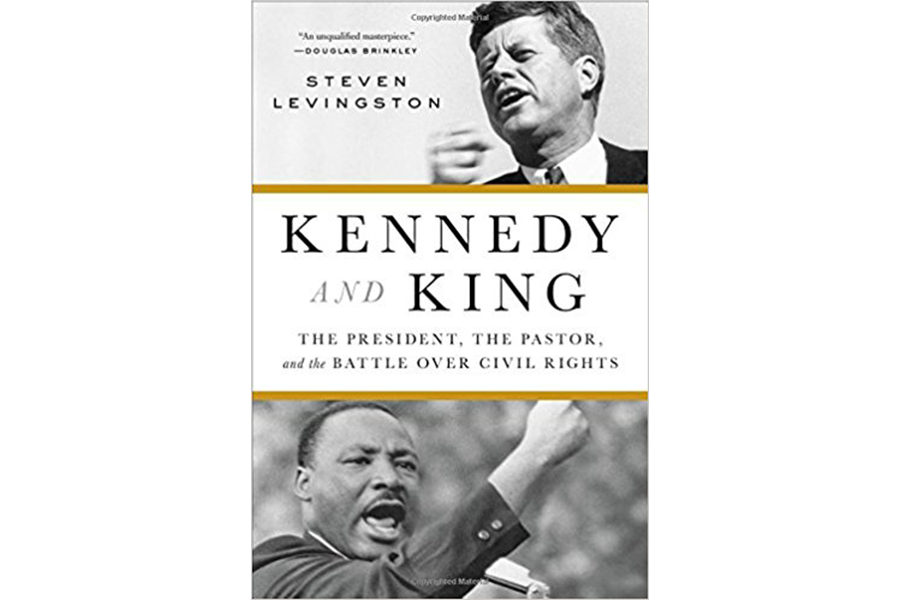

'Kennedy and King' portrays two giants of 1960s America

Loading...

Washington Post nonfiction-book editor Steven Levingston's newest book, Kennedy and King: The President, the Pastor, and the Battle Over Civil Rights, works very hard to portray a meeting of minds, a converging of world views, and not incidentally the fast-step maturation of a President's social conscience. It portrays the two most powerful and charismatic men in America in the 1960s, President John F. Kennedy and civil rights leader Martin Luther King, and for long segments of its narrative, the book is therefore telling parallel but unconnected stories.

The stories are familiar in their separate tracks: King making immortal speeches, fervently advocating non-violent protests against the evils of segregation and racism plaguing America, and Kennedy entering Congress, campaigning for the White House, and then as President grappling with an enormous range of issues.

Levingston's writing on King is unfailingly perceptive and eloquent, looking clearly at his flaws (mainly vanity, and a penchant for histrionics that's endemic to Southern preachers, even Boston University-educated ones) while conveying on every page his greatness. The main problem with the book is that its story is lopsided: in these pages, King has both the vision and the courage to pursue it in the face of all obstacles. Kennedy, on the other hand, presents an imbalance not even the most sympathetic writer can fully right.

Jack Kennedy never had a black friend in his life. He scarcely even met a black person until he was in his twenties. In his whole life, he never dealt on a regular, repeated basis with any black person who was not his servant. It's true – and Levingston notes the instances – that he was open-minded on race questions to a greater extent than most men of his generation, and it's true that when government patronage was in his gift, he was generous to black applicants.

But despite his sporadic frustration with the deep-grain racism of the South (what Levingston refers to as “a quiet stiffening of his will to take on the brutal and archaic practices of the South”), he viewed all proposed civil rights legislation with the fishy eye of a career politician. He sat on measures that would have had incalculable moral impact on America's minorities – including measures urged by King himself – because he worried that they'd cost him votes in Southern districts he was anxious to please. As president, he could have brought most of King's vision great big leaps closer to being reality, but he didn't do it, because it wouldn't play well in Chattanooga. Levingston quotes King saying that it's difficult business to educate a president. Maybe so, but it's also true that Jack Kennedy, unlike his brothers Bobby and Ted, wasn't a particularly eager student.

Civil rights lawyer Joseph Rauh, in response to JFK's rather tepid attitude toward the noxious Senator Joe McCarthy and his anti-Communist witch-hunts, commented: “A man who does not believe in the civil liberties of white citizens cannot be trusted to stand up for the civil rights of Negro citizens.” And King's own remark about Senator Kennedy were something less than effusive: “I hold Senator Kennedy in very high esteem,” King said. “I am convinced he will seek to exercise the power of his office to fully implement the civil rights plank of his party's platform.”

When Kennedy looked at the growing discontent among black citizens in cities throughout the South, he was usually concentrating less on King's rhetoric of passionate social change and more on comments like the one Malcolm X made after police dogs were set on black protestors in Birmingham: “We believe that if a four-legged dog or a two-legged dog attacks a Negro he should be killed. We only believe in defending ourselves against attack.” JFK wanted to use King to help maintain order at least as much as King wanted to use JFK to advance his cause.

Levingston is aware of this uneasy dialectic, of course, and he treats it with the complexity that it deserves. His version of JFK is a man whose pragmatics are constantly at war with his idealism, and thanks to Levingston's impressive narrative skills, the spectacle of this president confronting the most divisive issue of his day is consistently fascinating. And Levingston saves one of the best anecdotes of that struggle for the book's end: the March on Washington has fetched up hundreds of thousands of people almost across the street from the White House, and JFK is watching from a mansion window with long-time White House doorman Preston Bruce (author of the thoroughly enjoyable memoir "From the Door of the White House"). As Levingston puts it, “this son of a sharecropper stood with the president of the United States listening to the crowd below singing 'We Shall Overcome.' Years later, Bruce recalled that an emotional John Kennedy gripped the windowsill so firmly his knuckles blanched. 'Oh, Bruce,' he told the doorman. 'I wish I was out there with them.'”

Bruce recalled that moment nearly 20 years later, and the three other men who were there at that windowsill don't appear to have heard the president say such a revealing line. But it's nice to think it.