An early Black mutual aid society surfaces in New Orleans

Loading...

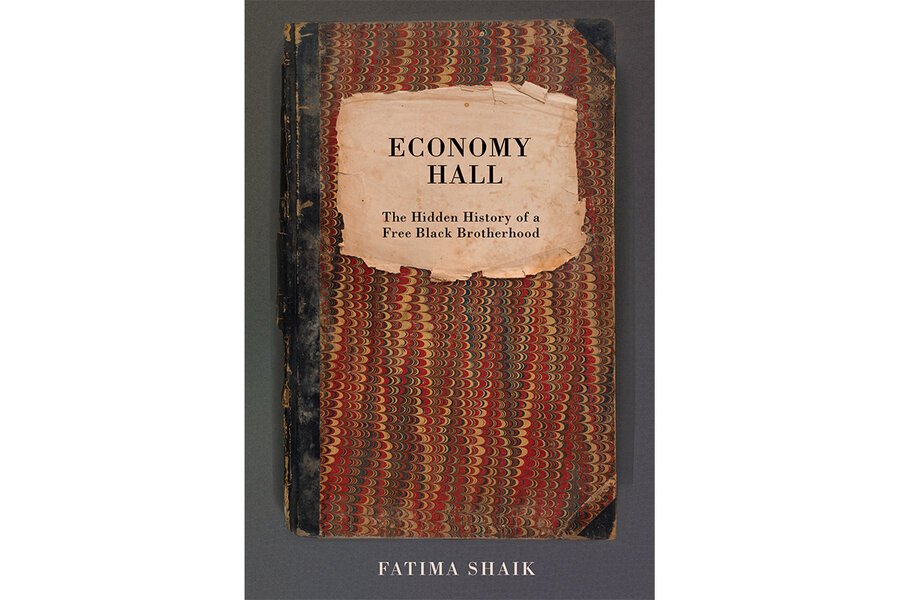

Long before Fatima Shaik set out to tell the story of the Société d’Economie et d’Assistance Mutuelle (the Economy and Mutual Aid Association) of New Orleans, the group’s records were nearly lost. In the 1950s, when Shaik was a child, her father salvaged a collection of ledgers destined for the dump. Full of elegant French script, the books dated back to 1836 and contained the history of a Black mutual aid society formed before the Civil War.

The ledgers sat for decades in Shaik’s family home where she rediscovered them as an adult. “I realized that not only were these books old, but they told a story about America that few people alive had heard.”

In “Economy Hall: The Hidden History of a Free Black Brotherhood,” Shaik provides a portrait of Black American life that stretches from the Haitian Revolution to the golden age of jazz. At the story’s center is one of the society’s longtime secretaries, Ludger Boguille.

Shaik’s focus on Boguille is intriguing, as he is not a high-profile historical figure. While Black abolitionists like David Walker advocated for people of color to revolt, Boguille held his peace; after all, his parents were slave owners. But his complicated background speaks to the city’s complex social order.

Born in 1812, Boguille grew up in New Orleans and belonged to a privileged community of free people of color. When he was a young man, the growth of the nation’s economy was tied to New Orleans, where cotton, sugar, and rice passed through its port, along with enslaved people. While the city prospered, its success was built on “a tragic foundation,” Shaik writes.

In 1846, after familial loss and hardship, Boguille became involved with Economie. Representing a wide variety of skilled professionals from shoemakers to international brokers, the society collected dues to pay for medical and burial expenses. It also held fundraisers and banquets attended by the city’s elite people of color.

Shaik painstakingly recounts Economie meetings, translating the society’s minutes from the original French. While the author’s fidelity to her primary source material is commendable, it does result in some passages being overloaded with specifics that feel insignificant relative to the book’s larger narrative arc. Ultimately Shaik is most successful when placing the Economie’s chronology within a broader context.

The society managed to flourish even while tensions over slavery ramped up. Louisiana seceded from the Union in 1861; Boguille – a Southern Black man married to a white woman from the North – joined the Confederacy, albeit for a short period of time. In 1866, he bore witness to the Mechanics’ Institute massacre, one of the Reconstruction Era’s most violent events.

While considerable steps were taken toward racial equality following the Civil War, the Jim Crow era reversed this progress. During the last years of Boguille’s life, New Orleans grew increasingly segregated and acts of white terrorism made life extremely difficult for the city’s Black residents. Boguille died in 1892. As Shaik writes, “He had lived as a rational man in a nation with an irrational measure – race.” Shaik’s narrative extends well past Boguille’s death – as society changed, so too did the Economie, which played a supporting role in the evolution of jazz. In its final days, Economy Hall, the group’s headquarters, became an indispensable part of the city’s cultural legacy.