'Olive Witch' is the memoir of an outsider on a quest for belonging

Loading...

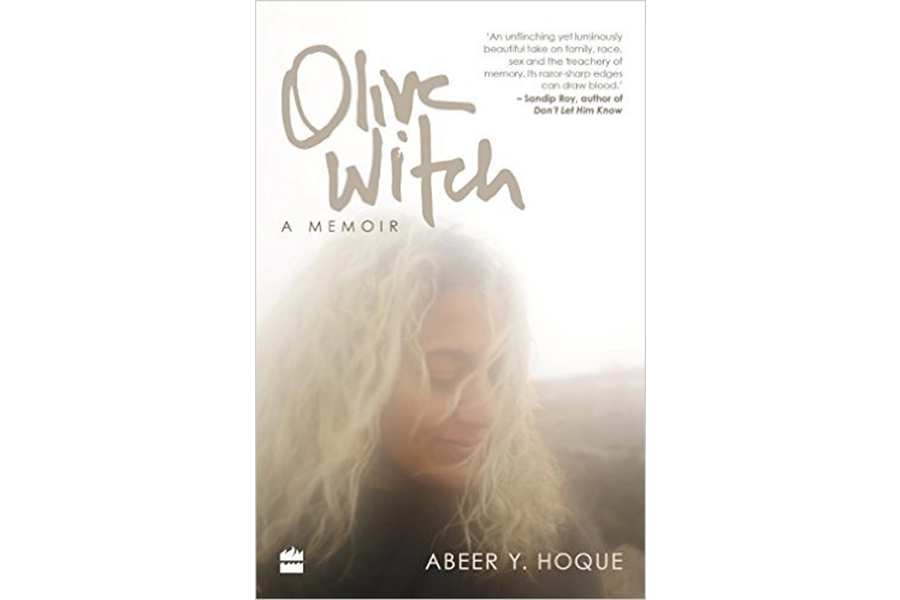

“bow echo,” the very first words of Abeer Y. Hoque’s raw, unblinking, urgent-in-these-times memoir, Olive Witch, is an easy-to-miss clue. Followed by a temperature (73°F) and what looks like a diary entry, the two words might be mistaken for a place name, easily glossed over. It proves, however, to be a subtle warning: a “bow echo” is a meteorological term, according to the Oxford Dictionary, referring to “a bow-shaped radar signature associated with fast-moving storm systems accompanied by damaging winds.” Hoque’s ‘fast-moving’ life story is about to embark, opening with the resulting "damage" from a suicide attempt.

Born in Nigeria to Bangladeshi parents, Hoque is the oldest of three children birthed on three different continents – her sister in Bangladesh, her brother stateside. For 13 years (except for a brief Pittsburgh layover), Hoque is an “onyocha” – a foreigner – in Nigeria where her father is a University of Nigeria professor in Nsukka and her mother a girls’ school economics teacher. While she envies the dark skin of the local children, she is at least grateful for not being one of the “half-castes ... the only ones who have it worse than the foreigners. The foreigners can’t help being foreigners, but being half-Nigerian is like being a traitor.... I want all or nothing. It might be too hard to almost belong. Not belonging, on the other hand, is cut and dried, an easy place to find.”

With each family move, that "not belonging" becomes more difficult. When the family migrates to Pittsburgh, Hoque’s transition initially seems smooth: “[w]ithin six months, no one [can] tell that I didn’t grow up in middle America.” Despite “some confusion about how much of this American life [the Hoque children] are allowed to absorb” in between parent-mandated Islamic school on Sundays and eating Bangladeshi food at home, Hoque adapts to the intricacies of teenage slang, overcomes her “odour fears” with deodorant her mother insists she doesn’t need, discovers public libraries, and joins the swim team. Yet isolation looms: “Outside our sunlight-deprived house is a neighbourhood that hasn’t yet accepted us, nor have we accepted it. Four years and I’ve not been in any other house on our street except our own.”

"'I can’t wait,’” she writes repeatedly in her journal. “College. I cannot wait to leave home. I’ve been ready for years.” When Hoque arrives at the University of Pennsylvania, she decides, “I’m going to be bold.” Her four years of high school silence are over: “I imagine I have a superpower. I will have what I want, I will take what I want, and most of all, I will say what I want. I will engage instead of watch.” Her first conquest – and first love – is Glenn, a classmate she meets and claims at orientation; he sings her a Rage Against the Machine lyric that inspires the titular “Olive Witch.” “I make it my niche,” Hoque insists, “I tell the truth sooner, no matter how alone and exposed it makes me feel.”

Hoque’s stalwart intellect continues to propel her forward, placing her in a prestigious graduate program at Wharton. But parental, cultural, even academic pressures eventually overshadow her chameleon-like ability to “put on any face with its matching mood and modulation.” Adaptability devolves into “I can’t tell if I exist anymore,” until she swallows 32 pills and wakes in a Philadelphia psychiatric ward. Hoque’s second-chance rebirth launches her peripatetic search for that ever-elusive sense of belonging, pausing in San Francisco where she learns to write herself into existence, stopping in Bangladesh where she discovers her authorial legacy, and continues onward in her quest for creative agency.

Originally published in 2016 in India, "Olive Witch" was over a decade in the making, a jigsaw puzzle created piece by piece until the narrative became whole, not unlike its creator. The seven “bow echo” vignettes that capture Hoque’s day of (re-)awakening from early morning to late evening, began as a one-act play performed in 2002; interspersed throughout the book’s 250-ish pages, the vignettes provide a skeletal structure, into which Hoque fleshes out her journey from "We’re here to help you" to "You’ll be okay." That a dozen chapters were published previously as standalone excerpts, essays, and stories in various publications (one excerpt won a 2009 Commonwealth Short Story Prize) intermittently comes through, with the occasional unnecessary repeats. Small missteps notwithstanding, “Olive Witch” is ultimately an encouraging, timely story for the masses, an inspiration to live – authentically, globally, with urgent immediacy.

Terry Hong writes BookDragon, a book blog for the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center.