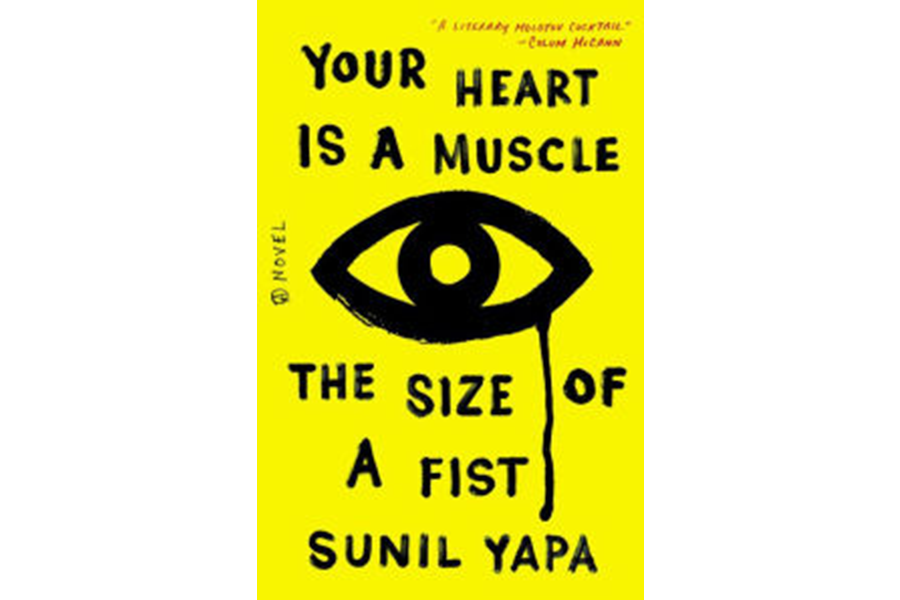

'Your Heart Is a Muscle the Size of a Fist' turns recent history into literature

Loading...

Early in Sunil Yapa’s coruscating, conscience-rousing novel about the 1999 World Trade Organization protests in Seattle, a Guatemalan-American policewoman named Julia observes a cop on horseback “messing with a protestor.” Eying him watchfully, she remembers her rookie year in Los Angeles, in 1992, when, in the aftermath of the Rodney King verdict, the city “lost its collective mind and was trying to burn itself to the ground.” In Watts, Julia felt some sympathy for the rioters but cuffed a looter who stole Pampers and a Pepsi anyway, “because that was the job.” She front-cuffed her, though, so the woman could drink her Pepsi on the way to jail, because, “sometimes you had to break the rules to hold true to a higher law.”

In Your Heart Is a Muscle the Size of a Fist, Yapa stalks that elusive higher law, hunting down its contradictions, its murk, and its hope by tracking its imprint on the thought processes of his characters on the first day of the Seattle protests, November 30, 1999. His suspenseful tick-tock runs not only hour-by-hour but mind-by-mind, his chapters alternating between the voices of cops, protestors, and an elderly WTO delegate from Sri Lanka (the native land of the author’s father), who cannot comprehend why protestors are impeding his journey toward the convention center.

When one activist spits on him, another stops to apologize, saying, “We’re out here to protect countries like yours.” The Sri Lankan muses, “Protect countries like mine? What did he imagine the Third World to be?” Later, confused cops will arrest him. Still later, he’ll get a meeting, but not the one he wants. The protestors fight for their idea of justice; the cops fight to enforce theirs. But in the words of one of Yapa’s main characters, Victor, a bookish, introspective, half-black teenage runaway, alienated from his family, his country, and himself: “What did that mean? Justice?”

As the crowds build, the chief of police, an upright widower named Bishop, vows to preserve order in Seattle, even though he feels a pang of nostalgia, as he surveys the protestors, for an “American life that was passing away, if not already gone, the belief that the world could be changed by marching in the streets.” Spotting an overaggressive cop, Bishop barks at him to cool down: “We are not going to start beating our own citizens,” he warns. But the chief confronts demonstrators, too. “Don’t make me hurt you people. Don’t make me do it,” he tells them. “This is my city. And I’m telling you we will bring those delegates safely through.”

The reader knows that the delegates won’t get through and that Seattle is not the cop’s city; but the reader also knows that one of the faces in the mob belongs to Bishop’s estranged adopted son, Victor, who ran away from home at 16, a year after his mother’s death, seeking “the secret and not-so-secret strands that connected his body in the here and now to worlds three continents away.” For three years, Victor had tried to “discover who he was” among Mexican factory workers, Andean protestors, Indian hunger strikers, smog-choked Shanghai passersby, and migrant farmers. Unable to define himself, he has returned to Seattle, where he hides out in a tent under an overpass, making no contact with his father. He joins the activists without quite meaning to, lured by the kindness of a radical revolutionary turned peacenik who tells him it’s not a protest, it’s a “direct action” and invites him to sit in lockdown, where chains, not strands, will bind him. As the police move in and outraged protestors chant “OUR COPS!!!” Victor marvels at the word our. “Did they really believe that?” he wonders. “The police protect money and power. They protect the few from the violence of the many. Do you have to be black or brown to know this?” Victor, as a “half-black brown boy” by his own assessment, embodies both the few and the many. “Where did he belong? To whom did he belong? He didn’t know.”

Today it’s hard to remember the shock of those Seattle protests, when 50,000 people appeared, as if out of nowhere, to oppose unfair international trade dynamics – an issue that had not drawn great public attention before then. The Seattle police, not anticipating the scale of the demonstration, had underestimated the need for crowd control. As the crisis escalated, they reacted with billy clubs, pepper spray, tear gas, and panic; soon, the National Guard was called in. Many Americans saw the protest through the lens of a few images of activists vandalizing shops, and some instinctively sided against the demonstrators as a result. Others saw footage of cops firing tear gas and rubber bullets and felt they were justified. Thomas L. Friedman, in an op-ed in the Times on December 1, 1999, deemed the protests “ridiculous” and called the protestors “a Noah’s ark of flat-earth advocates, protectionist trade unions and yuppies looking for their 1960’s fix.”

Reanimating the debacle nearly two decades on, Yapa shows less interest in nicknaming than in explaining the intense emotions that surrounded the protests, by letting each individual reveal the cast of their mind-set, without bias or preference. His novel demonstrates the great advantage that fiction has over journalism: the freedom to establish the facts, after the fact, and to set them in a context deepened by hindsight.

His gripping retelling brings to mind another significant protest – the largest in history – which occurred three years after Seattle and went strangely under-reported. In February 2003, in the jittery aftermath of 9/11, some 15 million people in hundreds of cities across the globe rallied to oppose the imminent US-led invasion of Iraq. In New York City speeches were given at Dag Hammarskjold Plaza, near the United Nations, but many who tried to attend encountered great obstacles. For one thing, the city – drawing a lesson from Seattle? – had denied a permit to anti-war marchers. For another, subway service between Brooklyn and Manhattan was suspended and was truncated within Manhattan proper, meaning that many ralliers had to walk miles to get to the plaza. Pushing through streets crammed with charter buses, the would-be attendees – benign, button-downed New Yorkers and suburbanites – met with police barricades when they tried to turn east toward the plaza. On foot and on horseback, cops surged among the crowd, shouting and muscling them westward. It’s frightening – as Yapa’s Julia knew – when a man in riot gear on a horse charges toward you, punches down your sign. Returning shakily home that day, I had turned on the television news and was stunned to find scant coverage.

Reading "Your Heart Is a Muscle the Size of a Fist," I wished illogically that I could have read it at the time of the 2003 demonstration, to be reassured that, if there is a peace rally and everybody comes but nobody covers it, its existence has not been negated, it can be revived through literature. The blurred crises of this country’s recent history, whether in Los Angeles, Seattle, New York, or any other city, deserve the clarifying focus of a novelist’s eye; the lens of the present is clouded. The Russian author Ludmila Ulitskaya wrote not long ago, “In some ways, literature is a more exact science than history. What a great writer says can become a historical truth.” She gave as an example Tolstoy’s description of the Battle of Borodino, in "War and Peace," which has replaced the official record in the public imagination.

Nobody would compare a Seattle protest to a Napoleonic war; but that does not diminish the feat that Yapa achieves with this remarkable, engrossing novel, subjecting history’s police log to the higher law of the writer’s vision.