'The Great Leader and the Fighter Pilot' presents a riveting slice of North Korean history

Loading...

Writing one of the most difficult-to-read books ever – “Escape from Camp 14” (2012), about a young man’s harrowing odyssey from North Korea where he was bred as a labor camp slave – put Blaine Harden on bestseller lists around the world. One of the many readers to reach out to Harden about the book was a man who identified himself as Kenneth Rowe, who phoned Harden “[o]ut of the blue” to ask Harden if he had “ever heard of No Kum Sok and the MiG he stole from North Korea in 1953.”

When Blaine replied in the negative, Rowe “laughed a little and suggested that [Harden] should be better informed.”

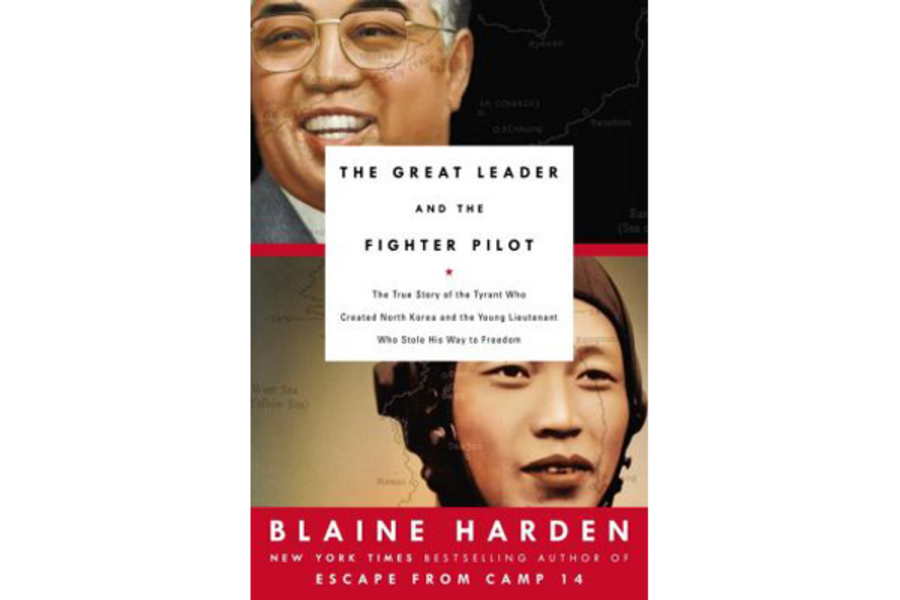

That call set into motion events that led Harden to write his latest title, The Great Leader and the Fighter Pilot. Rowe, it turned out, was No Kum Sok, the MiG-stealing North Korean pilot. Not only did Harden have much to learn about his titular fighter pilot, but his journalistic skills (Harden is the former Washington Post bureau chief for East Asia, Eastern Europe, and Africa) would add shocking, unknown details not included in Rowe’s 1996 memoir, “A MiG-15 to Freedom” … because Rowe himself was missing crucial information about his own life for over half a century.

Harden begins by examining the phenomenal cult of Kim Il Sung (grandfather of current North Korean leader Kim Jung Un) who literally rose atop a mountain of fertilizer in a pivotal 1948 speech to incite hungry masses. A year later he would claim himself as the Great Leader; a decade later he would "package himself as ‘the sun of mankind and the greatest man who ever appeared in the world.’”

Harden presents “[t]he legend of Kim Il Sung [as] part Robin Hood, part Harry Potter, and partly true.” That "partly true,” Harden shows, has roots in American military action: “For all their fakery and falsified history, three generations of dictators named Kim have found – and continue to find – legitimacy from a true and ghastly story of the Korean War: The US Air Force bombings and napalming of the North.”

The numbers are staggering: a Soviet post-war study showed American bombs damaged 85% of all structures in the North; as for citizens, the officially reported Northern population decline during the Korean War is 1.3 million, but according to General Curtis LeMay, head of the Strategic Air Command during the Korean War, “we killed off – what – twenty percent of the population [1.9 million people].” Such heinous disregard for North Korean lives was a “propaganda gift to the Kim family that keeps on giving.”

Harden's book shows the Great Leader cowering, murdering, begging, and rewriting his way to supreme power while the Fighter Pilot comes of age as the wealthy son of a Japanese-employed factories manager. No Kum Sok was 16 when he witnessed Kim Il Sung give his fertilizer-fueled speech. He learned early from his father that the best way to survive the Japanese occupation, then the incoming Kim regime, was to be “a Korean pragmatist, not a Japanese patriot.”

That pragmatism kept No alive, as he shed one identity after another: at 12, he was Okamura Kyoshi, desperate to volunteer his life to sink American fleets for Emperor Hirohito; one year later, he was “the most pro-American kid in his class” reveling in picture books in which “[t]he dog lived better than he did”; at 17, “[h]e projected Red enthusiasm at school” then lied about his family background to enter the naval academy on his second try. He survived the Korean War as the youngest pilot in North Korea’s air force.

No plotted for five years and eight months for his 17-minute escape on September 21, 1955. When he landed in South Korea, he had no idea that the US government had a $100,000 reward for the MiG-15 fighter jet in which he arrived. Getting his due through “Operation Moolah” would entail six months of interrogations in various international locations with multiple CIA agents, and – unknown to the fighter pilot until 60 years later – exposing President Eisenhower’s reluctance to uphold US military promises. No would morph yet again as Kenny No, an American engineering student, and decades later, present himself as the cold-calling retired octogenarian businessman Kenneth Rowe from Daytona Beach, Florida, who challenged Harden to learn more.

The cover might be stamped "nonfiction," but “Great” reads like an impossible-to-put down thriller. Harden showcases a cast of legendary liars – and his determination to expose the truth leaves very few standing. Beyond the hard-core facts, figures, documents, and official verbiage, Harden adds an accessible vernacular – not to mention just enough well-placed snark – to create the bestselling pot-boiler this book is destined to be.

Terry Hong writes BookDragon, a book review blog for the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center.