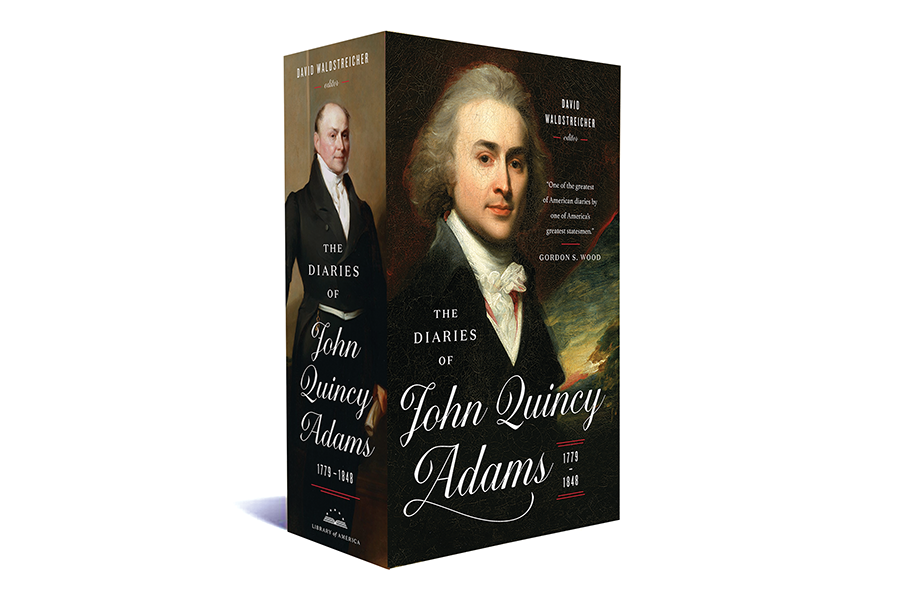

'John Quincy Adams' shares the diary of America's most passionate president

Loading...

John Quincy Adams, the latest entry in the prestigious Library of America collection, is a distinct treat, something long overdue for an attractive, accessible edition. It's the diary that John Quincy Adams kept for virtually the whole of his life, from 1779 when he was 12 years old right down to his death in 1848.

Adams, son of the country's second president, was active in public affairs for the whole of his life; he became US minister to the Netherlands in 1794, minister to Prussia in 1797, minister to Russia in 1809, minister to Great Britain in 1815, US secretary of state under President Monroe in 1817, president of the United States from 1825 to 1829, and then, most remarkably, nine consecutive terms in the US House of Representatives, serving from 1830 to the moment of his death in the Capitol Building. He traveled constantly, helped to draft dozens of key pieces of his fledgling country's diplomatic and legislative history, and fought an increasingly prescient battle against the institution of American slavery. It was a career crowded with three lifetimes' worth of activity.

And yet, that whole time, John Quincy Adams was keeping an extensive diary, and it's his greatest achievement. For decades, he kept up this tense, lavishly-detailed, shrewdly intelligent inner dialogue with the world as he encountered it. Like many prolific diarists, he would often fall behind – he'd make quick bullet-points as reminders, draw up outlines, and then, when time permitted, write up the day's events in full detail, often including long snatches of dialogue. Adams begins his diary entries during the American Revolution and keeps going through the war's conclusion, through the French Revolution, through the War of 1812, through the contentious administration of James Monroe, and through his presidency and his long term of service in Congress.

It's an astonishing sustained performance. Almost every entry over all those years bristles with concentration, but the really remarkable element of these diaries is their novelistic attention to atmosphere and personal detail. Readers don't encounter mere bare memos of events – they're again and again immersed in well-drawn scenes and vivid personalities. Adams displays a dramatist's ear not only for dialogue but also for pacing; crowded and hectic events are regularly offset by inventories, weather observations, financial notes, and the like.

We follow Adams from the press of business to the intervals of relaxation. From January 1831: “I spend about six hours a day in writing Diary – Arrears of Index – and Letters – I have given up entirely my Classical reading; and almost all other; excepting the daily Newspapers, and interruptedly a few pages of Jefferson's writings.… The Month has been of winter unusually severe; but my own condition is one of unparalleled comfort and enjoyment.”

Historian David Waldstreicher does an outstanding job editing this enormous mass of material, 51 manuscript volumes, almost 15,000 pages. In addition to superior workmanship – sewn binding and acid-free pages – the Library of America has always favored a light editorial touch, and Waldstreicher's End Notes are a perfect combination of helpful and unobtrusive. He gives interested readers a quick outline of the rather spotty publishing history of the diaries.

Adams's son Charles Francis Adams published a 12-volume edition in 1877, "Memoirs of John Quincy Adams," exercising his own ideas of what would and wouldn't interest the reading public. Allan Nevins brought out a 600-page one-volume selection from the "Memoirs" in 1928. But as Waldstreicher points out (in language perhaps unconsciously echoing the antique tone of the diarist), Charles Francis Adams's version of the diaries – leaving out “the details of common life” – inadvertently creates a dehumanized version of the writer. “By returning directly to the manuscript diaries and incorporating entries and passages excluded from the Memoirs,” Waldstreicher writes, “the current edition seeks to present a more rounded portrait than has heretofore been available to the general reader.”

It's an incredible job. Adams' original telegraphic punctuation is largely maintained rather than silently “corrected,” and reading these entries for hours on end is spellbinding. Adams observes everything around him with a shrewd and unblinking eye, constantly varying his focus from the intense and interpersonal to the broader and more reportorial. And some of the national politics Adams was dealing with two centuries ago feel startlingly contemporary. An entry from January 1820: “One of the most remarkable features of what I am witnessing every day is the perpetual struggle in both houses of Congress to control the Executive; to make it dependent upon, and subservient to them – They are continually attempting to encroach upon the Powers and authorities of the President.”

This year marks the 250th anniversary of John Quincy Adams's birth, and now, thanks to the Library of America, readers seeking to know the mind and heart of the most intelligent, most prickly, and most oddly passionate man ever to be President of the United States have an invaluable resource that actually looks good on the shelf. In these pages John Quincy Adams lives and breathes and notices everything.