'The Pope Who Would Be King' details the birth of the modern papacy

Loading...

Pope Francis, the current supreme pontiff of the Catholic Church, wields two different kinds of authority, one vast and one minuscule. The vast one is obvious: The Pope is seen as the heir to St. Peter, the spiritual leader of the world's more than 1 billion Catholics. The minuscule one is often something people have to make an effort to remember: The Pope is also the chief executive of a kind of government, the head official of the Holy See, which is quartered in the 110-acre confines of Vatican City in Rome. As pontiff, the Pope is one of the most powerful and influential movers on the world stage. As head of state, he rules a country that could be conquered in 15 minutes by a random day patrol of the Polizia di Stato.

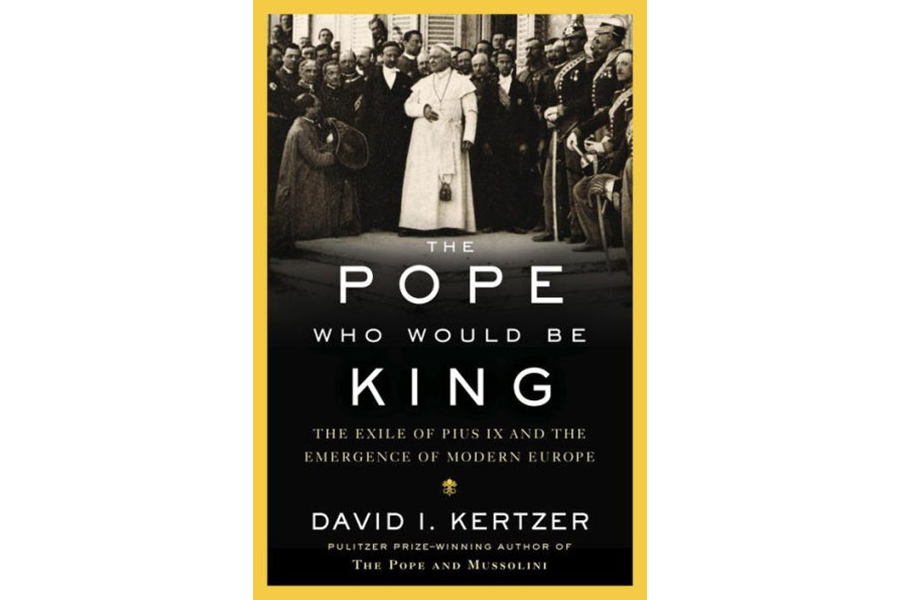

As David Kertzer points out in his richly rewarding new book The Pope Who Would Be King: The Exile of Pius IX and the Emergence of Modern Europe, this wasn't always the case. For more than a thousand years, Popes were princes, with armies and vast territories over which they ruled as secular (at times very secular) monarchs. Kertzer, who won a Pulitzer Prize in 2015 for his book "The Pope and Mussolini," details in his new study the crucial moment in history when all that changed.

That moment was a man: Giovanni Mastai-Ferretti, who was born in 1792 and elected Pope Pius IX in 1846 when his generally disliked predecessor, Gregory XVI, died. He was quickly nicknamed “Pio Nono,” and as Kertzer puts it, “He was a man with benevolent instincts and deep faith but woefully limited ability to understand the larger forces that were transforming the world,” and as a direct result of that limited ability, “he would be the last of the pope-kings, a dual role central to church doctrine and a pillar of Europe's political order for a thousand years.”

Those forces transforming the world would crest only two years after Pius IX ascended to the throne of Saint Peter. In 1848, a wave of nationalist revolutions swept through the Western world. In Italy, the Risorgimento led by men like Giuseppe Mazzini and Giuseppe Garibaldi was at first encouraged by the new Pope, who granted amnesties for political prisoners and at least flirted with the idea of instituting some progressive democratic reforms throughout what was then still very much his terrestrial kingdom. This fit well with the tumultuous times; as Kertzer writes, “After centuries of oppression, the people were at last rising up to assert their rights. The tide of history had changed.”

As "The Pope Who Would Be King" makes clear, Pius IX ultimately proved to be just about the last person who could navigate that shifting tide. When his conservative minister Count Pellegrino Rossi was assassinated, Pius felt the ground tilt beneath him (“Rossi had been the government,” Kertzer writes. “Now that he was gone, a great void had opened up”) and fled into exile, where his moods “lurched between stubborn intransigence born of a feeling of betrayal and an eagerness to regain the affection of his subjects.”

Kertzer tells this story in greater detail and with more infectious energy than it's ever been told in English, and he never loses sight of the crucial larger issues that were at stake when armed mobs stormed the Papal territories. Since its inception, the papacy had always had a dual nature, with one foot in the spiritual world and the other in the temporal world, and Papal authority, being seen as having come directly from the hand of Jesus Christ, had been the keystone of all other ruling authorities. “With the fall of the pope-king,” Kertzer writes, “the rationale for people elsewhere to accept their humble places in society as God's will, their leaders as supernaturally sanctioned, could not long survive.”

When the dust settled in 1850 and Pius IX returned to Rome, he was no longer the “simple, sweet, timid, fearful” country priest Victor Hugo had once described him as being, and the papacy itself was vigorously shaking itself into the form it would hold ever since. Pius continued as head of the Church (he died in 1878 as the longest-reigning Pope in history), but Kertzer describes a very different man after the exile and return: “It was only by weaning himself from what he now recognized as his weakness, his great desire to be loved by his people, that he could face the future,” readers are told. “He would need to develop a protective shield, to turn not to the people for approval but to God alone.”

He convened the First Vatican Council in 1869 (the subject of John W. O'Malley's superb upcoming book "Vatican I") , and in 1870 the doctrine of papal infallibility in matters of faith was formalized: What the papacy lost in territory it regained ten times over in spiritual authority.

"The Pope Who Would Be King" tells the very human story of this modern rebirth of the papacy, one of the world's foremost tales of political survival.