'Traces of Vermeer' strives to figure out the actual nitty-gritty of Vermeer's craft

Loading...

Juriaan van Streeck was born in Amsterdam in 1632. He married at 21, had nine children, moved around from job to job, and was for years an extremely accomplished painter specializing in still lifes of remarkable texture and craft. He died in 1687, and today, four centuries later, his name is known only to a few art dealers and connoisseurs of the Golden Age of Dutch painting

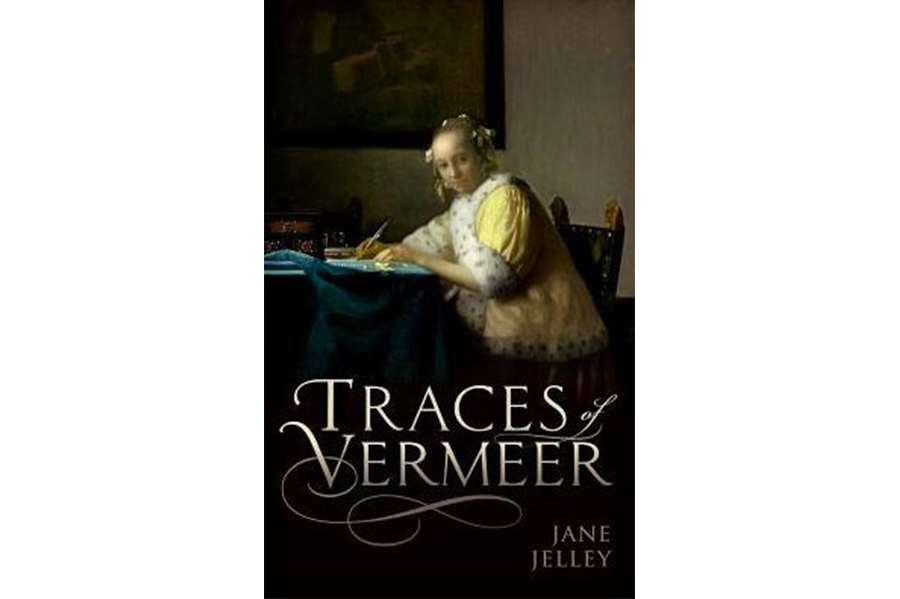

Also born in 1632, less than 50 miles away in the Dutch town of Delft, was another painter. He, too, married at 21, had children (15 instead of nine), moved around from job to job, and was for years an extremely accomplished painter specializing in works of remarkable texture and craft – landscapes, still lifes, and scenes of intimate home life. He died about a decade earlier than Juriaan van Streeck, in 1675, but his name is known all over the world. He's more famous in the modern era than he was in his own day, and the last of his paintings to come to auction sold for $30 million. He's Johannes Vermeer, and he's the subject of Traces of Vermeer, a meaty and intensely interesting new book by Jane Jelley.

In a very real sense, almost every book ever written about Vermeer has tried to understand the difference between him and Juriaan van Streeck – or any of dozens of other painters of his time – and this latest is no exception. Jelley is a painter in her own right, and she writes with that hard-won authority: “The task of an artist is to make his picture something more than the sum of its parts; and very few ever have managed this better than Vermeer.”

She undertakes the task of figuring out the actual nitty-gritty of Vermeer's craft – the composition of the pigments he used, the feel of the canvas on which he worked, the marvelously shifting play of light, which seems particularly to fascinate her. “Vermeer's subjects seem to be illuminated more strongly than you would expect,” she writes, “that they contain more light than they receive through the windows.” In her book's best chapter, she not only delves in-depth into the controversial question of whether or not Vermeer used a camera obscura apparatus and merely traced and reversed its projections in order to achieve his results but attempts to re-create the process herself. She notes with finely-controlled irony the impatience of modern-day analysts to solve the mystery of this painter: “How can anything be beyond us? We, who have the technology at our command to project a voice across the world; to tranquilize a tiger; to cure a plague.” Surely, she taunts this consensus, the centuries-old work of this one painter shouldn't baffle.

She comes up with her own theories about those oddly, indefinably gorgeous paintings, and having sampled her evidence, readers will no doubt argue vigorously. Through her own understanding of the craft, she comes as close as anybody can to understanding both the mechanics and the inner lives of masterpieces like "A Lady Writing," "Young Woman with a Water Jug," "A Woman Holding a Balance," or "Girl with a Pearl Earring." And she's bluntly honest enough to acknowledge repeatedly that these investigations only reach so far. "The frustration is, that whatever answers we suggest to the puzzles Vermeer left behind, the only certainty is that we will never know if we are right," she writes. "He has left his masterpieces behind; accompanied only by a deep silence."

Along the way, however, Jelley infuses her descriptions of Vermeer's world with a vivid immediacy, taking readers into the hustle and bustle of market day in Delft (“Everywhere there is a throng of people, eager to be out, to share a joke, exchange gossip”), or down the narrow streets in a storm: “The squalls sweep across the cobbled streets, and swirl in arcs across canals; piercing their swollen surfaces with a thousand hissing needles. Water drums against brick, stone, and tiles, it sheets from the steep roofs, and twists in fat, dark streams out of the gutters onto the alleyways.” It quickly becomes an immersive reading experience, like an excellent historical novel with 62 pages of fine-type end notes attached to help with further inquiries.

“Scientific analyses can tell us what pigments and oils were on his canvas, and indicate the order in which the paint was applied,” Jelley writes. “It cannot tell us what Vermeer actually did.” And this is the key concession of her book: that all the analysis in the world of charcoal dust and lensing gadgets and print-tracing won't ultimately bring us usefully closer to understanding why we venerate this painter while forgetting so many of his peers. As Jelley points out, the paintings are more than the sum of their methods and ingredients, which are the only “traces” of Vermeer we can track and duplicate. The rest is magic.