Madeleine L'Engle bio 'Becoming Madeleine' is aimed at middle readers but is also interesting to adults

Loading...

Madeleine L’Engle often said she didn’t write for children, even though her 1962 breakout book, “A Wrinkle In Time,” became a groundbreaking classic for young adult readers. In many ways, the book transcended simple labels. Heroine Meg Murry was gawky and imperfect – and smart and courageous. The plot was officially science fantasy, but drew on ageless themes from faith to physics to familial love.

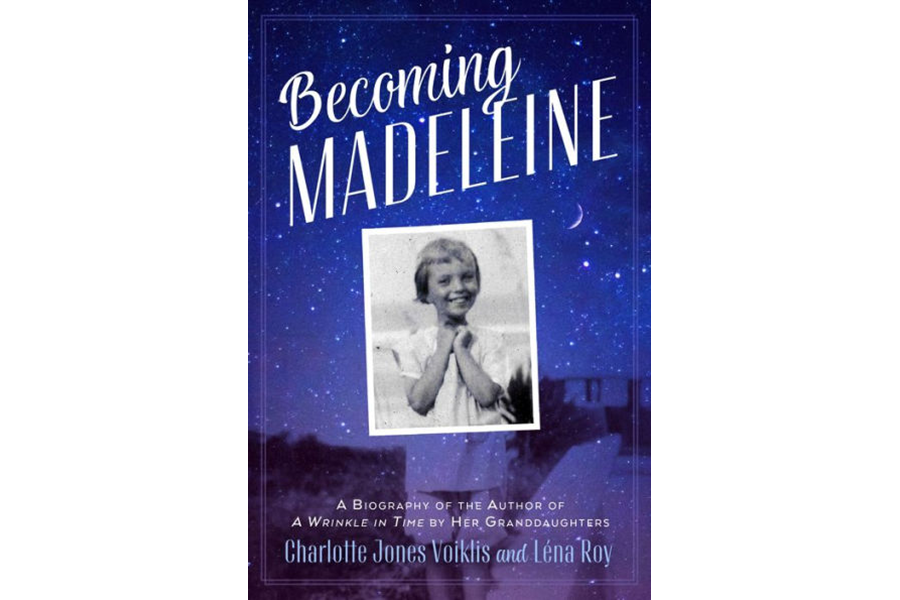

It’s fitting, then, that Becoming Madeleine, a L’Engle biography written by her granddaughters, Charlotte Jones Voiklis and Léna Roy, is aimed at middle readers but is also interesting to adults. The life of this sensitive, insightful woman – at least, the 40-plus years that the book covers – is as absorbing as a novel.

“Becoming Madeleine” is timed for the much-anticipated movie adaptation of “A Wrinkle In Time,” which will open in theaters March 9. The story is liberally studded with excerpts from L’Engle’s diaries and letters, an almost collage-like approach that also features interesting ephemera from handwritten letters to school report cards. (Readers whose brilliance was equally unappreciated in school will enjoy the chilly comments from her teachers.)

Tender-hearted and fiercely observant, L’Engle had an unusual upbringing that included a move from New York City to the French Alps after the stock market crash of 1929. From an early age, her career was self-determined.

“I have to write, there is no doubt about that…” she wrote as a teenager.

At 31, she considered what she wanted to achieve through that goal. “I … would like my books to make their readers want to be more than they are, to reach higher. I want to make them – the readers – aware of the wonderfully exciting and unlimited possibilities of man.”

“Becoming Madeleine” is a surprisingly valuable resource, given its young target audience and given that L’Engle outlined so much of the same story in her own published works before her death in 2007. She wrote more than three dozen books over a career that spanned more than 50 years, including a raft of adult and young adult fiction where characters from one series often crossed paths with those from another. She wrote plays, poetry, religious essays, and, most relevant here, a series of introspective memoirs.

Devoted readers thought they knew her well, through her memoirs and through the biographical details she loaned to her fictional characters. They had read about her unhappy experiences in boarding school, how she became an actress to enhance her writing skills and career, how she fell in love with a young actor, Hugh Franklin (who went on to some fame as Dr. Charles Tyler on "All My Children"), how "A Wrinkle In Time" (“my psalm of praise to life, my stand for life against death”) was rejected by 26 publishers.

But that familiarity was frayed after a 2004 New Yorker profile revealed L’Engle’s family referred to her memoirs as “pure fiction” and resented how she had mined their own lives for the books officially labeled as fiction. By that account, her career had damaged her relationships with her children and her marriage was far from a fairy tale. The truth – if there is a single truth – was also hard to pin down in a biography by Leonard S. Marcus, “Listening for Madeleine,” where people who knew L’Engle presented vastly different views of her life. It’s been hard not to long for more information about her, the same way we’d hope for the final word on Meg Murry or Vicky Austin.

“Becoming Madeleine” is an enjoyable guide for young readers who know nothing of this, but it’s also helpful for L’Engle devotees trying to reconcile the many facets of a complex human. Voiklis, who manages L’Engle’s literary business, and Roy, an author, take a respectful but straightforward approach to her story. The chronology lets them avoid the thornier discrepancies from later in L’Engle’s life, skipping quickly through her married life and ending the story abruptly with the publication of "A Wrinkle In Time." It feels truncated, though the authors wrote in an afterward that it was a logical breaking point for young readers and allowed them to “respect the privacy of her journals and travel gently through them, especially those from the time when we knew her.”

Poignantly, in her memoirs, L’Engle wrote with great affection about her young granddaughters and the delight they brought to her life. A generation later, bending space and time through the power of words, they’ve brought that joy full circle.