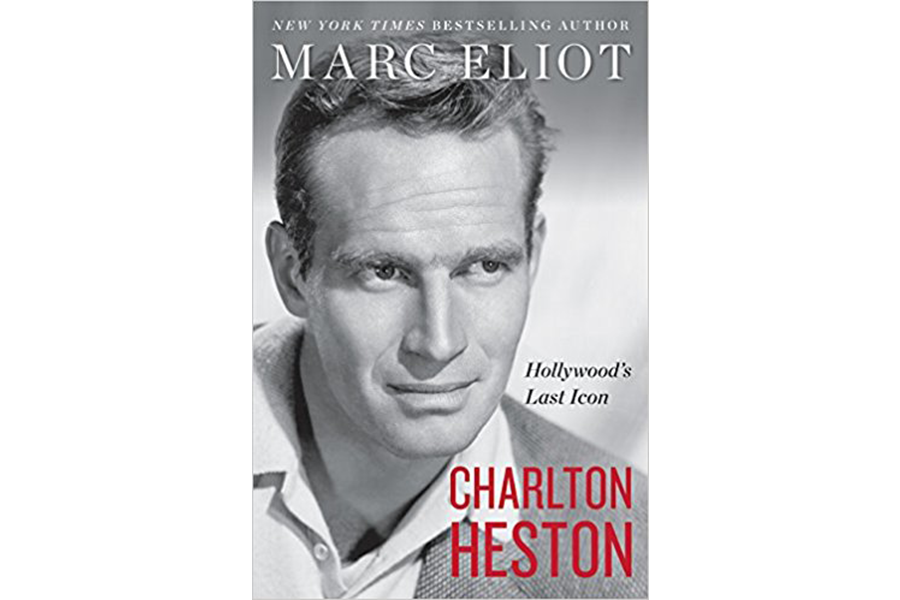

'Charlton Heston' is a voluminous, possibly definitive, study of a Hollywood paragon of masculinity

Loading...

Dense biographies about high-wattage Hollywood stars with limited acting chops can be tricky business for a writer and a reader alike. The former has to instill in the latter a belief in why we should care beyond yet another exegesis of celebrity, while readers, ideally, find a way to open themselves to seeing old works anew.

Marc Eliot has this kind of challenge in hand with Charlton Heston: Hollywood’s Last Icon – a voluminous, and possibly definitive, study one of the big screen’s paragons of brawn and masculinity. Its subject looms large in our cultural memory while remaining a limited thespian whose go-to move was leaning forward, iron jaw extended, as if forever contemplating where to get a good steak.

But if Heston lacked range, he didn’t lack self-consciousness. He was an ardent diarist, and those writings are counted on to provide new vantage points, Heston’s prose teaming up with Eliot’s, as it were, in a joint mission to tell us why we should care more than we already do about this Tinsel Town icon.

For starters, we should care because of the people Heston worked with, and what his relationship with them reveals. Consider, for example, Orson Welles, with whom Heston paired in 1957 to film the still incredibly odd, incredibly creepy B-noir "Touch of Evil." Throughout this book we see Heston launching himself into intense workouts to get in shape for his parts, like he’s training for some epic last-man-standing competition, with lots of tennis worked in. He often comes off as a pawn for cagey directors but a thinking pawn all the same, with a sensitive B.S. detector making up the deficiencies of top-shelf mental acumen. In college he screened and loved "Citizen Kane," and it was Heston who got Welles the directing gig for "Touch of Evil," when no one in Hollywood would so much as prod Welles’s corpulent midsection with a barge pole.

Like so many Welles projects before it, "Touch of Evil" was hamstrung by what producers considered over-artiness, with Heston quite rightly realizing that he was a pretend star – behind Welles – in a picture that was only being made because he could draw an audience. Heston found himself having to act as go-between for the studio with an increasingly disconsolate director, who believed his leading man was a turncoat in part responsible for shearing his vision from him.

But outings like this one were the exceptions, of course. Heston was an action man, and Eliot’s book is structured around the monuments of his stardom: films like "The Ten Commandments," "Ben-Hur," and "Planet of the Apes." It’s a list that not only defines Heston’s career but a considerable chunk of what is still well remembered from Hollywood in the late 1950s and 1960s. If you’ve seen any film in your life outside of a Netflix-and-chill context in the most perfunctory film class – or hell, if you just ever leave the TV on at Easter – you’ve assuredly seen at least one of them. And if you’ve not seen "Planet of the Apes," you’ve seen its ending spoofed somewhere. Heston’s physicality and the toll taken by the "Ben-Hur" shooting were integral, we see, to his performance. Worn down, almost like he’d been rubbed into the nitrate itself, Heston cries real tears as his character watches the Christ figure die in the film’s final shot. You watch the performance and you’re surprised, perhaps, how truly this stoic figure is emoting, with some context now worked in to flesh out one’s understanding of a scene. "Ben-Hur" becomes even more human a picture, and there even seems to be something preternatural about the fact that Heston performed all but two parts of the epic chariot race.

Eliot’s portrait of Heston’s life does take some turns off the set, and we catch glimpses of a fascinating political figure, so far as actors go, one considerably more protean than we now think – teaming with Martin Luther King, Jr. one moment and regularly stumping for the NRA the next. (In fact, Heston’s positions on guns are more nuanced than the anti-firearm brigade would likely expect.) But Eliot’s clear preference is the world of film, putting us right there with Heston as he mulls scripts, trains, launches himself bodily and mentally – both so far as each aspect of him went – into epics, biopics, big pictures, small pictures, more or less equally.

"Heston: is at its best here, revealing its subject as downright ruminative while working on "The Ten Commandments," having prepped to the hilt to ready himself to play Moses. You even get the sense of some bonding/twining across the ages going on between the Red Sea parter and the Hollywood hunk: “All the Mosaic literature I’m working through, all the times I’ve read the script, mean little compared to the weeks I’ve spent wearing Moses’s clothes and breathing the air he knew.” A post-shooting bath prompts a joke about trying to part the water in the tub. You don’t expect sly wit from Heston. But when you see it on view in these pages, you realize how his performances gained in power from that push-and-pull between what was emoted and what was held back – which fosters a unique actorly visual all its own. After all, a biographer could always provide a more fulsomely emotional display — almost like production notes for a life and career – and now one has.