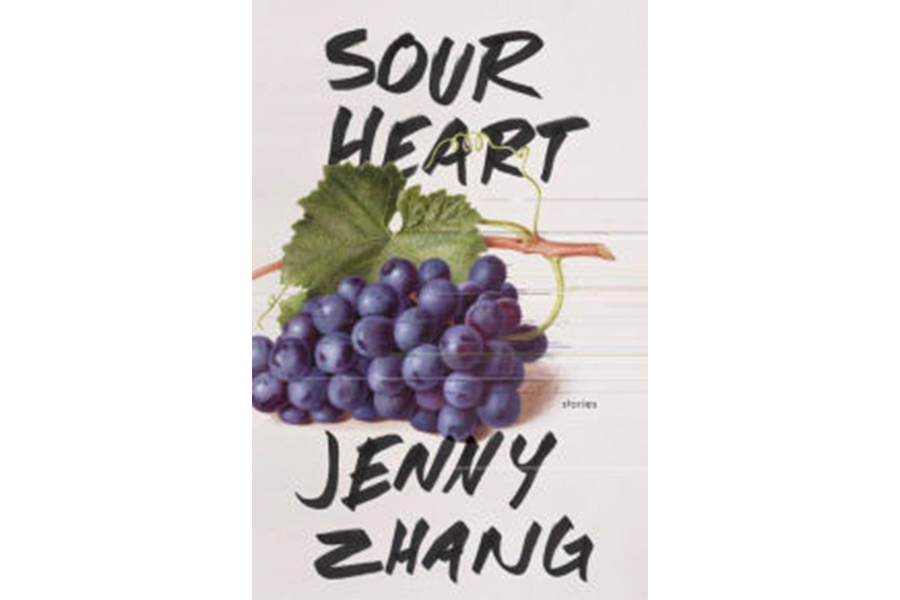

'Sour Heart' author Jenny Zhang illuminates the immigrant's struggles to belong

Loading...

“Lena Dunham is like my fairy godmother,” Jenny Zhang revealed in a recent interview with The Guardian, albeit one who tweets and emails with unsolicited offers of editorial help. In the often capricious world of publishing, Dunham – actor/director/producer, best known as the creator of HBO’s iconic series "Girls" – is probably one of the few media powerhouses able to wield a magic wand. With her "Girls" writer/producing partner, Jenni Konner, Dunham launched the feminist, fiction-and-nonfiction-mixed Lenny Letter online in 2015; getting their own Lenny imprint at Random House (which published Dunham’s “Not That Kind of Girl”) seems to be the natural progression for the influential duo. Their inaugural title is Zhang’s Sour Heart.

Already a published poet (“Hags” and “Dear Jenny, We Are All Find”), the Iowa Writers’ Workshop-trained Zhang makes her fiction debut with a collection of seven loosely linked stories highlighting the Chinese-American immigrant experience, told predominantly through voices of, not surprisingly, girls. Some are Chinese-born transplants, some are American by birth, and all have parents who made the decision to leave everything familiar and start new lives on the other side of the world in New York City boroughs.

The first and final stories feature the same family’s experiences told decades apart by the eponymous “sourheart,” one of the many endearments for Christina, the daughter of an immigrant couple desperate to establish a permanent home for their small family. Mired in poverty in “We Love You Crispina,” Christina’s parents are “disastrous and depressing in [their] ability to get ahead.” Unabashedly spewing four-letter words by third grade, Christina never doubts she is “loved [her] entire life by parents who vowed daily to spend their whole lives protecting [her]” despite the family’s multiple displacements from one horrifying living situation to another – 14 cockroaches crushed overnight on a single calf, desperate bathroom runs to the across-the-street gas station, their stolen belongings being sold on the corner for prices they can’t afford. Decades later, in the ending story, “You Fell Into the River and I Saved You!,” the family’s newest member – Christina’s younger U.S.-born sister – will move into her first apartment in one of their former neighborhoods, now transformed from squalor to chic.

Of the five stories in between Christina’s bookends, Zhang ingeniously, subtly links the narratives through the various homes Christina’s family was sometimes forced to share: with reluctant friends who have a little extra when Christina’s parents have less than nothing, in a rented room meant for two that houses 10 people on five mattresses. Amidst this shared indigence exposed in the opening story, Zhang skillfully introduces the kernels of the stories to come, set years ahead in situations considerably removed from that "five-mattress" hovel.

In a house that once provided temporary shelter for Christina’s family, fourth-grader Lucy and her friends are pressured into experimenting with their hardly-mature sexuality in “The Empty the Empty the Empty.” In “Our Mothers Before Them,” Annie – who was named by Christina while still in utero when the families shared the same 10-person room – narrates overlapping then-and-now stories, one from 1966 during China’s Cultural Revolution, the other in 1996 when an uncle arrives from China to pursue an American graduate degree. Another "five-mattress"-family becomes the focus of “The Evolution of My Brother,” in which Jenny who was separated from her parents when they were sharing the fateful overcrowded room, tells of her journey toward independence – made possible only by her parents’ sacrifices – as well as that of her nine-years-younger brother as he grows into almost-adulthood.

In “My Days and Nights of Terror,” a fourth-grade classmate of Lucy’s from “The Empty” recalls her “true FOB origins,” having arrived in the US less than two years earlier, and the challenges she faces navigating unfamiliar relationships, especially with another immigrant child who is more bully than friend. Zhang’s penultimate story features the last of the "five-mattress"-families in “Why Were They Throwing Bricks?,” and the generational conflicts that arise each time Stacey’s Chinese grandmother visits, causing divisions and alliances within the family.

That Zhang suffuses her young protagonists with autobiographical details – Shanghai-born, immigrant parents, New York-raised, Stanford-educated – adds authenticity to these narratives of strife, growth, and various degrees of success. Beyond the details, however, is a universal shared experience: a longing for home, and the challenges – economic, social, familial, cultural – to finally get there. The topic couldn’t be more timely as immigration debates continue to flare; with unblinking candor, Zhang illuminates the struggles to belong, to settle, to be welcomed home.

Terry Hong writes BookDragon, a book blog for the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center.