‘A Good Provider Is One Who Leaves’ is extraordinary, moving

Loading...

Thirty years ago, as a journalist writing about poverty, Jason DeParle moved into a Manila shantytown and slept on the floor of a stranger, Tita Portagana Comodas, alongside various relatives and the scurrying rats. Before long the two weren’t strangers: Despite her imperfect English and his even worse Tagalog, not to mention their vastly different backgrounds, they became lifelong friends. Seeing Tita’s husband, Emet, and all five of their children take jobs overseas, DeParle, a reporter for The New York Times, came to grasp the importance of migration in alleviating poverty in the Philippines. The story of Tita’s extended family, set within the larger story of global migration, forms the heart of his stunning new book, “A Good Provider Is One Who Leaves: One Family and Migration in the 21st Century.”

Much of “A Good Provider” follows Tita and Emet’s daughter Rosalie, who was 15 when the author met her and who is nearly 50 now. Intelligent and quietly ambitious, she becomes a nurse, her education made possible by her father’s years working as a pool keeper in Saudi Arabia. Though her ultimate goal is to work in America, Rosalie first finds a job in Abu Dhabi, in the United Arab Emirates, where nearly the entire workforce is foreign-born.

She marries and has three children, but they are mostly raised by extended family in the Philippines while their parents work. At one point, Rosalie; her husband, Chris; and their daughter Kristina live in three different countries, “a family and a diaspora at once,” DeParle writes, “the national dilemma writ large.” After eight years in Abu Dhabi, Rosalie finally lands a nursing job in Galveston, Texas, and a coveted U.S. visa. Months later, her husband and children join her in America.

His recounting of Rosalie’s path to the U.S. makes evident the author’s intimate ties to the family. At times, he goes beyond being a journalistic observer, such as when he helps Rosalie prepare for her Skype interview for the Texas position and his intervention when her visa is held up, instances that underscore the privilege he possesses in comparison to his subjects. But DeParle is also aware that the family’s experience is part of a larger story, and he deftly alternates between their compelling saga and the broader issues surrounding migration.

Part of that big picture pertains to the special significance of migration in the Philippines. DeParle points out that “[n]o country does more to promote migration than the Philippines, where the government trains and markets overseas workers,” and with good reason: Overseas Filipino workers sent $32 billion home in 2018 alone. While the government promotes its citizens as good-natured and hardworking, DeParle also captures the intense loneliness experienced by migrants, particularly those separated for long stretches from their children.

DeParle also charts the history of immigration in the United States, providing useful context for our current political moment. He forcefully makes the point that there is a difference between the politics of immigration, which are broken, and immigration itself, which is successful in ways that are rarely acknowledged. Much of the divisive public discourse in the U.S. focuses on illegal immigration at the southern border. Rosalie, he notes, is “the kind of immigrant who is largely invisible in political debate but increasingly common. Since 2008, the United States has attracted more Asians than Latin Americans, and nearly half of the newcomers, like Rosalie, have college degrees.” Additionally, more and more migrants are women, as wealthy countries are increasingly in need of caregiving labor. There was a nursing shortage in Galveston in the wake of Hurricane Ike, and skilled Filipinos like Rosalie helped fill it. (Nursing is more prestigious in the Philippines than in the U.S.)

In addition to being intelligent and compassionate, “A Good Provider” is evocatively written. Describing the family matriarch when they first met, DeParle observes, “Tita faced crushing poverty without being crushed.” Writing of Emet, back in Manila after several years working in the Persian Gulf but unable to earn enough in his native country to support his family, DeParle notes that “Emet’s return to Saudi felt as inevitable as gravity.”

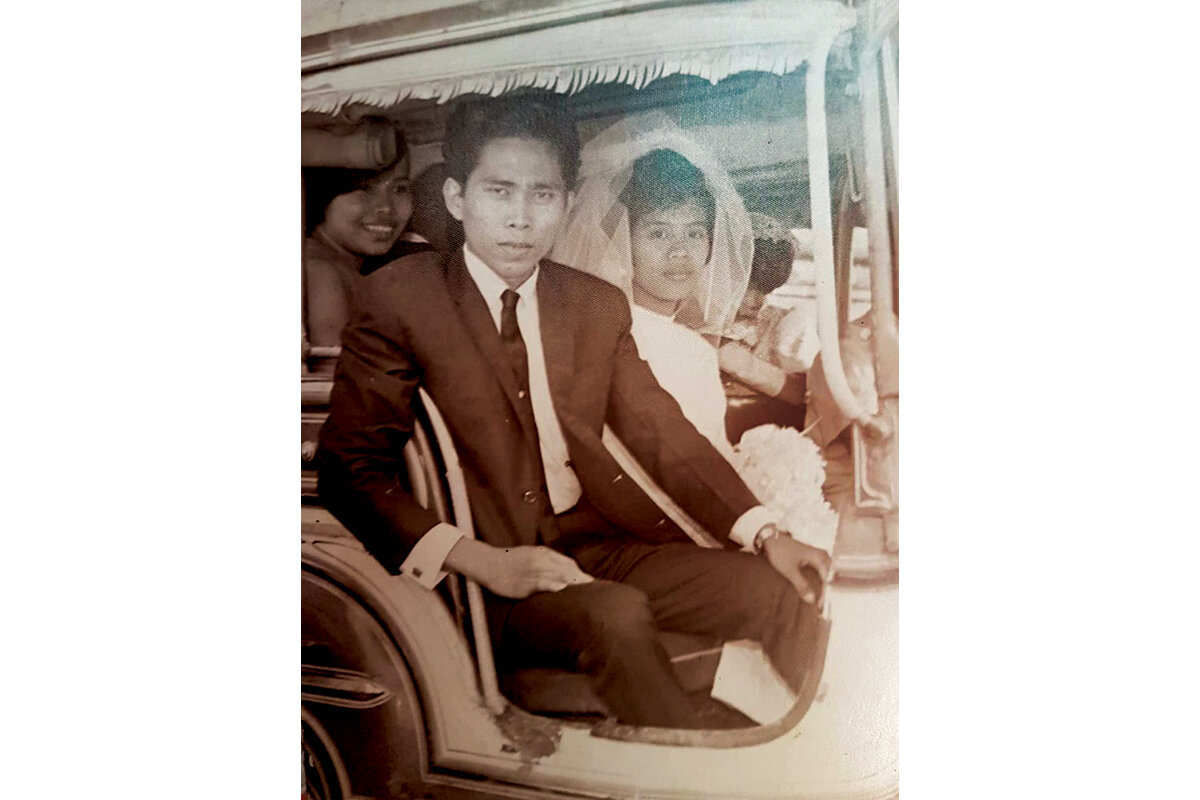

Emet spent 20 years working on and off in Saudi Arabia, where he was often unhappy. “Ever since his orphaned childhood, all he had wanted was a family,” DeParle writes, “but to support one, he had to leave it.” When Emet finally returns home for good, his children continue the cycle, leaving the Philippines to work overseas to support their parents and their own children. (The money Rosalie sends provides Tita and Emet with two-thirds of their monthly income.)

DeParle accompanies Rosalie’s family back to the Philippines for their first visit after four years in America. The children have mostly forgotten Tagalog, and their grandparents struggle to understand them even as they’re impressed by their strong English and the success of their American lives. As they’re preparing to return to Texas, Emet, weakened by a stroke, weeps. “Maybe I won’t see you again,” he says to his daughter. The all-too-brief reunion – held in the comfortable family compound made possible by years of overseas labor – captures so much about global migration: the necessity, the pride, the heartbreak.