Edward Snowden arouses little sympathy in ‘Dark Mirror’

Loading...

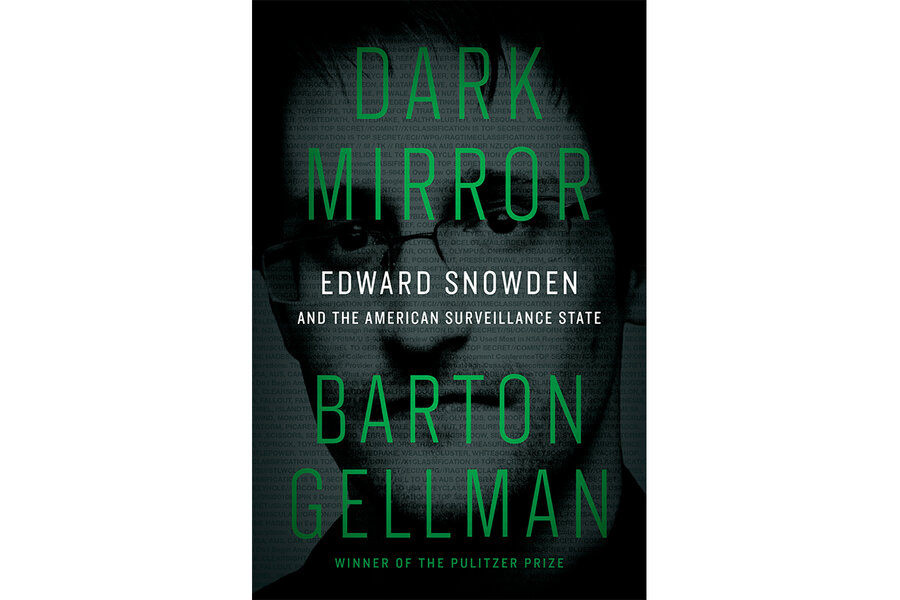

Edward Snowden’s actions have helped shape the post-9/11 world. In “Dark Mirror: Edward Snowden and the American Surveillance State,” three-time Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Barton Gellman provides an insider’s view of Snowden.

Infamously, Snowden released classified documents from the National Security Agency to journalists in 2013. While working as a subcontractor for the agency, Snowden became aware of several clandestine surveillance programs that were harvesting vast amounts of personal data and intercepting private communications among Americans without their knowledge and without a warrant. He tried to raise concerns with his superiors, but he felt like he was getting nowhere. So he stole large tranches of the records in question and fled the country.

In Hong Kong later that year, he met with journalists Glenn Greenwald (whose book on Snowden, “No Place to Hide: Edward Snowden, the NSA, and the U.S. Surveillance State,” came out in 2014), Laura Poitras (whose Academy Award-winning documentary, “Citizenfour,” came out in 2014), and Ewen MacAskill. And he began releasing some of the information he’d copied, working with former Washington Post reporter Gellman, among others, through a series of elaborate security measures involving throwaway laptops, burner cellphones, and encrypted communications.

Snowden eventually accepted asylum in Russia; that’s where he married his longtime girlfriend Lindsay Mills, where he wrote his 2019 memoir “Permanent Record,” and where he lives today. He gives speeches all over the world via teleconference, and although American government officials have previously expressed a desire to incarcerate and even assassinate Snowden, he’s become the face of contemporary concerns over unregulated government surveillance to many thousands of people.

Gellman narrates all the twist and turns of this story with a gusto worthy of John le Carré. Snowden “had chosen to risk his freedom ... but he was not resigned to life in prison or worse,” Gellman writes in a summary of the email that Snowden sent when he fled America. Snowden himself tells Gellman in their early exchanges that he was certain the U.S. government would have had him “committed” if he’d stuck around to face charges, and this reflects the almost casual contempt government officials voice for Snowden throughout the book. As former Director of National Intelligence James Clapper tells Gellman at one point, “one man’s whistleblower is another man’s spy.”

That air of menace hangs over “Dark Mirror,” mainly because Gellman himself is always mentioning it. “My reporting took place in a perilous environment,” he writes, “and I never had the luxury of forgetting that.” This contrasts sharply with Snowden’s own behavior when the two finally meet face-to-face in Moscow in 2013. “I had expected to find a man embattled and alone, in hiding, possibly full of regret for the life he had lost, disoriented by a language and culture he did not understand,” Gellman writes. Instead, Snowden appears “content.”

Although this is undoubtedly an important book in the history of the Snowden story, it’s also often an unpleasant one on a number of levels. The narrative presents precious few footholds for empathy, either for Snowden or for U.S. government officials. Right down the chain of command, the latter come across extremely poorly. For example, when James Clapper was asked in a Congressional hearing “Does the NSA collect any type of data at all on millions, or hundreds of millions, of Americans?” he responded, “No, sir. ... Not wittingly” – a statement which many observers regard as a blatant lie under oath (though Clapper has characterized it as a “clearly erroneous” statement resulting from his own misunderstanding of the question).

And Gellman inserts himself into the book to a degree that seems unnecessary. For example, he seems compelled to include remarks like those of Washington Post editor Jeff Leen, who tells him “If Bart Gellman is afraid of something, that makes me afraid.”

The Snowden of “Dark Mirror” embodies a noxious combination of arrogance and self-pity, much closer to the weaselly opportunist in Edward Jay Epstein’s 2017 book “How America Lost Its Secrets: Edward Snowden, the Man and the Theft” than to the semi-heroic figure that Gellman perhaps intended to paint, or the modern-day saint venerated by an entire generation of young people.

But Gellman’s Snowden is a truth teller nonetheless. “I’m not perfect,” he tells Gellman. “I’m flawed. I’m human. I could have made terrible mistakes. But I felt that I had an obligation to act.”