Forced into camps, Japanese Americans found respite in football

Loading...

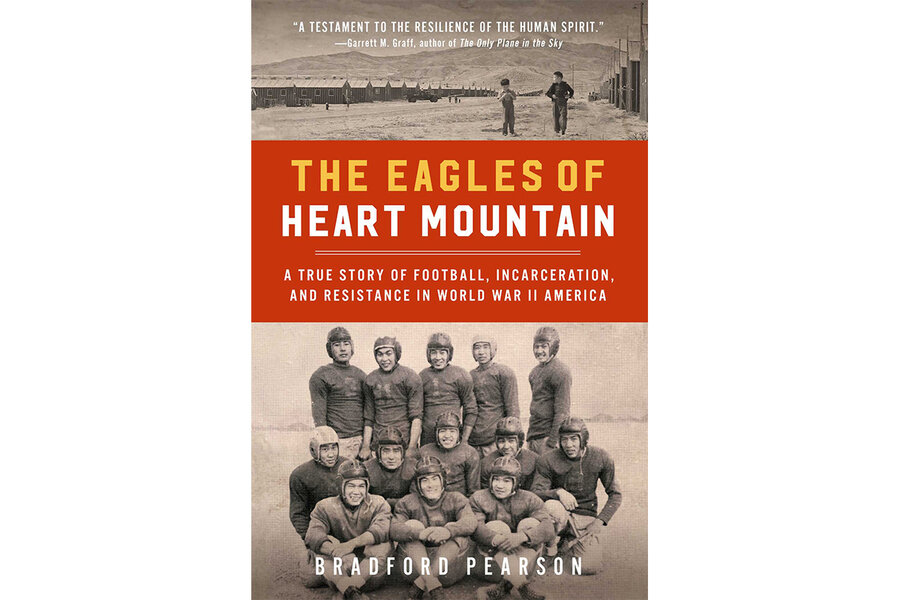

The football team wore white and gold, athletic tape held up their pants, and cardboard covered their legs instead of thigh pads. They were not outfitted for victory, but then again, they were playing inside a concentration camp. In “The Eagles of Heart Mountain: A True Story of Football, Incarceration, and Resistance in World War II America,” Bradford Pearson tells the history of the imprisonment of 120,000 Japanese-American people beginning in 1942.

The period of confinement for Japanese American citizens has known different names in the 80 years since Executive Order 9066 – which gave military commanders the authority to remove persons of Japanese ancestry from their West Coast homes – was signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Words like “internment” and “relocation” have been employed to describe this mass removal with distinctly racial motivations, but Pearson uses “incarceration” in line with the recommendations of the nonprofit historical organization Densho.

Japanese immigrants and their American children were already regarded with racist suspicion in the years leading up to the war. But in the wake of the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service, those tensions bubbled over into outright hostility. Unfounded fears of Japanese American citizens taking up arms for Japan, though many were second- or third-generation Americans, were used to justify their removal. No such order was levied against Italian Americans or German Americans.

The camps to which Japanese American people were sent during the war years were constructed on government lands that were unsuitable for farming – areas that were “passed over by even the most desperate of pioneers.” Heart Mountain in Wyoming, just north of Cody, was one such place. Brutal summers and winters, intense winds, and rattlesnakes made life difficult for the inhabitants of Heart Mountain Relocation Center, but residents did their best to live normal lives, including playing good old American football.

Without much time to do so, residents threw together a high school team: the Heart Mountain Eagles. Only a few of the team members had football experience, and the rest had less than two weeks to learn ahead of their first game. Yet their determination and sheer speed – not to mention the natural talent of quarterback Tamotsu “Babe” Nomura – helped the scrappy team achieve victory. They eventually became red hot and won nearly every game they could arrange; a few teams from nearby high schools even declined to face them, likely afraid of a rout.

Although the Heart Mountain Eagles are at the figurative center of this book, sports fans seeking football history will find themselves searching for even the mention of a ball within the first half. Contrary to what the title implies, the football team is a secondary focus. However, when the sports writing does pop up, it is nothing short of glorious.

“Arms pumping as the dust kicked up beneath him, he was gone. Gone from that field, gone from camp, gone from Wyoming.” writes Pearson, describing a play by Nomura. “Replace all the bad with all the good and for those seconds he can be just a boy doing what he loves most.”

Using meticulous research and a whole lot of heart, Pearson gives a devastatingly powerful history of Japanese American internment and demonstrates its absurdity with the tale of an undeniably all-American football team. These young men were the epitome of what it means to be an American: They were hard-working children of immigrants, pushing themselves to be the best they could be for themselves and their families. The fact that they named their team after that most American symbol – the eagle – is the period at the end of the sentence. Though there is not as much football as the title seems to promise, this is an inspired and necessary work of history.