Celebrated poet Jane Hirshfield explains poetry as ‘a truing of vision’

Loading...

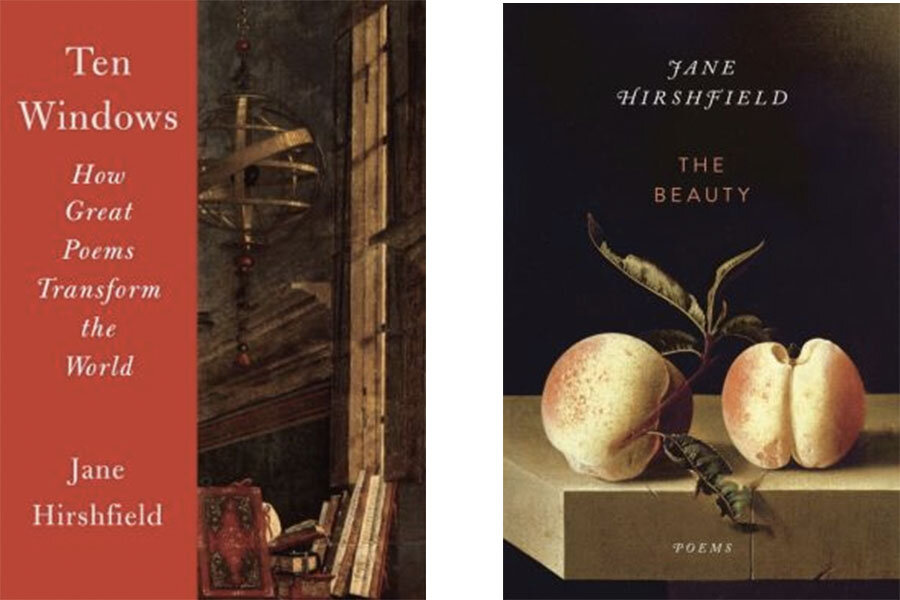

Jane Hirshfield’s poetry has always provided gleaming perspectives on the nature of life and what it means to be human. Now, with the publication of two new books, she is giving fans great reason to celebrate the art form during National Poetry Month and beyond.

Both sophisticated readers and novices may want to start with Ten Windows: How Great Poems Transform the World before dipping into The Beauty, Hirshfield’s eighth book of poems. The former, a compelling collection of essays, explores and explicates the creative process, while the latter demonstrates powerful writing in all its glory.

Hirshfield’s prose, like her verse, is immediately engaging because it brims with intelligence and artistry. Her pithy preface to “Ten Windows” begins with this: “Good art is a truing of vision, in the way a saw is trued in the saw shop, to cut more cleanly. It is also a changing. Entering a good poem, a person feels, tastes, hears, and thinks in altered ways. Why ask art into a life at all, if not to be transformed and enlarged by its presence and mysterious means?”

The essays that follow show how poets shape – and are shaped by – language and the intuitive urgings that give poetry its expansive power. Hirshfield, whose honors include a Guggenheim and the Poetry Center Book Award, writes with the conviction and ease of someone who has studied and loved great poems for more than 30 years. That rich background enables her to move effortlessly from broad strokes to in-depth observations about works by Hopkins, Basho, Keats, Dickinson, and other essential writers.

Some of the most important lessons come early in the book, such as the concept of poetic vision – or poetry’s eyes – introduced in Chapter 1. “This altered vision is the secret happiness of poems, of poets,” she writes. “It is as if the poem encounters the world and finds in it a hidden language, a Braille unreadable except when raised by the awakened imaginative mind.” Hirshfield helps people feel that language, moving quickly, deeply into foundational principles that allow both readers and writers to move ahead.

Each succeeding chapter introduces other essential building blocks, such as imagery, statements (complex and simple), and hiddenness or concealment. Hirshfield makes each topic so rich that readers don’t merely understand; they become part of the creative process, as if the poet were writing them. Even topics that might dissuade some people from reading poetry – chaos and grief, impermanence – are so beautifully presented that readers may reconsider their value as apertures into greater understanding.

As the book progresses, Hirshfield presents many kinds of openings, such as surprise, sudden endings, and what she calls windows.

“Many poems have a kind of window-moment in them – they change their direction of gaze in a way that suddenly opens a broadened landscape of meaning and feeling,” she explains. “Encountering such a moment, the reader breathes in some new infusion, as steeply perceptible as any physical window’s increase of light, scent, sound, or air.”

That concept is key to appreciating Hirshfield’s own poems in “The Beauty.” Here, as in previous collections, her writing is grounded in an awareness of life’s cycles and its transience. As she describes everyday scenes – mopping a floor, looking at corkboard, putting books near the foot of the bed – she looks beneath the surface to discover an inner-outer world.

Over and over the poems highlight the choices one makes about how to perceive an object or an experience, and what mental leaps to allow.

In the poem “Honey,” the speaker recalls that “Each morning I wake in strange country,/ my bed made of strange wood./ Time arrives clockless.”

Those vivid descriptions help the writing resonate, just as Hirshfield’s essays explain. More poignant moments, such as finding her late father’s handkerchiefs, demonstrate how tears can be transformative and can generate compassion, one of the most important things poems do for readers.

“The Beauty” shows Hirshfield at her best, using all of her tools and talents to create spare poems that open in striking, sometimes metaphysical ways. Treat yourself to this masterly work:

The way the green or blue or yellow in a painting

is simply green and yellow and blue,

and tree is, boat is, sky is

in them also –

There are worlds

in which nothing is adjective, everything noun.

This among them.

Even today – this falling day –

it might be so.

Footstep, footstep, footstep intimate on it.

Elizabeth Lund reviews poetry for The Christian Science Monitor and The Washington Post.