'Ninety-Nine Glimpses of Princess Margaret' is unflinching, engrossing

Loading...

When Princess Margaret of the House of Windsor was born in 1930, the second daughter of the Duke of York and his wife Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon, the path of her life seemed to be laid out plain as parquet: She was at her birth fourth in line to the throne, but she would never be a queen. Her uncle, the Prince of Wales, would become king, get married, and promptly produce heirs. Margaret herself, her older sister Elizabeth, and her parents would be high-profile members of the Royal “firm,” shuttling from party to reception to parades to state funerals, being urged to avoid scandal, of interest mainly to dedicated Court-watchers.

What happened instead was a half-broken funhouse-mirror version of that assured future. When the old king died in 1936, Princess Margaret's uncle Edward ascended to the throne and immediately made clear that he intended to marry twice-divorced American Wallis Simpson. A crisis ensued, and in December of that year Edward abdicated – and suddenly Margaret's father was king, and Margaret's sister would be queen.

And Margaret? As Craig Brown makes mercilessly clear in his engrossing book Ninety-Nine Glimpses of Princess Margaret, she would still be an extra Royal, in the line of succession to a throne she would never inherit, in a bright international spotlight with all the scrutiny of celebrity but none of the power, a young woman in the absolutely horrifying position of not only having a strong-willed older sister but of having that sister be Queen of England.

Brown's book (first published in England as "Ma'am Darling") is the latest in a crammed bookcase full of biographies of Princess Margaret, but it's unlike any of them in its approach, telegraphed in its title: This is a collage of vignettes, some long and some short, drawn from hundreds of sources, some traditional and others not, some far more obviously trustworthy than others, and a few, sprinkled throughout the narrative, fictional – the author's what-if speculations on various turning points in Margaret's life.

In the eyes of an entire generation, the biggest of those turning points was romance between the Princess and Group Captain Peter Townsend, which ended when the Queen and her government decreed that if Margaret married the divorced Townsend, she would sacrifice her place in the line of succession, the royal succession status of any children she might have with Townsend, and her standing in the Church of England. In 1955 she announced to an eagerly-watching nation that she would not marry Townsend. In 1960 she married instead photographer Anthony Armstrong-Jones (created Earl of Snowden) in a union that produced two children but was very visibly unhappy right from the start. The marriage stumbled through years of infidelity rumors and long separations, with the two finally divorcing in 1978.

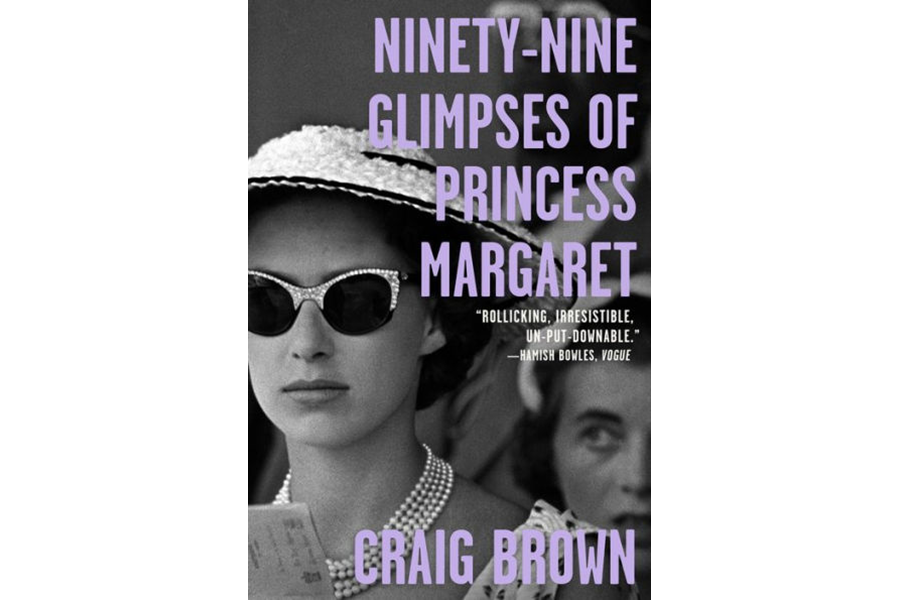

It was thus easy – and largely accurate – to see Princess Margaret not just as the most unconventional senior member of the Royal Family but also as its most famous victim (at least until Princess Diana later claimed that dubious distinction). Behind the jewels and the fashionable sunglasses and the polished appearances at one tedious public function after another, there was a palpable sense of tragedy, a feeling of thwarted pathos that drew raconteurs like flies to honey. Brown's book is the most artful, the most fascinating, and the most damning symphony of those raconteurs ever likely to be composed. He ransacks every biography, every memoir, every letter, every recorded anecdote, from Margaret's young girlhood to her death at age 71 in 2002, and he gives every gossip a turn at the microphone.

Since the most virtuous parish priest couldn't survive such a treatment, it's no surprise that a bitter bon vivant spectacle like Princess Margaret can't. She's traduced on almost every page of this book, with famous stories resurfacing about, for instance, her fondness for pulling rank: “She once reminded her children that she was royal and they were not, and their father most certainly was not. 'I am unique,' she would sometimes pipe up at dinner parties. 'I am the daughter of a King and the sister of a Queen,'” Brown relates. “It was no ice-breaker.”

Likewise the more pious biographers of the Royal Family are archly mocked, such as William Shawcross for his massive authorized biography of Margaret's mother: “Wherever she does, she delights everyone, and they are in turn delighted by her delight, whereupon she is delighted that they are delighted that she is delighted that … and so forth,” Brown writes. “If you shut his book too abruptly, you'll notice delight oozing out of its sides.”

There's plenty of delight in "Ninety-Nine Glimpses of Princess Margaret" as well, but it's a very pointed kind of delight, crafted perfectly for the lover of acid deadpan and knowing innuendo. It's exactly the kind of book Princess Margaret herself might have enjoyed – about anybody but herself.