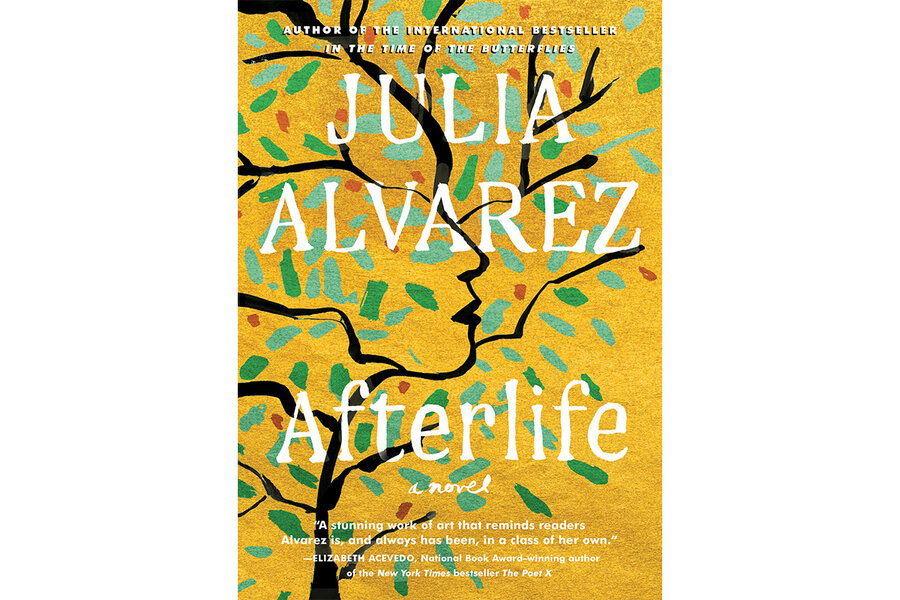

In ‘Afterlife,’ a woman forges a path through grief

Loading...

Retirement is supposed to be a time filled with family, trips, and hobbies – a finale to a long and satisfying career. This was to be the case for Antonia Vega, a recently retired college professor and writer living in Vermont. But everything changes one day when her husband Sam never shows up to a celebratory dinner.

Julia Alvarez’s newest novel “Afterlife” explores what happens when the golden years suddenly dim into something unexpected. Sam’s untimely death (this is no spoiler; the opening pages deliver this news) charts Antonia a course she’d really rather not take.

The home that Antonia and Sam built together no longer feels like a place of comfort, but instead an unsteady boat on an uncertain sea of loss. “Late afternoons as the day wanes, in bed in the middle of the night, in spite of her efforts, she finds herself at the outer edge where, in the old maps, the world drops off, and beyond is terra incognita, sea serpents, the Leviathan – HERE THERE BE DRAGONS,” writes Alvarez. “Countless times a day, and night, she pulls herself back from this edge. If not for herself, then for the others: her three sisters, a few old aunties, nieces and nephews.”

But the chaos of life has a way of interrupting periods of mourning, and this is no different for Antonia. Her three sisters think a reunion in Illinois to celebrate her upcoming birthday is just what she needs. At home, Antonia finds that now she instead of Sam must be the one to answer the problems knocking at her front door – like Mario, one of the undocumented Mexican workers who milks the cows at the farm next door. He wants her help in bringing his girlfriend – stuck in the powerful clutches of smugglers in Colorado – safely to Vermont.

The retired college professor, who once collected ideas for stories in a shoebox in her office, really doesn’t want to get involved with this scenario. And yet a reluctant empathy stirs her from her grief. She is an immigrant herself, after all; she came to the United States as a child with her family from the Dominican Republic, and she knows she is one of the few in her rural community who can help Mario navigate language barriers. But her involvement unwittingly sets off a chain of events that ties her in even more tightly.

“Afterlife” is Alvarez’s first novel in a decade, and the author skillfully brings her signature warmth and gentleness to issues that are anything but: death, immigration, and health care. Without making overt political statements, Alvarez’s poetic and meditative prose pulls back the curtain on the ambiguous nature of power dynamics and wades into the discomfort wrought by family relationships.

More subtly, Alvarez offers a study in the concept of home. What happens when it is no longer a fixed place of refuge? Who earns the right to call a place a home? Can a place of love and sharing be displaced by loss and desire?

In the midst of these upheavals, Antonia finds her resolve to forge ahead. “What lies beyond the narrow path, the nibble, the sip, where the dragons be?” Antonia wonders. “Just because she doesn’t yet know doesn’t mean she should close down and settle for the joyless default. The earth doesn’t need one more resentful, depressed sort. Having studied and taught stories and poems all her own life, it’s now in her DNA, to want to give that life a shapely form.”

In the end, all of this emotional mayhem yields a positive effect. And as the master storyteller, Alvarez collects these broken fragments of Antonia’s life to form a whole. The novella ends with Antonia learning the Japanese repair technique kintsugi (in which repairs to cracked pottery are not concealed but rather highlighted with gold) and thus Alvarez delivers a final message: In periods of loss and emptiness there is often something better – a person, an opportunity, a perspective – waiting to disrupt that space, and to give a new life after death.