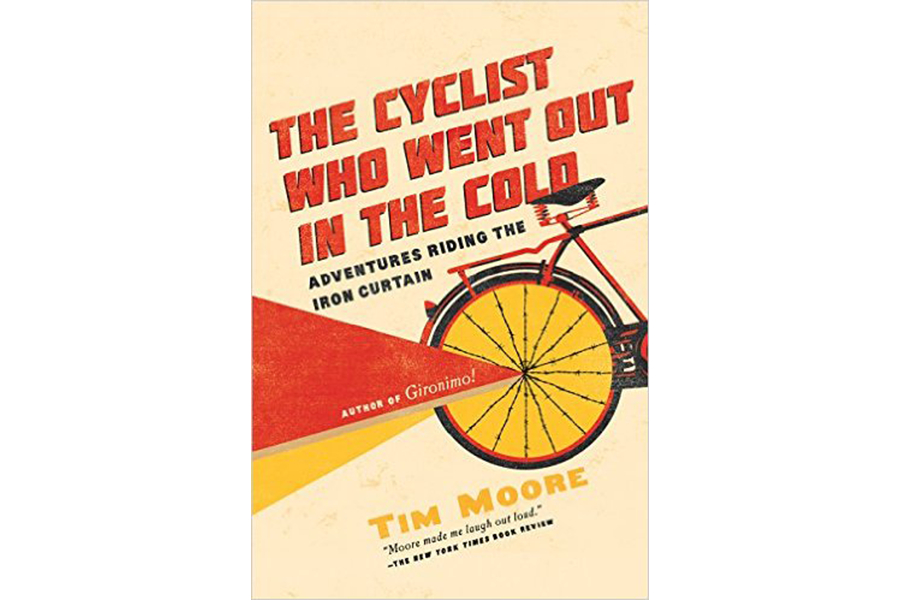

'The Cyclist Who Went Out In the Cold' rides the Iron Curtain Trail

Loading...

People stared in bewilderment at Tim Moore as he biked the border of former Eastern Europe, along the Iron Curtain Trail. I would have too.

Mr. Moore complicated this already monumental journey by peddling a small-wheeled East-German shopping bike, rather than something practical. And he risked freezing himself solid, into a communist-era worker-hero statue, by beginning his trip in arctic Scandinavia, in winter, traveling south.

Definitely, this made for colorful incidents on which for Moore to riff; he’s a British travel writer who has published nine other humorous books about challenging trips he’s made, including one where he traveled around Spain leading a donkey, using a 12th-century handbook.

But sometimes there’s too much going on here at once in The Cyclist Who Went Out in the Cold: Adventures Riding the Iron Curtain. (Some readers also may be baffled by his British slang.)

Moore is very funny. Regarding bicycling conditions in Finland he comments “[I]f there’s one thing guaranteed to make you sweat like a pig, it’s the knowledge that doing so might kill you.”

And he provides vivid descriptions. He talks about Finland’s “bleak refrigerations of forest and frozen water [and] depthless horizons of spruce-girdled white lakes.” He’s also very good with history, including a description of the Winter War when, in 1939-1940, invasion by a well-equipped Soviet Army was stymied for months by much smaller but infinitely smarter Finnish forces.

However, I found myself not always happily distracted from a route with an over-abundance of fascinating sites and culture by questions like whether Moore will find a place to stay for the night in -14 C Finland, or if, instead, this a manuscript someone found on his frozen body.

Nonetheless, there’s a lot to love here, including the novelty of the route: The Iron Curtain Trail is a 10,000-km ride through 20 countries along what was the world’s most extensive expression of divisive hostility. Moore peddles past innumerable vestigial guard towers and other ghostly reminders that wandering from East to West could earn you a bullet in the back.

Finally, on the road from Helsinki to St. Petersburg, Moore submits to Russian border control and crosses for the first time to the other side. Welcoming him is “a stern woman with magenta hair and jarringly vivid make-up” who scans his documents with “a look of incredulous outrage...” but then lets him in.

“After 1,700 km of odourless, aseptic Finland”... Russia “stank.” Meanwhile, its drivers traveled at “terminal velocity and every blind corner was a cue for urgent overtaking.”Moore has few kind words about Russian scenery, either, and describes biking “past factory chimneys cheek by smutty jowl with gilded Orthodox domes.”

So, with relief, it’s into the Baltic countries – Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. He muses: “[For] more than half of my life ... the simple act of riding a bike [here] would have had me imprisoned and very possibly killed on sight.”

Here is what Moore says about Tallinn, Estonia’s capital city: It “felt like some overcrowded Brothers Grimm theme park. The old town’s tilting cobbled alleys were thick [with tourists] gawping up at Rapunzel towers and Pied Piper gables....”

But there’s much of Russia in these countries, which spent decades under Soviet control, and had large numbers of Russians poured in to dilute native populations. In Latvia, “The first town .... was dominated by a towering Mother Russia war memorial, and the now-familiar trappings of totalitarian infrastructure....”

The centerpiece of Moore’s route is the portion along the inner German Border – where Germany was split between East and West. Moore augments with exceedingly interesting recollections from a visit 25 years earlier when the Wall had just fallen.

The Germany route “forever criss-crossed the old border, but I rarely lost my bearings. The West had better tarmac, fewer cobbles, more bike paths ....." Moore liberally seasons with Stasi history and tales of attempted escapes.

As Moore approaches his final destination – Tsarevo, Bulgaria, at the Black Sea – he serves further helpings of battles with weather, rough trails, and dodgy food and accommodations. And he gives fly-by observations of the remaining border countries, which include the Czech Republic, Hungary, Serbia, and Romania.

“Cyclist” could easily have been 500 or more worthwhile pages if Moore had wanted to burrow deeper into cultures he freewheels past all too quickly. Nonetheless, Moore is a quick and keen observer. His wit is a consistent pleasure. And this “in the cold” travelogue is an extraordinarily audacious and absorbing venture.