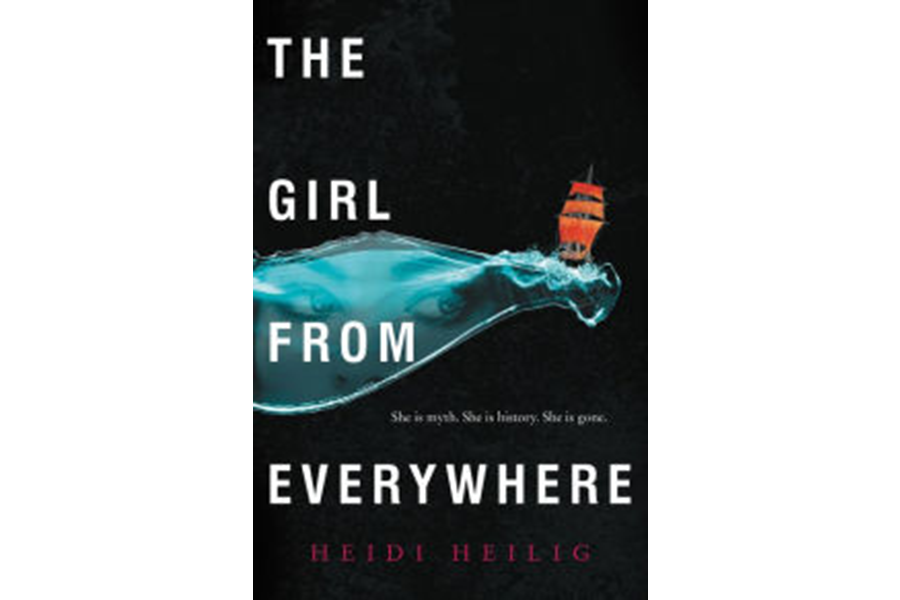

'The Girl from Everywhere' is rich with pirates, time travel, and cartography

Loading...

Ahoy, fellow YA enthusiasts! If and when you read The Girl From Everywhere, debut from Heidi Heilig, you’re probably going to encounter this conversation:

“So what’s your latest book about?”

“Um, a time-traveling pirate ship. And cartography. And mythology. And maybe parallel universes?”

“....Tell me more.”

Take my word for it, “The Girl From Everywhere” holds up to its arresting premise. It’s a truly exciting book, brimming with adventure, history, and sinuous potential.

The crew of the ship Temptation can go anywhere and anywhen, provided they have an accurate map of their destination. Want to see Krakatoa explode? Get them an 1883 map of Indonesia. (I don’t recommend it.) Watch the Spanish Armada disintegrate with the help of a 1588 English Channel map.

The world is the Temptation’s oyster. As long as the map is historically valid, the ship can even visit mythical places. Mount Olympus with Greek gods! Asgard, home of the Norse pantheon! The land of “One Thousand and One Nights”! (Say hi to Scheherezade for me, won’t you?)

They’ve seen it all. But their captain, Slate, has only one place and time in mind: Honolulu, 1868. That’s the last time he saw his wife, who died in childbirth while he was away on a time-venture. Slate has spent 16 years obsessively trying to reclaim the last time he was truly happy.

But as any good sci-fi fan can warn you, changing the past can have unforeseen consequences for the present.

Our protagonist is Slate’s daughter, Nix, now a teenager and the Temptation’s resident expert on cartography, history, and folklore. Nix has spent her entire life on the Temptation, forced to aid her father in his quest.

Slate is a compelling character, as befits a time-traveling sea captain. He’s wild, willful, at once single-minded and distracted, zealous, taut, and desperate. An opium junkie with kinetic charisma, he is there and yet not there in every scene.

If they get back to 1868 Hawaii, and her mother doesn’t die, what becomes of Nix? Will she get the happy family she’s dreamed of, or will she cease to exist? When Slate acquires the most promising map yet, Nix’s fears are poised to become reality.

I won’t sugarcoat it: This is one of the more labyrinthine plots I’ve met. But Heilig has a steady hand at the time-traveling tiller. Her use of adjective and metaphor is positively succulent.

Slate and Nix’s relationship suffers a constant push-pull. Nix detests many of his characteristics, while unwittingly echoing them. Take these nuggets from Nix, describing her father at his highest...

“Slate was there, clapping his hands together, the color high in his cheeks, and for a moment I glimpsed what my mother must have when she fell in love. Slate was as picturesque as any ruin.”

... and his lowest:

“There is something terrifying about seeing someone strong standing on the edge of the abyss, like a ship on the lip of a whirlpool where the whole sea plunges into the maw of Charybdis. There is that moment when they reach out – like a drowning man will – and if you’re within reach, they will pull you down with them.”

Nix’s best friend on the ship is Kashmir, a master pickpocket from mythical Persia. Kash and Nix are best friends, thick as thieves (sometimes literally). The self-assured, sarcastic sailor has some of the best lines in the book.

When an admirer visits the ship and assures Slate his intentions are honorable, Kashmir smiles thinly and says, “Don’t they say the road to hell is paved with honorable intentions?”

Nix shoots back, “That’s good intentions.”

“Ah yes, of course,” Kashmir replies smoothly. “But perhaps Mr. Hart can go to hell anyway.” #burn

I could go on and on.

The author’s research shines in this tale. History enthusiasts might weep sweet tears at the humbling number of references.

Global mythology, Hawaiian lore, classical allusions, linguistics, local mores, and historical events – they’re woven so subtly into the warp and weft of “Everywhere” that it averts gaudiness. If you know your classics, the references brighten the page like linguistic lemon juice. If not, the text unspools with an almost calligraphic flair.

Deep-set motifs include the following: loyalty (to family, self, country). Time (but not just eras: amount, pace, quality). Ethics (what’s right and wrong and gray all over?). Selflessness vs. self-preservation. Belief (its power, for good and evil).

“The Girl From Everywhere” is a bewilderingly good book. How is this spicy, lithe novel a debut? Folks, Heidi Heilig is one to watch.