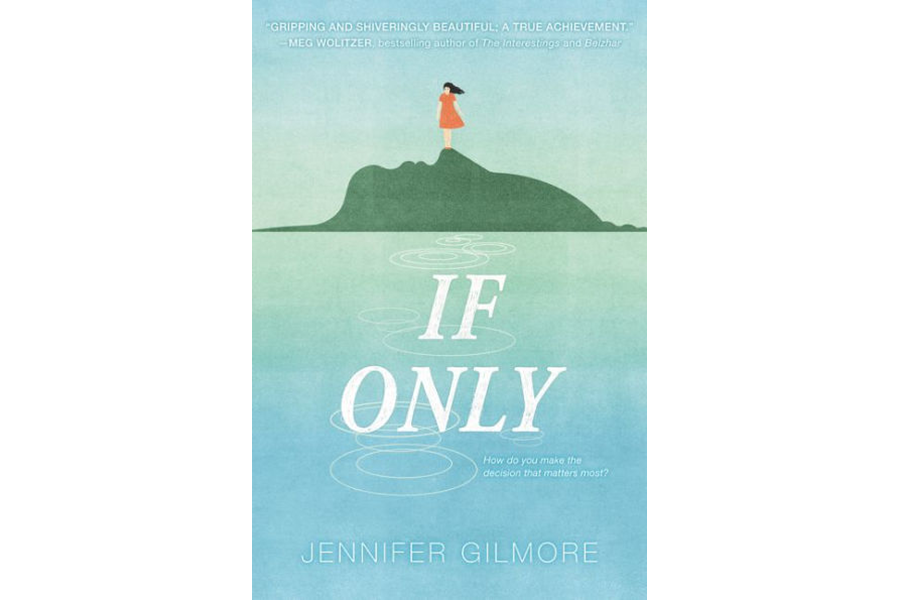

'If Only' explores an adopted child's sense of a kaleidoscope of possibilities

Loading...

Is an adopted child wanted or unwanted, chosen or rejected, lost or found?

This is the central dilemma for Ivy, an adoptee who decides to find her birth mother, Bridget. At 16, Ivy has reached the age that Bridget was when she was born. The compulsion to find her awakens in Ivy like a light flicking on in an abandoned house, and there’s no switching it off.

Jennifer Gilmore’s second young adult book, If Only, drops readers in the deep end from page one. There’s no time for silly or light, what with so much poetic introspection to undergo. Raw stories about adoption may be this lauded author’s specialty; her adult novel “The Mothers” dealt with the seeking couple’s side of the story.

“If Only” alternates between Bridget circa 2000, Ivy circa 2016, and a handful of alternate timelines in between. The jumpy structure somehow works, mirroring the lyrical, scatterbrained, hyperbolic, elliptical style of teenagers thinking through some deep things.

On Bridget’s side, the possibilities for her unborn baby stretch endlessly upward – she could give the baby a life so much better than her own.

Facing pressure from her cold, religious mother and apathy from her ex-boyfriend (who broke up with her before either knew she was pregnant), Bridget struggles to commit to placing the baby for adoption at all. From beginning to end, she vacillates between wanting to raise her daughter herself and, as she says, loving the baby too much to withhold a better life from her.

We trace her interviews with prospective parents over several months as she tries to chart a path. In these meetings, Bridget is drawn to the women, constantly wondering what makes one a mother and how she can be trusted with a decision that affects so many lives at once.

“I’ve got what all of them want,” she thinks. “This baby inside me, she could inherit the world, all sky and moon and sun and stars. All for her, this world. It’s already getting away from me. I don’t know what I want in it for me. How am I supposed to know all this now? The future, the future. It is as far away as the planets. But I feel it growing nearer. I am scared of it.”

Meanwhile, in a parallel storyline 16 years later, Ivy performs the same dogged soul-searching as she digs to find her birth mother. For Ivy, the threads of possibility run backward over her shoulders in a blind tangle. She’s determined to unravel them and make a pattern for herself.

Her relationship with her adoptive parents, Andrea and Joanne, is wonderful, but she can’t shake the indeterminate ache from the invisible yet seemingly omnipresent third woman, her “first mother.”

At one point, she says to her boyfriend, “I laugh totally different. I have never heard anyone with my laugh.” When she asks him to tell her what she sounds like, he responds, “You.”

“Well, I want to sound like someone,” she says. There are some things adoption can’t replicate, it seems.

Acknowledging how blessed she was in her adoptive family, Ivy says, “I am lucky; I am special. In a way it’s more and in a way it’s less but no matter what, I am always holding on to these two things at once, these two stories, these two ways of seeing things, and I can’t say I’ll ever really know if I was lost or if I was found.”

Somewhere in that yarn snarl is a moment of choice, and this moment is what Ivy agonizes over. Her story could have been so different. She could have been anything, anyone; so could Bridget and her ex, just kids themselves.

So Gilmore shows us glimpses of those alternate timelines, the “if only” lives that never happened. Ivy’s story could have been one of Sage in Arizona, Poppy in New York City, Ivy raised by Bridget, etc. Each version differs in location, cast, and satisfaction, but all feature a best friend and a searching heart.

Reading these timelines is like studying geological striations in multiple canyons and trying to match up their fault lines. We may see recurring elements in the background and intuit how one life differed from another, but ultimately, each took its own path. Gilmore simply writes an elegy for the selves that could have been.

Gilmore’s quiet triumph is in writing a novel that is thoroughly from the female perspective yet devoid of misandry. This is a story of girls and women, of assessing what being female means in a family, of flowers trying to know when to bloom. Sure, there are men in the story – fathers, boyfriends, best friends, strangers – but every choice is the women’s on their own feet.

My favorite element was the tender, resolute bond between Ivy’s two moms, Andrea and Joanne. Piece by piece we learn their backstory and fall in love with them. They’ve gone through it and come out with a love deeper and stronger than the world around them can shake, try though it might.

“If Only” tackles big questions that women face at all ages. Am I the best me possible? What makes a woman a mother, if not biology? How do I know when a decision is right or wrong, if I can’t predict what the outcome will be?

“If Only” is a work of heart, labored over and full of finesse. Take time to process it.