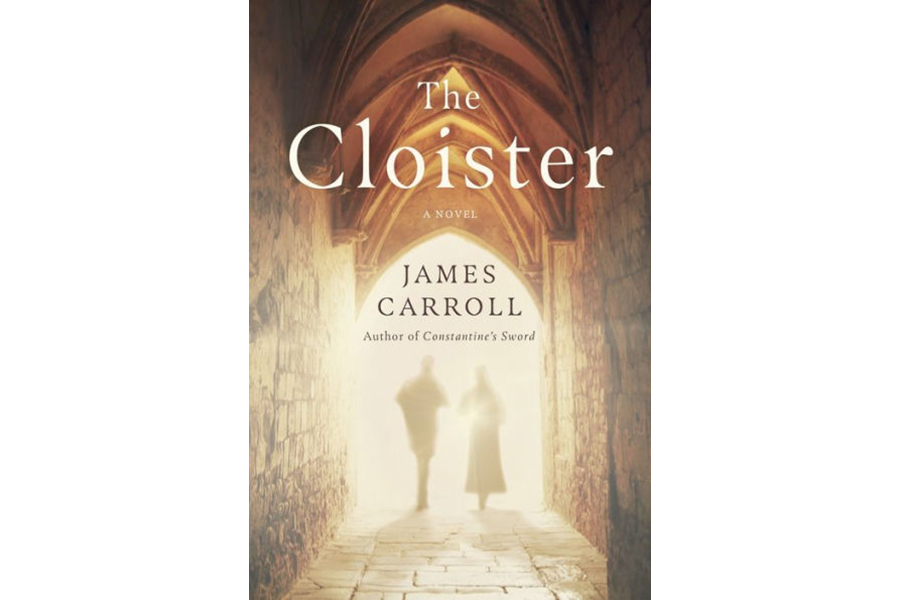

'The Cloister' probes deeply into matters of faith, dogma, complicity, and forgiveness

Loading...

With The Cloister, James Carroll manages a balancing act that would have thwarted lesser novelists. He juggles three stories, from different eras, that each probe deeply into matters of faith, dogma, complicity, and forgiveness. The book, as its title suggests, has a great deal of religion at its center, specifically Roman Catholicism. It's a tradition that Carroll knows well, both as a historian and a former priest.

Readers familiar with his previous work, especially the 2001 nonfiction book, “Constantine’s Sword: The Church and the Jews,” will recognize at least one of Carroll’s preoccupations in this novel: the idea that 20th-century anti-Semitism had its roots in the Catholic Church’s centuries-old assertion that the Jews were to blame for the death of Jesus Christ.

The book’s two main characters are Michael Kavanagh, a priest, and Rachel Vedette, a Jewish Holocaust survivor, who meet in the unlikely setting of The Cloisters in New York in the 1950s. The Cloisters is the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s outpost of medieval art atop Fort Tryon Park, overlooking the Hudson River. As the two protagonists become acquainted, the reader begins to understand that their present lives are deeply affected by their perceptions of past mistakes.

We learn about Rachel largely through flashbacks to her life in Nazi-occupied Paris, when she helped her father research an important book on the 12th-century Christian philosopher Peter Abelard. The monk, whose name has been linked with that of his paramour, Héloïse, was an early supporter of Jews in France. The church condemned Abelard as a heretic, effectively silencing his campaign to change church attitudes about the Jews.

Rachel and her father believe that Abelard’s writings point to a fork in the road for Christianity. The story “could have gone another way, and the pivot point, ages ago, was the place of the Jews.” By publicly identifying France’s legendary monk-hero with tolerance toward the Jews, they hope to change the minds of their fellow citizens, whose fear of the Nazi occupiers and hatred of the Jews (fueled by centuries of church-sanctioned vilification) is leading them to betray their Jewish neighbors.

As a counterpoint to Kavanagh’s and Rachel’s stories, the book also weaves the tale of Héloïse and Abelard, “the Romeo and Juliet, Tristan and Isolde, Lancelot and Guinevere of la France.” Their devotion to each other, body and soul, showed through their letters when they were forced to live apart (he was banished to a remote monastery, she was sent to a convent). Readers looking for salacious details about their relationship will be disappointed, because author Carroll is more interested in minds than in bodies. In particular, he gives Héloïse the role of Abelard’s champion: She’s the one who preserves Abelard’s writings for a future age, hiding his manuscripts in the cloister garden. It’s a nice touch, to point out that this powerful noblewoman was the first person to recognize the future implications of Abelard’s teaching, not just as it related to the Jews, but also as it regarded the nature of God’s universal love.

This is heady stuff for a novel. Carroll, as religious historian and church insider, goes into a fair amount of ecclesiastical detail about the 12th century, which will fascinate some readers and send others skimming to the end of the chapter. But he keeps the action moving along, particularly in the Paris scenes as Rachel’s story plays out against the backdrop of French collusion with the Germans.

Carroll is at his best in the last few chapters, when he explores each of his characters’ feelings of culpability for the tragedies that they knowingly, and unknowingly, set in motion. For Héloïse, Rachel, and Kavanagh, the challenge is how to move forward, fully conscious of the hurts they’ve inflicted, but not seeking a facile or temporary forgiveness. Here in the braiding together of the three stories, past and present, Carroll shows that for his characters, and indeed for all of us, the greatest wisdom may lie in forgiving oneself.