'Riverine' is the memoir of a writer who cannot slip free of her past

Loading...

Over the past several years, a new kind of book has emerged, what we might call the Essayistic Memoir.

Such books proceed loosely, associatively, wandering from life event to cognitive science to feminist theory and back again. In books like Maggie Nelson’s "The Argonauts" and Eula Biss’s "Notes from No Man’s Land," we are left less with the arc of a life than with a vision of how an intelligent, omnivorous mind negotiates a life. In doing so, these books resemble the work of the original essayist, Montaigne. They aren’t so much creating a genre as returning a genre to its roots.

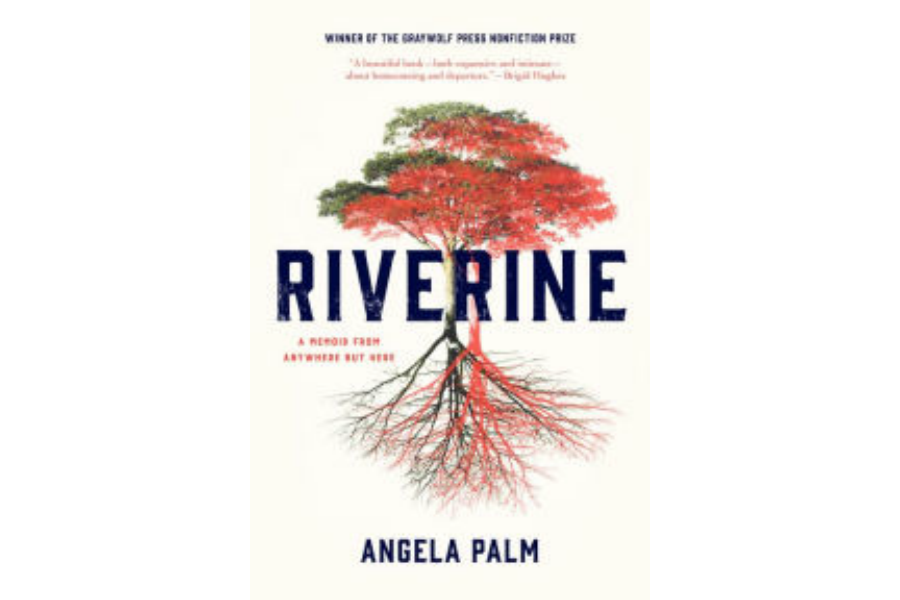

Angela Palm’s Riverine: A Memoir from Anywhere But Here, winner of the Graywolf Press Nonfiction Prize, is the latest example of the Essayistic Memoir. It’s an interesting story about an interesting (if still very young: Palm is in her 30s) life. But this life really serves as an intellectual provocation, a spark that gets Palm thinking about other things: geography, thermodynamics, prison privatization. "Riverine" is, in Palm’s words, a “braided essay … read[ing] like the inside of a mind.”

Palm grew up in a rural Indiana town that “had once formed the bed of the Kankakee River." Now, thanks to the Swamp Land Act of 1850 and the rerouting it called for, the area is frequently flooded farmland, a place “beyond limits, isolated and insular.” Even though Palm has a complicated love for her riverine Indiana, even though she feels claimed by its mud and corn and skies, her book is largely a narrative of escape: Palm grows up, moves to the more liberal Vermont, and becomes a writer. A new landscape allows for a new life. Or, as Palm puts it, “Place as reboot.”

All of this is well done, though the story – a writer leaving home and finding herself as a writer – is also well worn. What differentiates "Riverine," though, is two-fold. First, Palm is a particularly good observer of class. Early on, she remarks upon the differences between her town’s “affluent Dutch," the desperately poor, and her own family, somewhere in-between: “The clothes were usually one season removed from fashionable, but they were new and our very own.” Few American writers are attentive enough to class and its determinative power. Palm is one of them, her book filled with sharp analysis of the relationship between place, social status, and ethos.

The second distinctive quality is Palm’s description of her relationship with Corey – a slightly older and much loved childhood neighbor who falls into petty crime, hard drugs, and, at the age of 20, double murder. When she was eight, Palm writes, she “imagined mapping myself onto his skin, clinging to the idea of a future between me and my eleven-year-old friend that did not exist.”

Later on, the two flirt and kiss, but any future together is erased after Corey is imprisoned for life. As she grows older, Palm continues to worry over him, asking how a life could turn out so wrong, providing mini-essays on criminal etiology – drugs and upbringing explain much but not all – and the inefficacy of prison as a deterrent. Eventually, now married with two children, Palm decides to reestablish contact with the imprisoned Corey, first writing then visiting.

It’s a strange and generative relationship, leading to some of Palm’s best writing and thinking. After visiting Corey, Palm describes the cosmological theory that the “beginning of time sent matter expanding in two directions, rather than one,” creating the universe we know (“time’s one-way arrow”) but also another, parallel universe, one that “would have expanded in the opposite direction.” By this view, time “has one past but two futures.” What a perfect way to describe how Palm’s actual life has been haunted by a counter-life, a life where Corey became not a murderer but a husband and father.

Unfortunately, Palm’s relationship with Corey drops away for long stretches, and the pages devoted to Palm’s struggles as a 20-something in Indianapolis and her decision to become a writer in Vermont drag considerably. In describing the kind of essay writing she most admires, Palm proudly declares, “I embrace complication.” To which the reader might respond, there’s complication and then there’s complication; there’s productive looseness and then there’s distracting looseness.

We’re in a moment where the most celebrated essayists are often the most digressive. This is mostly to the good. But knowing where your writerly strengths lie and staying close to them is a skill, too. "Riverine" is a strong first book. With a little less wandering and a little more rootedness, Palm’s next book should be even stronger.