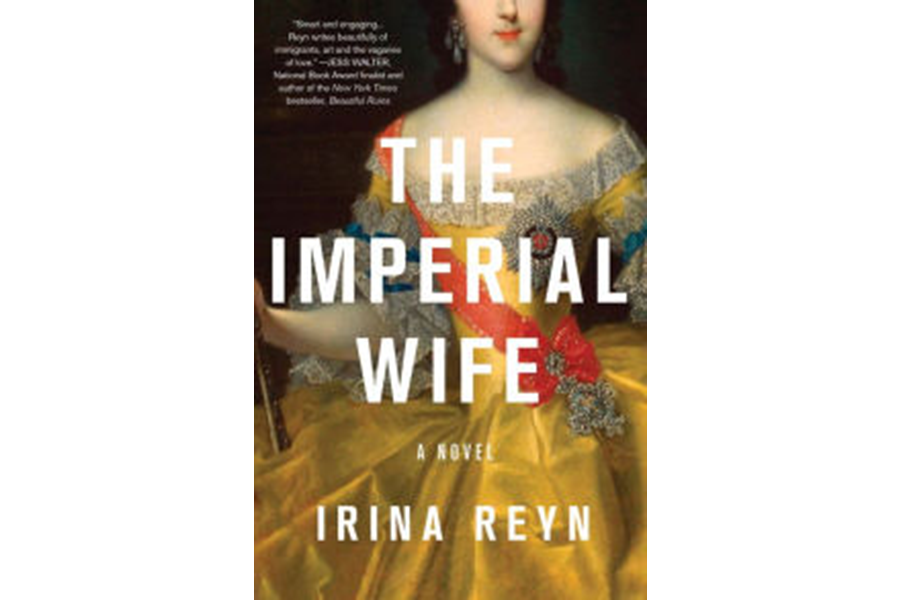

'The Imperial Wife' finds shades of Catherine the Great in a NY emigre

Loading...

Irina Reyn’s marvelous first novel, "What Happened to Anna K.," brought an Anna Karenina to life in the 21st century. Both Anna K. and Reyn's new heroine share some of their author’s biography: born in Moscow; a schoolgirl when she and her Russian-Jewish parents immigrated from the USSR; raised in Rego Park, Queens; beautiful and smart.

The Imperial Wife is about two wives, striving achievers who, unlike Anna Karenina, can’t help themselves from propping up the prima-donnaish men in their lives: “I’m used to people assuming I’m the alpha in my marriage. Yes, I am more competent, more efficient; taking care of others comes naturally to me. Faster to have me accomplish something than Carl with his lack of attention to details, his indecision. It was during our honeymoon that the terrible thought occurred to me. Weak.” Tanya is the immigrant girl who has never stopped needing to impress her self-sacrificing parents, her fellow students, and then, at her workplace, a Manhattan-based auction house, her colleagues, by always having the answers. By Tanya’s early thirties, the present day, she and her husband are in the midst of a crisis.

Chapter by chapter Tanya narrates her own story, which is without comment interspersed with excerpts from “Young Catherine,” Tanya’s broody husband’s novel about young Catherine the Great. The remarkable if not always beneficent empress of Russia (from 1762 until her death in 1796) came to Russia in 1744 from the German state of Holstein to marry her second-cousin, the tsar to be, Peter III. She was a “young girl arriving in a foreign land. A young girl who imagined herself selected for an extraordinary purpose.” But Catherine’s husband was a silly and immature boy-man who never grew up; shortly after his ascension to the throne, he was assassinated, with little love lost from the ambitious and savvy Catherine, who had no qualms taking the throne herself.

We’re reminded by those excerpts if not by Robert K. Massie’s excellent biography ("Catherine the Great: Portrait of a Woman," 2011) that the real empress was brilliant, bold, and, for a tyrant, relatively enlightened. Though an adopted daughter of the land, she became more Russian than her court and was for the most part beloved by her country of serfs.

The parallels between the heroines are neat and unforced. In a new land, Tanya, like Catherine before her, transforms herself and leaves her old world family behind: “Once, I imagined my professional successes would bring them the deepest delight, but at some point I realized I’ve gone too far, achieved too much, striven to become too entrenched, American. I needed to take steps to curb all that ambition. Because in overreaching their expectations I’ve turned myself separate from them, foreign.”

Meanwhile (that telltale adverb that suggests complications), what seems to be the authentic medal that Catherine was awarded for marrying Peter becomes the coveted long-lost object that finds its way to Tanya’s purview at the auction house. Can a wife be too smart, too accomplished, too successful to maintain the love and trust of an insecure husband? Catherine was and so is Tanya. The inscription on the empress’s medal reads: “By her works she is to her husband compared,” and both Catherine and Tanya know there’s no comparison. The medal soon pits two of President Putin’s oligarch-cronies against each other as well as Tanya herself against her husband.

As far as Tanya is concerned, "The Imperial Wife" is about her own marriage that looks good but isn’t: “When something awkward and unsayable enters a marriage, it plants its feet right in the middle, folds its arms and refuses to budge.” The “unsayable” details mean that the plot sometimes travels disguised as a Sherlock Holmes story. “Marriage,” reflects Tanya, “a thing that had once felt so inevitable, so stable, was now turning out to be the biggest mystery of my life.” The novel’s primary focus is the quandary of a woman who’s too good at solving other people’s problems, but I’m no Sherlock so I was halfway through the book before I figured out I was also reading a mystery of who did what when and why.

Just as Catherine’s mother had tried to get daughter to tone down her obvious intelligence, Tanya’s anxious old-world mother has forever warned Tanya that the display of her capability could lose her her beloved; despite the advice being almost wholly disregarded, it has lodged in Tanya’s consciousness in list format: “No man wants a daunting woman. No man wants a woman who earns more than him. No man wants a woman who is too opinionated. No man wants a woman who values career over family. No man wants a woman who is vocal about being confident, who makes the first move, who picks the date activity, who makes a reservation, who has male friends, who does not greet him in full makeup, who serves her own food first, who wears sneakers, who admits to being hungry, who reads too much, who drives while he’s in the passenger seat, who doesn’t cook, who’s messy, disorganized, complains, confronts, acts like a martyr, plays sports, watches sports, lounges, remembers past slights, fails to forgive.”

If the clever Reyn convinces us to appreciate the historical Catherine as a modern woman, she also encourages us to second-guess the thoroughly modern and undauntable Tanya.

Bob Blaisdell teaches English in Brooklyn and is writing a biography of Tolstoy.