He raised his son to love wild places. Then his son disappeared.

Loading...

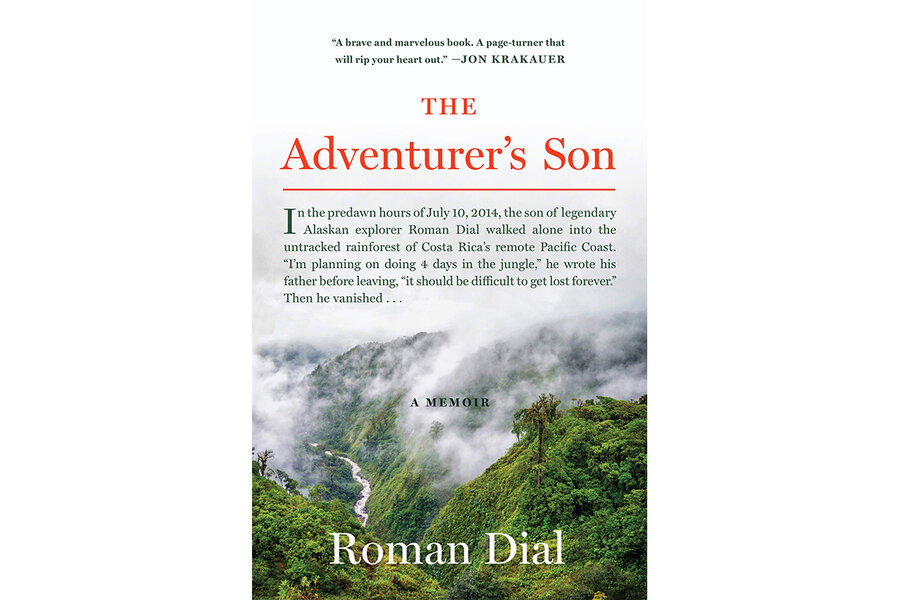

In July of 2014, the son of renowned American biologist Roman Dial disappeared into Costa Rica’s lush Corcovado National Park. Cody Roman Dial had slipped into the jungle with a light backpack and a machete, but no tourist permit. This was not atypical. He was the sort of traveler who preferred off-the-grid excursions, a way of life he had learned from his father, whose exploits in both the tropics and the Arctic were well known in the tightknit world of American adventurers and explorers.

Indeed, for the better part of a year, the younger Dial had been traveling throughout Central America, hiking alone, off-trail, through some of Mexico’s and Guatemala’s most daunting landscapes. This time, he had written his father, he planned to spend four days in the wilderness and then take a day to walk out. “I’ll be bounded by a trail to the west and the coast everywhere else, so it should be difficult to get lost forever,” he emailed his father.

That was the last Dial ever heard from his son.

What followed were years of searching and heartbreak, and ultimately the elder Dial’s reckoning with a family ethos of independence, exploration, and adventure. “The Adventurer’s Son” is Dial’s memoir of this quest – but also of a remarkable family, one that eschewed the “safe and boring” for something different; something intense, sparkling, and wild.

Within a familiar storytelling arc of mystery and man-versus-nature tension, Dial looks into the mirror and starts to ask whether an idealistic version of nature, and the explorer’s role within it, is not somehow problematic.

Dial and his wife, Peggy, raised their son and younger daughter in a way that reads like modern parental fantasy. Although based in Alaska, where Dial still works as a biology professor at Alaska Pacific University, the family lived for a time in Puerto Rico, where the children learned to catch lizards and explore coral reefs. The foursome took a monthlong, 1,500-mile road trip across Australia, and accompanied Dial as he traveled to Borneo for research. When Cody was only 6 years old, Dial took him on a dayslong trek across Alaska’s all-but-uninhabited Umnak Island – an explicit attempt to indoctrinate his son into a life of adventuring.

When, decades later, this urge for wilderness adventure leads to his son’s death, Dial struggles with his own culpability.

“Those experiences made up our family lore, our history: hearing gibbons whoop at dawn, handling a flying lizard, eating exotic fruits. I took my eight-year-old son to Borneo’s wilderness. Was that negligence? It hadn’t seemed so then, but now I felt a sharp stab of regret.”

It’s no surprise that Dial ends up doubling down on his chosen life of wilderness and nature. But the quandary he expresses, of whether to urge one’s children to experience the world, with all its beauty and danger, or to keep them safe, is familiar, even to those parents sitting at the sports complex rather than in a tropical treehouse.

Also familiar is the recognition that “pristine nature” is not always what it appears. The tropical paradise of Costa Rica’s Osa Peninsula reveals itself to be what those familiar with the developing world’s wilderness areas might expect: a natural landscape inseparable from the human world. Dial’s growing disillusionment with the area – his increasing recognition of lies, violence, and political ineptitude – might be seen as a metaphor for the crumbling of the pristine nature myth. But he manages to avoid despair, or even negativity, while faced with the most heartrending of subjects.

“The Adventurer’s Son” is energized by spectacular descriptions of nature and by the narrative action of a father’s fight to find a beloved son. But it is its universality, this question of how to live and why, of how to understand nature, that gives it resonance and beauty.