Notre Dame cathedral survived fire, war, and Napoleon’s redecorating

Loading...

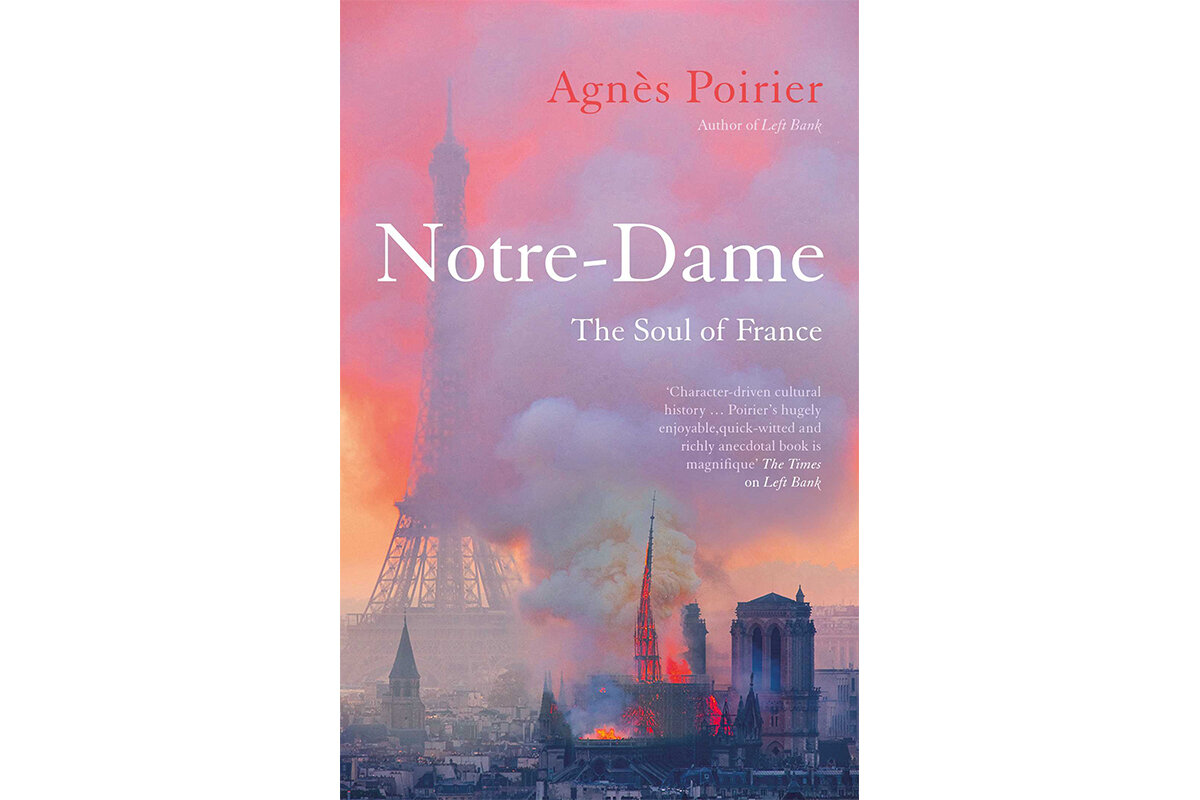

On April 15, 2019, the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris caught fire. Eyewitnesses in the streets and viewers around the world waited, shaken and silent, as the spire fell, and were on tenterhooks at the thought that its towers could be next.

Author Agnès Poirier vividly re-creates the scene in her superb history of the 800-year-old cathedral, “Notre-Dame: The Soul of France.” As the inferno raged, firefighters engaged in “hand-to-hand combat” to avoid a total collapse of the structure. They succeeded, but the fire, which occurred during restoration work, decimated the roof and damaged construction scaffolding. In June of this year, workers returned to the job of removing pieces of scaffolding, after the pandemic had halted reconstruction. President Emmanuel Macron has vowed the cathedral will reopen in 2024.

The determination to see this landmark rebuilt is testament to the regard that the French have for the cathedral. It is more than a historic building: Its history mirrors that of France. “We thought she was immortal, we thought she was made of imperishable matter, we thought she would bury Paris, she would see the end of times, long after we have all turned to ashes,” Poirier writes.

Why We Wrote This

Can a structure inspire awe and devotion? More than flying buttresses and rose windows, Notre Dame cathedral has symbolized strength and continuity, not just for Parisians but for people all over the world.

Following the harrowing summary of the fire itself, Poirier backtracks to the 1100s, sketching Paris as a city teeming with promise. The bishop of Paris, Maurice de Sully, hired an architect to prepare plans for a cathedral of rare, yet discreet, beauty. “We will never know where he came from, whether he was the son of peasants ... or a relative of Louis VII,” Poirier writes of the unknown original architect. Unnamed, too, are the bishop’s serfs, who were pressed into service as laborers.

Poirier details the cathedral’s design innovations, set in motion by the original architect and retained by his successors, including Eugène Viollet-le-Duc in the 13th century. She writes that the intent was to project a spartan, stringent grandeur. “Her serenity was almost austere.” Descriptions abound of everything from the smallest iron door fittings to the immense, airy nave.

The book is filled with a remarkable cast of historic figures. Poirier notes, for example, Napoleon’s meticulous if gaudy handiwork in making the edifice acceptable for his coronation, including the whitewashing of walls and vaults (which wrecked frescoes) and the covering of interior stone with fabrics and marble floors with carpets.

Victor Hugo is given a chapter in Poirier’s book, thanks to “The Hunchback of Notre-Dame,” which still inspires people around the world to care about the cathedral and wish to preserve it. Poirier calls Hugo’s novel “the book that keeps on looking after Notre-Dame.”

Leapfrogging from one historical epoch to another, Poirier describes how the cathedral survived the Hundred Years’ War, the French Revolution (during which time it was temporarily called the “Temple of Reason”), and World War II. Yet Poirier suggests that it endures not simply for the splendor of its design, nor for the backdrop it provided for European history, but for our common attachment to it – a deep-seated connection exemplified in the reaction to the 2019 blaze.

Despite France’s pride in its secularism, Poirier writes that the fire brought forth signs of faith: “Notre-Dame, a place where the sacred met the secular, reminded us all of where we came from in an unexpected and powerful way.”