'George and Lizzie' proves Nancy Pearl can also be a storyteller

Loading...

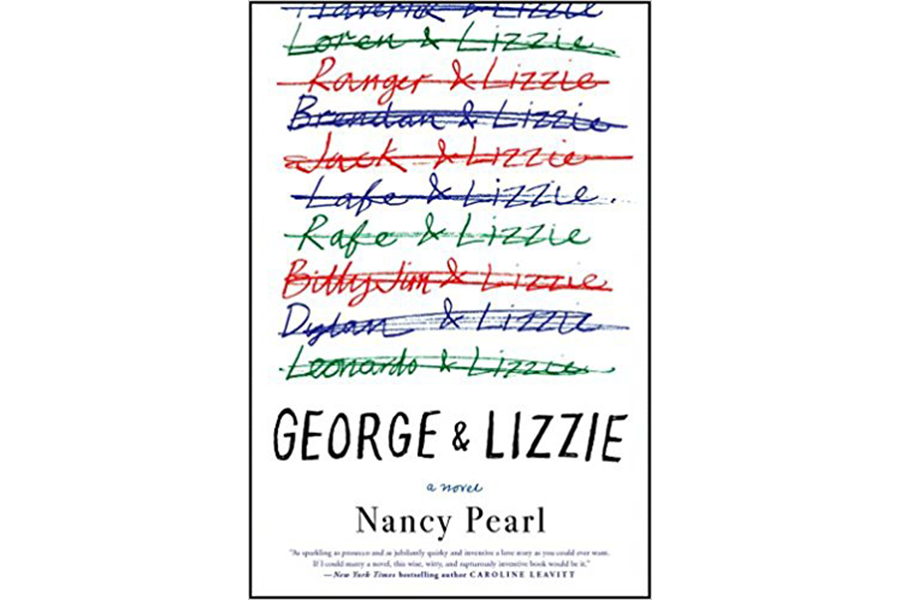

The inevitable question about George & Lizzie, Nancy Pearl’s first novel, is how it stacks up to its author’s own tough but loving standards.

Pearl, as close to a celebrity as a professional librarian can be, is renowned for her ability to connect readers with great reads. She’s written a handful of “Book Lust” recommendation guides, among other accomplishments, and holds to a “Rule of 50” that says it’s OK to abandon a book if the reader isn’t engaged after the first 50 pages. (You can subtract one page for each year the reader is over 50.)

In the case of "George & Lizzie," I’d bet librarians and booksellers will match it to readers who love clearly-imagined characters (as Pearl herself does). They’ll suggest it to bibliophiles who have a weakness for smart dialogue and mordant humor, and a sympathy for the painful mistakes people inflict on themselves and others. It may appeal to fans of Anne Tyler, who has a similar talent for plots that seem unlikely at first and then intensely human.

While the title gives equal weight to both George and Lizzie, it’s chiefly the story of Lizzie Bultmann, who we meet as an aspiring college English major who reads Dodie Smith’s “I Capture the Castle” and loves “an eclectic group of poets” including Edna St. Vincent Millay. The child of two behavioral psychologists who are – at least through Lizzie’s eyes – almost caricatures of coldness, the defining moment of Lizzie’s life has been a high school goal she set herself; The Great Game, a self-destructive lark that Lizzie thought might awaken her aloof parents “enough to finally see her.”

The eyebrow-raising game and its harm are complete by the time we meet Lizzie and kind, upstanding (but don’t get complacent, Pearl slips in some surprises) George Goldrosen.

“The Goldrosens never tell what our gifts are in advance of giving them,” as one character says, and George’s contributions are vast.

At heart, the book is the story of the couple’s marriage and the question of whether Lizzie can transcend her emotional walls, but we learn the details through storytelling vignettes that smoothly spool back and forth through time. That style and the 1990s setting lend the story a slightly formal, old-fashioned quality, allowing plot twists that 21st-century advancements might have eliminated. In today’s world, for instance, Pearl’s college students might have been on Instagram rather than consulting Ouija boards, and electronic traces would make it much harder for a major character to plausibly disappear.

The pace is abrupt at the very beginning, then settles down to a relaxed back-and-forth survey that skims through the character’s lives, inching the story forward here and pausing to develop a detail there. It’s a surprisingly delicious read considering how many of the main plot points are revealed in the first few pages. And by this reader’s count it’s still pretty early in the rule of 50 – on page 23, when Lizzie meets her college roommate, Marla – that we fall a little in love with the not-always-likable title character, and know the book will keep us emotionally attached to the end.

It’s at the end, if anything, where the pace feels off, wrapping up the story and its conflicts with jarring speed. One story thread that seemed bound for importance simply drops off instead, others are compressed too fast. But it’s to Pearl’s credit that we want more time with Lizzie and George (and Marla and George’s mother Elaine and Sheila and others), and this whole improbable community that she’s brought to life.