcised. Jewish women with Aryan features had a better chance of safely traveling throughout Poland, although their risks were still enormous. A woman with a pistol hidden in a loaf of bread might be recognized as Jewish by a former neighbor, or her documents might be discovered to be forgeries.

Most of the female resisters were in their teens and early 20s; most had already lost their families, and they formed intense bonds with their comrades. The teenaged Renia Kukielka, who wrote a detailed memoir right after the war, is one of the book’s central figures. Described by Batalion as “a savvy, middle-class girl who happened to find herself in a sudden and unrelenting nightmare,” Renia followed her sister into the resistance after their parents were killed.

Renia smuggled weapons and cash and helped sneak Jews into hiding places. Her feats of bravery included jumping off a moving train and proceeding through Nazi checkpoints with fake passports and weapons strapped to her body. She was eventually imprisoned for traveling with a forged passport. Although she was starved and beaten brutally, she would have been killed had her captors known she was Jewish. Renia escaped the prison. Soon after, she was smuggled out of Poland and eventually reached Palestine. Her story is so remarkable, Batalion reports, that “in her sixties, Renia read her own book in disbelief: How had she possibly done those things?”

Batalion offers many reasons for the erasure of these women’s stories. For one, most did not live to tell of their experiences. Batalion further argues that scholars haven’t highlighted memoirs like Renia’s because “writing about fighters might give the impression that the Holocaust was ‘not that bad’ – a risk in a context where the genocide is fading from memory.” In addition, the author adds, the focus on resistance could lead to “judging those who did not take up arms, and ultimately blaming the victim.” Mindful of these hazards, Batalion has produced an overdue account that helps restore some of the young Polish victims of the Holocaust to their full complexity.