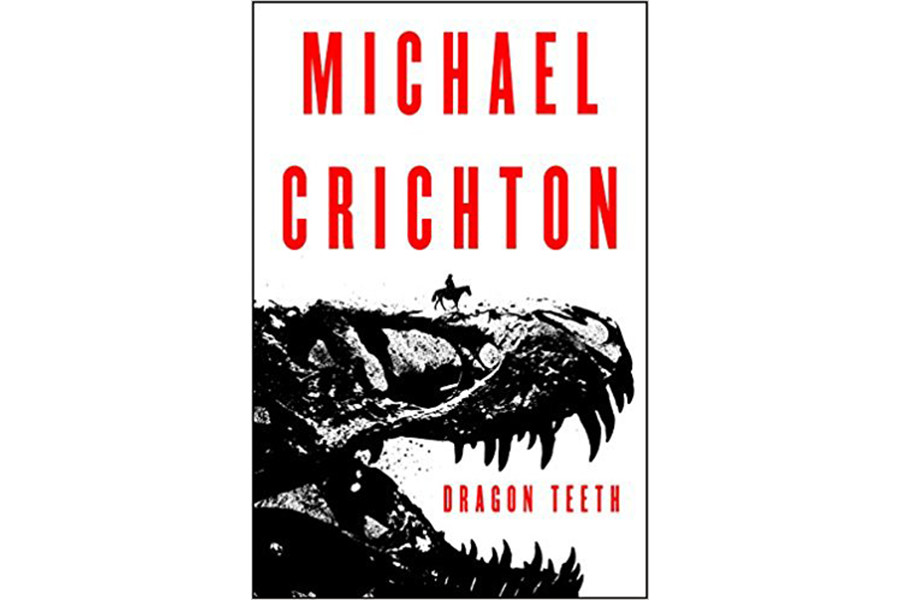

'Dragon Teeth' – the latest posthumous Crichton book – is propulsively readable

Loading...

Of the many time-honored literary gimmicks that fill Dragon Teeth, the new posthumous novel by Michael Crichton, the first is the woolliest and most amusing of them all, the bald-faced announcement by Crichton's widow Sherri that the book's complete manuscript was found among her husband's papers long after his death in 2008. “After reading the manuscript,” she tells readers in a brief Afterword, “I could only describe Dragon Teeth as 'pure Crichton.'” '

The book is Crichton's third posthumous publication, following 2009's "Pirate Latitudes" and 2011's "Micro." Readers are of course free to believe whatever they like, but if there are readers who actually believe that not one, not two, but three manuscripts by one of the world's best-selling authors were just sitting in his hope chest patiently awaiting discovery and periodic distribution to the world, well, they might also be interested in a great one-time-only deal on a certain bridge in Brooklyn.

But that Afterword is completely correct on one point: "Dragon Teeth" is indeed “pure Crichton” (which Crichton is a question we can leave for future literary critics to answer). The novel is a lean, propulsively readable adventure story, filled with seamlessly-interwoven exposition and sharp dialogue. It's easily the best thing with Michael Crichton's name on it since 1999's "Timeline."

Much like that 1999 book, "Dragon Teeth" spurns the usual Crichton formula of extrapolating the cutting edges of contemporary science and instead looks to the past for its narrative energies. The story is set in 1876, when two conflicts were raging throughout the chaotic and wide-open spaces of the American West. The first of these conflicts was enormous: the protracted Indian Wars between the US Army and the Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Crow, and other tribes resisting the westward expansion of the United States.

The second conflict was much more localized but struck its combatants as no less fierce: the celebrated “bone wars” between rival pioneering paleontologists Othniel Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope. These two men, accompanied by teams of more-or-less willing students, stuck out every summer for the badlands of the Wild West in search of dinosaur fossils. “Cope and Marsh knew exactly what they were about: they were discovering the full range of a great order of vanished reptiles,” "Dragon Teeth" tells us at one point. “They were making scientific history.”

The order of vanished reptiles, first named by Richard Owen in 1841, was of course Dinosauria, and linking the word “dinosaur” and the name “Michael Crichton” is about as sure-fire a recipe for magic as the modern publishing world can muster.

The book dramatizes the story of the rivalry between Marsh and Cope and presents the whole exciting saga through the viewpoint of an initially callow Yale undergraduate named William Johnson, who lies his way into Marsh's next expedition in order to win a bet. Johnson is subsequently suspected by Marsh of collusion with Cope (whom he considers “little better than a common thief and keyhole-peeper”), left behind by Marsh and his team in the town of Cheyenne in the Wyoming Territory, and taken in by none other than Cope himself, who assures him, “I'm not the monster you have heard described. That particular monster exists only in the diseased imagination of Mr. Marsh.”

Johnson's journey continues, and the timing could scarcely be worse: While the expeditions are en route to their destination, the news explodes across the country that General George Armstrong Custer and his Seventh Cavalry have been massacred at Little Bighorn, and that native tribes throughout the West are more dangerous than ever. Cope is told that his planned venture into the Crow hunting grounds in the Judith River basin would be suicide: “The Crow are usually peaceable, but these days they'll kill you as soon as look at you.” And some dangers range much closer to home: the rivalry between Marsh's men and Cope's quickly heats up to potentially lethal levels of competition.

Along the way, "Dragon Teeth" delivers the science behind its dramatics with positively contagious energy. Between them, Cope and Marsh discovered well over 100 new species of dinosaur and helped to establish the fledgling science of paleontology, and in page after page of straightforward, highly readable prose, the book conveys the sheer wonder of those early days. Young William Johnson meets an array of famous walk-on characters from General Phil Sheridan to Robert Louis Stevenson to Brigham Young to Wyatt Earp, and there are ample moments where the headlong plot pauses for evocative scenes, as when Johnson, Cope, and their team are caught in a thunderous nighttime buffalo stampede. “They eventually could see nothing, and could only listen to the thundering hooves, the snorting and grunting, as the dark shapes hurtled past them, ceaselessly,” readers are told. “It seemed as if they went on forever.”

“Othniel Marsh was always good copy,” a character snidely comments at one point in the book. The same can also be said about the appearance of any new book under the Michael Crichton byline. These Crichton fossils being unearthed with such regularity are archeological gold.