Extinction isn’t inevitable. ‘Beloved Beasts’ explains why.

Loading...

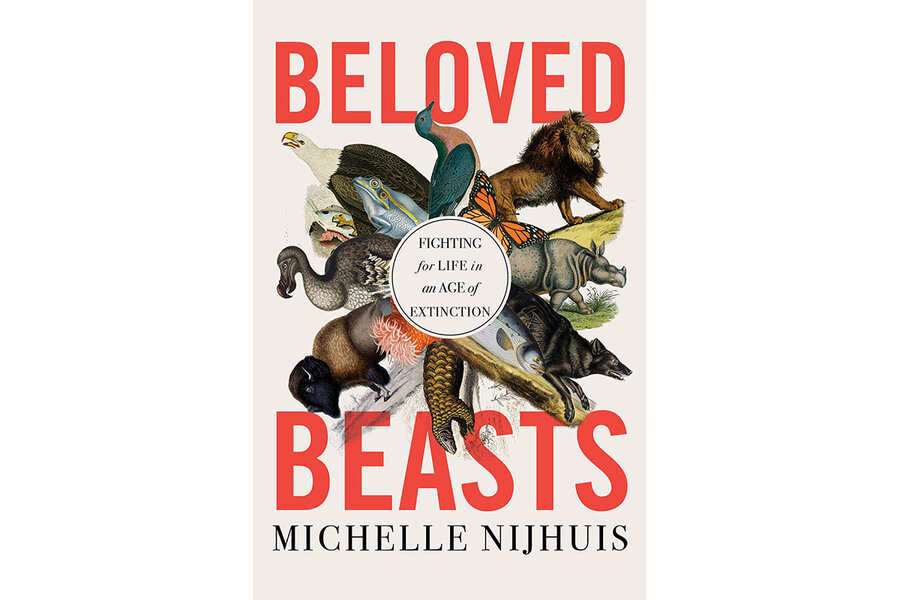

Without the efforts of conservationists, the world would have no bald eagles, black rhinos, or whooping cranes. But it’s not enough any longer to focus on saving individual species, writes Michelle Nijhuis in her new history of conservation, “Beloved Beasts: Fighting for Life in an Age of Extinction.” With an estimated 1 million species threatened with extinction, society cannot afford to view animals – including humans – in isolation.

Instead, Nijhuis explains that the cutting edge of conservation biology prioritizes connectivity. “To dismiss our complexity, our ability to be both constructive and destructive, is to give up on the whole project of species conservation and, indeed, on the human project itself,” she writes.

A lively, mostly chronological history of ideas extending from 18th-century botanist and taxonomist Carl Linnaeus to modern-

day biochemist Jennifer Doudna, “Beloved Beasts” spotlights a variety of conservationists, environmentalists, and ecologists. Figures both famous (Rachel Carson and Theodore Roosevelt) and less widely known (Rosalie Edge and Julian Huxley) offer sometimes conflicting opinions of how best to treat animals on the verge of vanishing.

Nijhuis devotes a chapter to the forester, wildlife manager, and author Aldo Leopold, who originally advocated for wolf extermination but made an about-face after witnessing the sad results of deer overpopulation. She also highlights the work of Carson and writes about the publication of her seminal 1962 book, “Silent Spring,” which eventually led to the banning of the pesticide DDT and the rehabilitation of the bald eagle.

What “Beloved Beasts” also makes clear is that agreement even between like-minded individuals is difficult. For example, when contemporary conservationists from the West arrive in Africa, their actions to save animals can come at a high cost to local farmers. Nijhuis acknowledges that “in many cases – and all parts of the world – the poor carry the burdens of conservation, while the wealthy enjoy most of the ecosystem services.” She writes about Garth Owen-Smith, a South African pioneer of community-based conservancy who has worked with the Namibia Wildlife Trust to protect big-game animals from poachers in a way that includes local expertise and values.

In reviewing conservation’s advances and missteps, Nijhuis argues that the mission of such efforts must be “the protection of biological diversity, ecological complexity, and the evolutionary process – in short, the preservation of possibility.”

“Beloved Beasts” is not didactic, but it’s still a call to action. And it has compassionate advice for readers who yearn for resilience amid the pandemic and the climate crisis.

“The past accomplishments of conservation were not inevitable,” Nijhuis argues, “and neither are its predicted failures. We can move forward by understanding the story of struggle and survival we already have – and seeing the possibilities in what remains to be written.”

With urgency, passion, and wit, Nijhuis recognizes those possibilities clearly and writes both to preserve history and predict what may lie ahead. “The great challenge of conservation is to sustain complexity, in its many forms, and by doing so protect the possibility of a future for all life on earth. And for that,” Nijhuis warns, “there are no panaceas.”

Alternately heartbreaking and encouraging, “Beloved Beasts” proposes a larger vision of stewardship – one that extends beyond just winsome or majestic creatures to encompass the entire planet.