3 new Obama biographies by unabashed supporters

Loading...

“There is a period in the advance of any great man's influence between the moment when he appears and the moment when he has become historical, during which it is difficult to give any succinct account of him,” wrote the critic John Jay Chapman a century ago. “We are ourselves a part of the thing we would describe.”

Chapman was writing about the poet Robert Browning, then at the height of his fame. But the warning applies universally, and maybe never more sharply than when attempting to assess the place in history of an outgoing US President months or even mere weeks after he leaves office. The situation is rendered all the more difficult in 2017, since the outgoing President, Barack Obama, was the nation's first black president and also (not coincidentally) the object of unremitting resistance from an obstructionist Congress.

Social, economic, and educational divisiveness is worse in America than it's been in a century, and the departure of President Obama from the national stage in January consequently feels far more ominous than the usual administrative change-over. There's the strong sense of a brief era ending.

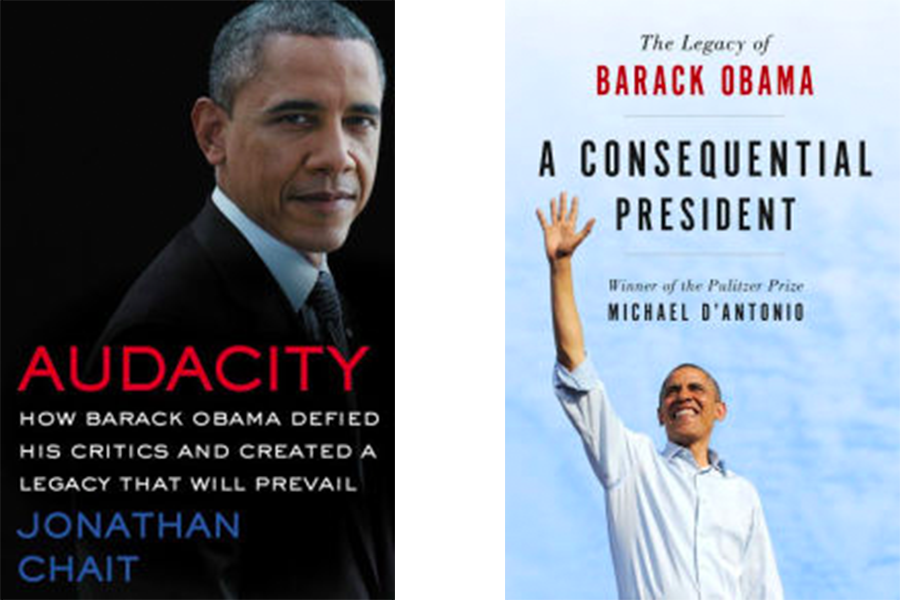

This will produce a bumper-crop of books analyzing the Obama administration, and as in all cases, these will happen in three waves: participant memoirs (including the President's own, likely to be a classic of the genre), partisan takes, and finally, once the dust settles, disinterested historians. These three books – Jonathan Chait's "Audacity," Michael D'Antonio's "A Consequential President," and Michael Days' "Obama's Legacy," all belong to the second group, the partisan takes. All three are written by unabashed Obama supporters, and all three attempt to take distanced, impartial views of social and political struggles about which their authors are not the least bit impartial.

They all have the same basic story to tell, naturally: the nation's 44th president taking office against the most openly stated across-the-board Congressional opposition any president had faced in a generation. These Congressmen, as Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Michael D'Antonio puts it, “would distinguish themselves as staunchly opposed, even in a losing cause, rather than dignify the president's ideas with even the slightest support.”

Philadelphia Daily News editor Michael Days echoes this point: “Obama's accomplishments have come against a backdrop of criticism or open defiance from conservatives, lack of cooperation in Congress, and racially tinged commentary” and goes on to list some of those accomplishments: “the passage of the Affordable Care Act and the Supreme Court's upholding of it, the legalization of same-sex marriage, and, dare I say, ridding the planet of one Osama bin Laden.” Journalist and author Jonathan Chait assures his readers that President Obama “accomplished nearly everything he set out to do, and he set out to do an enormous amount.”

This note of aggressive pre-emptive triumphalism is common to all three books. All three of these authors believe what D'Antonio writes, that history will view President Obama as “a transformational president,” and they line up the same key achievements of the Obama administration: stabilizing the US economy in the wake of the Great Recession, saving the auto industry, providing a large economic stimulus package, overseeing a prolonged period of economic growth, advocating increased civil rights for previously marginalized citizens, significantly reducing US military presence in Iraq and Afghanistan, and even the controversial nuclear treaty with Iran, which is referred to as the high point of Obama's foreign policy efforts.

Indeed, Obama's foreign policy is the main subject of Derek Chollet's new book "The Long Game: How Obama Defied Washington and Redefined America's Role in the World," where readers are told that Obama “prizes deliberation, is comfortable with complexity and nuance, and is deeply skeptical of decisions driven by passion.”

Obama was the first candidate since Eisenhower to win more than 51 percent of the popular vote two times in a row, and his administration is viewed by all of these writers as an ethical high point in modern politics, an eight-year period without personal scandals or the shadow of impeachment. All three of these books work hard to make their cases to court of posterity, and each is convincing in its own way. These authors' youngest readers will likely live to see what posterity makes of legacy being debated here, and in the meantime, we can try not to put too much weight on the fact that nobody reads Robert Browning anymore.