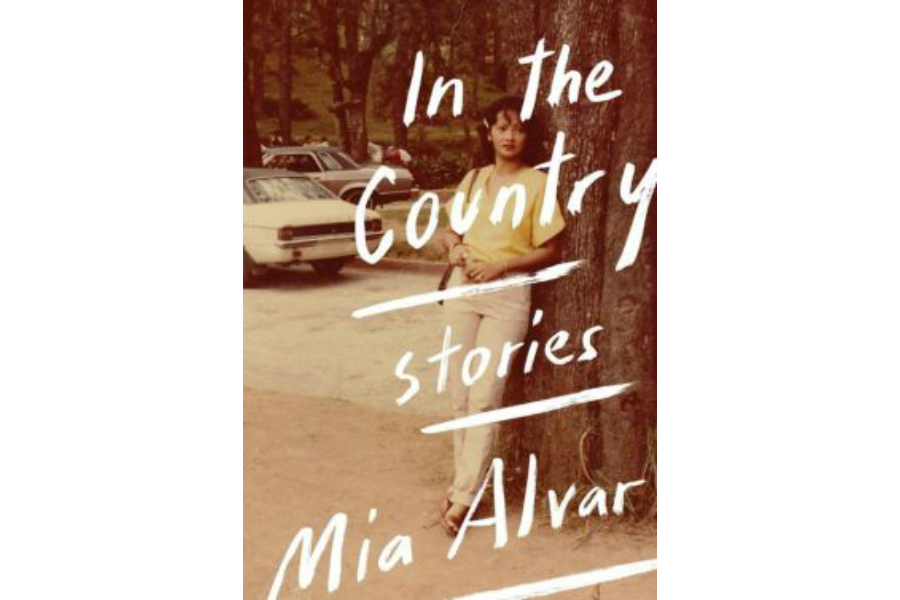

'In the Country' tells tales from the Filipino diaspora

Loading...

The thread that binds together the stories in Mia Alvar's debut collection In the Country is homeland, the “country” of the title being the Philippines even though many of these nine stories are set far away from the place itself.

Some of Alvar's characters have traveled all over the world – she confidently evokes settings from New York City to Riyadh – but all of them carry their country in their hearts, connected by ties of family and culture. In these nine stories, all of them so smoothly and successfully realized that it seems incredible that this volume is her fiction debut, many of Alvar's characters seek their fortunes far from home, although echoes of that home sound throughout their immigrant lives.

“But at these parties we spoke Tagalog even to the babies, who barely understood it, for the same reason we served pancit and not sharwarma,” a character reflects in “Shadow Families, “Between Arab bosses and Indian subordinates, British traffic laws and American television, we craved familiar flavors and the sound of a language we knew well.”

In the superbly affecting story “The Kontrabida,” a young hospital pharmacist finds himself smuggling American painkillers back to his parents' home in a Manila suburb, to help his father, whose medical prognosis has gone from dire to hopeless (“My money turned from doxorubicin and radiotherapy to oxygen tanks, air-conditioning, the dark brown bottles of morphine,” as Alvar writes, one of the many instances where this still-young author strikes a believably worldly-wise note), and even in the middle of his errands of mercy, this young man acidly reflects on his dual status: “the balikbayan, who worked hard and missed home but didn't complain, who'd moved up in New York but wasn't down on Manila.”

It's Alvar's speciality: the smart depiction of lives lived between two worlds.

This is never more vividly portrayed than in the collection's most accomplished story, “Esmeralda,” about a mild-mannered Filipino serving woman working in New York (one employer on Tuesdays, another on Wednesdays, Thursdays cleaning a loft in downtown, Fridays cleaning in brownstone uptown, etc.) who continually flashes back to her old life in Manila, as when she's taking a Manhattan bus crammed in with other commuters: “You sit Manila jeepney-style, six knees in a row – as if you're riding home from Nepa-Q-Mart once again, your cousin's children on your lap, the week's meat thawing at your feet, while strangers pass their fare through you up to the driver.”

When Esme indulges in a brief affair with an employer who works in one of the Twin Towers and then the 9/11 attacks happen, she reflexively prays and then just as reflexively castigates herself: “You know that bargains aren't prayers. This kind of pagan trade isn't what Jesus meant by sacrifice. Today, though, you'll try anything.”

The collection's longest story – virtually a novella – is “In the Country,” which spans more than a decade in the life of a Filipino nurse named Milagros Sandoval, is rendered every bit as confidently as “The Miracle Worker,” a much shorter story about a special education worker tasked with the impossible job of overcoming the physical and emotional handicaps of the daughter of a wealthy employer. It's a range that would be the envy of authors with 10 books under their belts, and all the stories are shot through with vivid glimpses of street life in Manila, as in “Legends of the White Lady”: “On the highway, skinny boys in wifebeaters dodged the traffic, some wearing flip-flops, others barefoot, their shins and calves dark with scabs.”

In the story “A Contract Overseas,” a young woman dreaming of attending college is almost involuntarily fascinated by the picaresque life of her brother, who takes a job driving a taxi in Riyadh and sharing a crowded apartment with pipeline workers, gardeners, servants, and fellow drivers. At one of her college classes, a student growls about the piecemeal, hopscotch nature of Filipino fiction. “What other way is there to writer about this country?” the exasperated young man asks. “Three hundred years under Spain, via Acapulco. Thirty years under the Americans and three under the Japanese. A history of fragments and confusion – 'chop suey' is the only style that captures it.”

It's a tough assessment, and any reader of "In the Country" will suspect it's offered with something of a half-smile, since there's nothing fragmentary or confusing about the stories in this remarkable debut. Other countries should be so fortunate in the quality of their "chop suey" expatriate literature.