'Thunder in the Mountains' recounts the tragedy of the Nez Perce War

Loading...

In the spring of 1873, a Nez Perce Indian known as Chief Joseph tried to persuade two officials of the American government that they were illegally permitting white settlers to trespass on his tribe’s traditional lands. The officials claimed that Joseph was bound by an 1863 treaty that ceded his rights to Oregon’s Wallowa Valley, where Joseph’s tribe had been seasonally hunting and fishing for hundreds if not thousands of years. But Joseph had never acknowledged the legitimacy of this treaty, and he offered a simple analogy to help the officials see the injustice of their case.

The treaty, he said, was equivalent to a white man telling him, “Joseph, I like your horses, and I want to buy them.” After being told that Joseph did not want to sell his horses, the white man paid Joseph’s neighbor for the horses. “The white man returns to me and says ‘Joseph, I have bought your horses, and you must let me have them.’ If we sold our lands to the government, this is the way they were bought,” Joseph explained.

The officials, remarkably, were persuaded, and the secretary of the interior gave Joseph and his band permission to stay in the valley. The government even promised to set the land apart for the exclusive use of the Nez Perce by buying out the current settlers and preventing more from staking claims. This was a very unusual response in the 19th century: The US government was taking seriously the legal rights of Native Americans and treating them justly.

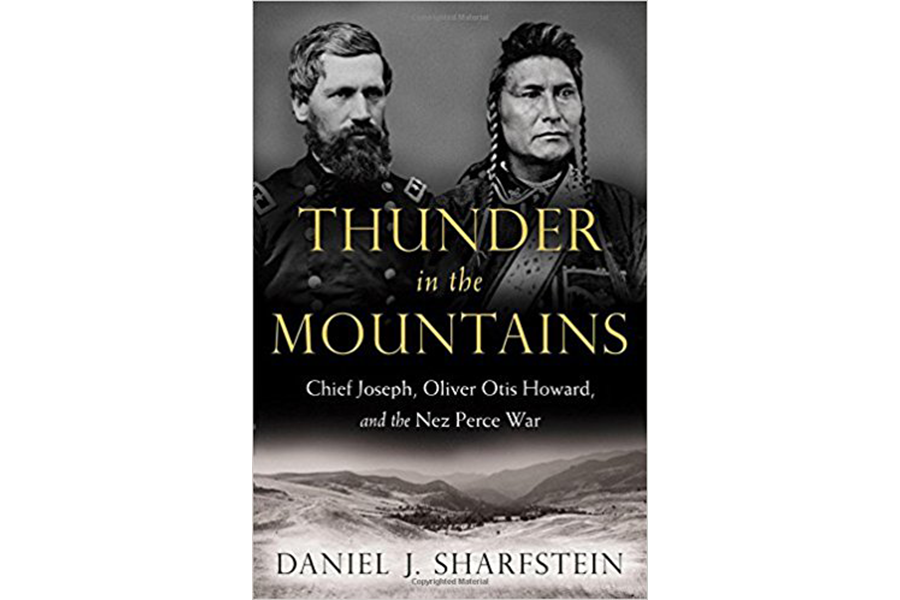

Only four years later, a brutally violent war between the Nez Perce and the US Army claimed hundreds of lives. The remnants of Joseph’s band were forcibly moved onto a distant reservation, and the Wallowa Valley was settled exclusively by whites. How and why this dramatic reversal occurred is the subject of historian Daniel J. Sharfstein’s magnificent and tragic new history of the conflict, Thunder in the Mountains: Chief Joseph, Oliver Otis Howard, and the Nez Perce War.

Oliver Otis Howard was a former union Army general with a dubious past. Despite being widely criticized for incompetence during the Civil War, he was appointed to run the Freedmen’s Bureau during Reconstruction. He did oversee some useful initiatives to help former slaves – he helped found Howard University – but he also embezzled public funds and caved to pressure from ex-Confederate politicians who opposed land grants for former slaves. His appointment to administer territories in America’s Northwest was something of a banishment.

After meeting with Chief Joseph, however, Howard was initially convinced that it would be a serious mistake to confiscate Nez Perce lands. Joseph was not only a powerful and spellbinding orator, his argument was legally and morally unassailable. But a variety of reasons soon motivated Howard to retreat from his support for Joseph – political and economic pressure from local settlers, personal vanity and ambition, and an entrenched prejudice that the nomadic lifestyle of the Nez Perce was inferior to the sedentary ways of white farmers.

Joseph was a tireless and patient negotiator, and Sharfstein emphasizes how thoroughly committed to compromise within a legal framework Joseph remained, even as the reversals and lies of government bureaucrats and distant politicians multiplied. At the far reaches of American territory, the government was both too weak and too strong. Its power was conveniently inadequate when the defense of the land and rights of native peoples was necessary. But when white settlers perceived a threat to their lifestyle, the military might of the government was deployed to compel tribes to move onto reservations.

Joseph and his tribe posed no threat to white settlers. They simply asked for the same equal protection of the laws that the recently passed 14th amendment ostensibly guaranteed to all citizens. When this request was denied, they were still prepared to move peacefully to a reservation, and full-scale war was caused only by a massive overreaction from Howard and his superiors.

Sharfstein is a wonderful storyteller with a deep knowledge of all the relevant source material from the period. His narrative is rich with fascinating historical details – a fancy San Francisco hotel that only takes payment in gold, a scout for the US Army who compares the blisters on his feet to watermelons, a Nez Perce warrior who compares the lead bullets flying during battle to a swarm of bees. The war was covered avidly by contemporary newspapers, documented in letters and memoirs by troops and generals, and recounted in speeches and interviews by multiple Nez Perce warriors. All of this comprises a rich archive of primary source materials that Sharfstein has mined to brilliant effect.

However vivid the material and well-structured the narrative, the story is inescapably tragic and often painful to read. It’s a powerful reminder that Americans live on lands stolen by force and without provocation. It’s also a tantalizing glimpse of a possible future that never materialized. While the American government essentially presented Native Americans with a choice between assimilation and annihilation in the 19th century, Joseph imagined a third alternative – equal treatment and legal standing for tribes that chose to pursue a traditional lifestyle. But as Joseph and his tribe learned through years of mistreatment by agents of the US government, equal protection under the law was just an American myth.