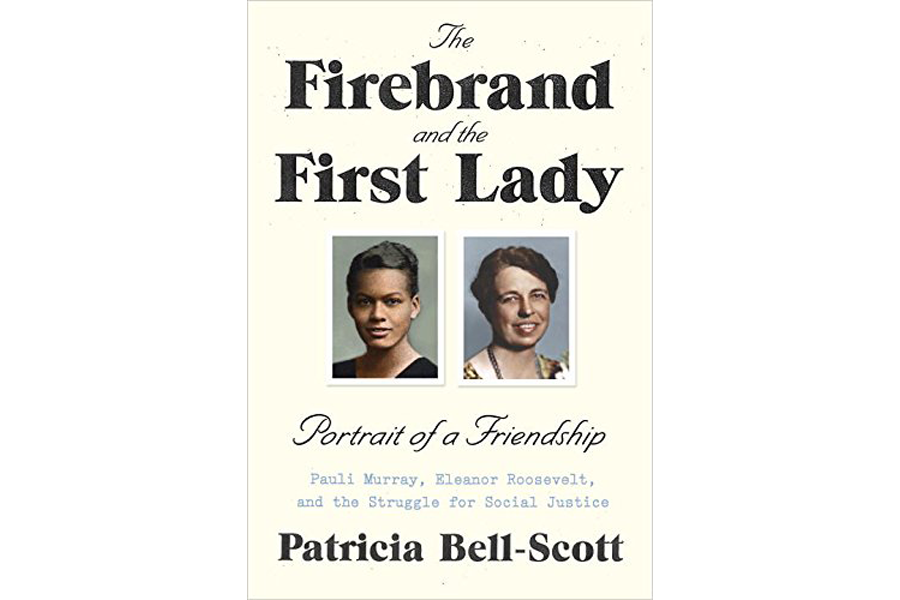

'The Firebrand and the First Lady': how two great women came together

Loading...

Born in 1910, and the granddaughter of a slave, Anna Pauline “Pauli” Murray was a complex individual, troubled throughout her life with both health and financial problems. In addition, she was a black gay feminist socialist who flirted with communism. None of the above were good for her career in mid-20th-century America.

And yet what a life she forged, one that would put her at the epicenter of the civil rights movement, marching hand in hand with fellow travelers like Martin Luther King Jr., Thurgood Marshall, Betty Friedan, and Eleanor Roosevelt.

Indeed, Murray was often ahead of the activist curve. In 1943, while a student at Howard University, she led a successful sit-in at a District of Columbia restaurant, which quickly agreed to serve African-Americans. Decades later, when the focus was on race relations and dismantling Jim Crow in the South, Murray drew attention to what she referred to as “Jane Crow,” scolding fellow civil rights leaders for relegating women in the movement to essentially the back of the bus.

The Firebrand and the First Lady is a thoroughly researched account of Murray’s peripatetic career as well as her friendship with Eleanor Roosevelt – another female activist who was also ambitious and had overcome odds. Both women, for example, were orphaned at a young age.

Patricia Bell-Scott, professor emerita at the University of Georgia, has done a yeomanlike job of bringing both of her subjects and their careers into sharp focus, especially where the strands of their lives intersect. A wonderful touch is the reprinting in full of many of the letters that the two women exchanged, as well as those Murray wrote to President Roosevelt – missives that were critical of his policies, or lack thereof, dealing with the problems black Americans faced. Murray, the author of two books, was a skilled writer and relentless advocate for many issues more commonly associated with the 1960s than with the 1930s and ’40s.

If Mrs. Roosevelt was to the left of her husband, tugging him in that direction, Murray was one of the people urging the first lady to pull harder. The two women initially came into contact via mail, as Murray, sagely enough, would send Mrs. Roosevelt copies of the letters she had mailed to her husband.

In 1938, Murray was affronted by Mr. Roosevelt’s speech at the University of North Carolina and his “coziness with white supremacy in the South.” In a letter, she pointed out to the president that her grandfather had lost an eye fighting for the Union in the Civil War and asserted that black Americans “were as much political refugees from the South as any of the Jews in Germany.”

The president never responded and he and Murray never met, but the first lady did reply. And eventually she would invite this relentless firebrand over for tea to her New York City apartment or to Val-Kill, her retreat in New York – and later to the White House. Mrs. Roosevelt sometimes could convince Mr. Roosevelt to weigh in on behalf of Murray’s causes. He urged the president of Harvard, his alma mater, to accept Murray as a law student. (He was not successful – Yale Law admitted her a few years later.)

Murray’s causes were many, including the case of Odell Waller, a young black sharecropper in Virginia charged with murdering his white employer and landlord. The two-year crusade in Waller’s defense included a rally at Madison Square Garden in New York City that attracted 20,000 supporters.

Murray’s career zigzags enough to induce vertigo in the reader. She was a teacher, a lawyer, a freelance writer, a poet, an editor, a minister, and one of the founders of the National Organization for Women; she labored for myriad social agencies and organizations such as the Negro People’s Committee to Aid Spanish Refugees and the Southern Tenant Farmers Union. The pay was invariably low.

At times she was unemployed and once rode the rails from California to New York like a hobo, passing as a man for safety’s sake.

Although hospitalized on occasion for exhaustion and various ailments, she always bounced back. She worked for a time in Liberia and taught law for five years at Brandeis University, giving up that cozy tenured position to earn a degree in theology so she could be ordained as an Episcopal priest, the first African-American woman to accomplish this.

Murray’s only constant was that she was always a foot soldier in the great battle for social justice. This book makes an important contribution to understanding Murray’s impact on the Roosevelts.

She would miss Mrs. Roosevelt dearly when her friend died in 1962. She even had warmed up to Mr. Roosevelt, writing to his wife after his death in 1945: “We have just heard. There is not one I’ve seen who has not expressed a physical illness over the disaster which has befallen each individual American today.”

David Holahan regularly reviews books for The Christian Science Monitor.