'Hero of the Empire' wonderfully recreates the epic of a young Churchill

Loading...

Winston Churchill often and infamously maintained that he didn't worry about the verdict history would pass on him, because he intended to write his own history. He and his stable of paid ghostwriters were so feverishly active over the many decades of Churchill's public life that the boast has very nearly proven true. The hallmarks of the Churchill legend that began with Churchill's own pen are as well-known as anything in 20th-century caricature: the heroic youthful exploits in the sprawling empire of Victorian and Edwardian England, the meteoric rise in politics, the career as First Lord of the Admiralty during the First World War, the legendary Prime Ministership during the Second World War, the stirring loquacity, the bulldog tenacity, and so on.

There's an undeniable entertainment factor, when great figures in history craft their own legend, and it's arguable that no such figure – not Martin Luther, not Casanova, not the Marquis de Sade – has ever been as successful at it as Churchill was. But there's also an attending danger, since the first duty of the true historian is to discard legend in favor of fact.

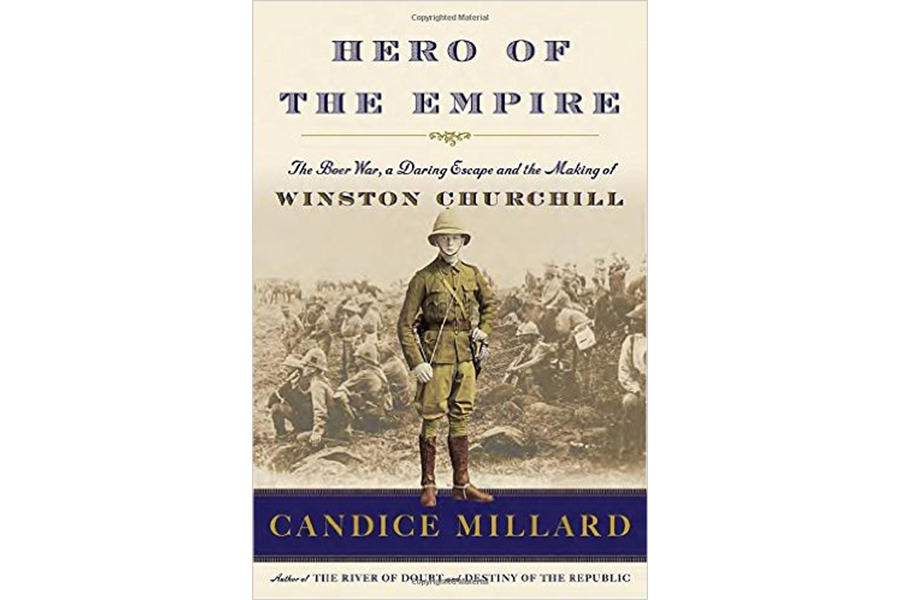

This makes books like the latest from Candice Millard, Hero of the Empire: The Boer War, a Daring Escape and the Making of Winston Churchill as valuable as they are entertaining; Millard sets out to tell in clear and readable detail the real story of one of the earliest dramatic events in Churchill's life, his capture and imprisonment while in Africa in 1899 covering the Boer War as a journalist for The Morning Post, his subsequent escape, and the political capital these things earned him at the very beginning of his career. Churchill's own 1900 book recounting his adventures, "From Ladysmith to London via Pretoria," is a fairly gripping page-turner.

This literary competition from her subject is nothing new for Millard, whose 2005 bestseller "River of Doubt" told the story of former President Theodore Roosevelt's 1913 expedition deep into the Amazon, a story Roosevelt himself told superbly well in his 1914 book "Through the Brazilian Wilderness." Once again, Millard writes her book in the shadow of the very person most concerned with trying to shape the record of events for posterity.

Her account of Churchill's Boer War adventures might have made the great man wince at times. She deals with the war itself skillfully, assuming from the start that her readers won't know its details. And she's likewise thorough in charting the earlier exploits of young man Churchill, the scion of an ancient noble house with a grand name and grand relatives but no grand income.

Millard tells us that from his earliest years, he had been 'fascinated by war,” but her account makes it clear that his real fascination – an itch, a compulsion that never left him – was fame. While still in his teens, Churchill began seeking fame in the easiest way the age provided: scraping up the necessary money and connections, he went wherever in the Empire there was military action, from Cuba to India to Africa. He'd attended the Royal Military College at Sandhurst, but he went to these various theaters as much as a freelance journalist, although he often tended to forget this and act the soldier.

This was the case with South Africa in 1899, where Churchill and the troops he was accompanying on a mission were captured by the Boers and imprisoned. Churchill protested his observer status, but as Millard drily puts it: “In his eagerness to escape imprisonment, however, Churchill had forgotten one critical detail: He had been in full view of the Boers during the attack, and they knew that, even if he was a civilian, he had acted as a combatant.”

That imprisonment and Churchill's escape – he scaled a wall, left his fellow prisoners behind, and managed to hide from the Boer authorities successfully as he made his way across hundreds of miles of enemy territory to the safety of the British lines – is the heart of "Hero of the Empire," and Millard often, perhaps too often, hits a tone of high melodrama scarcely distinguishable from Churchill's own account. About an earlier military adventure in the Hindu Kush, for example, Millard writes, “The fact that he was wrapped in a dead man's blanket – bought just weeks earlier from the possessions of a British soldier killed in these same mountains – only seemed to complete the ominous tableau.”

But her general narrative instincts are as true here as they've always been, and she keeps constantly in mind what Churchill himself kept constantly in mind: not the heroism of British troops nor the doomed bravery of the Boers but rather the fame of Winston Churchill. In many ways, the story of his imprisonment and escape was the political making of the man – certainly Churchill himself thought so, and his future self would display the same characteristics Millard brings so vividly to life in "Hero of the Empire": opportunism, a small dash of very tactical bravery, and a ready pen.