'The Top of His Game' showcases the remarkable career of sports writer W.C. Heinz

Loading...

Maybe you missed him somehow. He co-wrote “MASH” under a pseudonym. He banged out crisp dispatches as a young man during World War II. Then he came home and became one of the great columnists and profile writers of the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, working for major New York dailies and crafting deeply reported portraits of boxers and ballplayers for the likes of True, Collier’s and Esquire, among many others.

Ernest Hemingway praised his boxing novel, “The Professional.” So did Elmore Leonard. Later, David Halberstam helped bring his work to a new generation by including three of his stories – more than anyone else – in "The Best American Sports Writing of the Century," an anthology edited by Halberstam and published in 1999. The following year, Sports Illustrated dubbed him “Heavyweight champion of the word” in a poignant profile by Jeff MacGregor.

All of the above is a long way of saying: Here’s to W.C. Heinz. During 93 years of life, Heinz, who died in February 2008, poured his heart into a writing career that left his colleagues in awe.

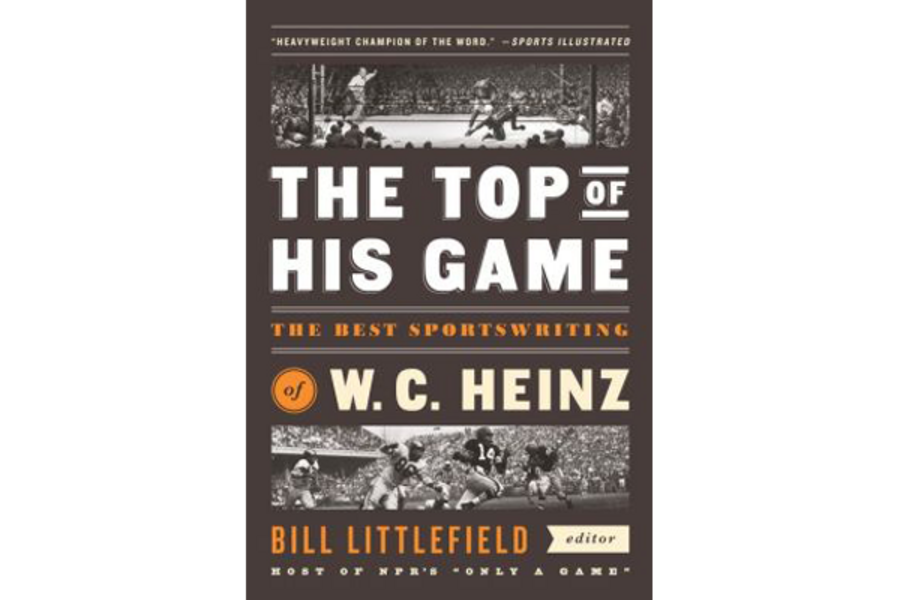

The Library of America, in a collection edited by National Public Radio sports commentator Bill Littlefield, hopes to bring Heinz to new generations of readers with the newly released The Top of His Game: The Best Sportswriting of W.C. Heinz.

Newspaper columns, magazine profiles and chapters from Heinz’s 1979 book “Once They Heard the Cheers” – which found him re-visiting some of his favorite interview subjects – fill these pages, introducing Heinz to some and reminding others of his brilliance.

Enough of the accolades and the résumé. Heinz would, as ever, prefer showing rather than telling.

What better way to show than this? Here, then, is the first paragraph of Heinz’s profile of the long-forgotten, troubled New York boxer Al “Bummy” Davis: “It’s a funny thing about people. People will hate a guy all his life for what he is, but the minute he dies for it they make him out a hero and they go around saying that maybe he wasn’t such a bad guy after all because he sure was willing to go the distance for whatever he believed or whatever he was.”

If you prefer second paragraphs, take a look at this one from “The Rocky Road of Pistol Pete,” a 1958 profile of the injury-plagued Brooklyn Dodgers outfielder Pete Reiser. Here is what Heinz tells us by way of introduction: “Maybe Pete Reiser was the purest ballplayer of all time. I don’t know. There is no exact way of measuring such a thing, but when a man of incomparable skills, with full knowledge of what he is doing, destroys those skills and puts his life on the line in the pursuit of his endeavor as no other man in his game ever has, perhaps he is the truest of them all.”

Resistance to these sentences is futile. Heinz, again and again, follows boxers, trainers, jockeys, ballplayers, and coaches in and out of gyms, locker rooms, bars, and even their parents’ houses, collecting personality tics, physical and mental struggles and, more than anything, the sound and language of sports heroes and has-beens.

Pairing careful reporting with his warm writing voice, Heinz becomes an amiable tour guide for sports fans, taking them into the frantic world of boxer Rocky Graziano the day of a bout, relating the anguish of an injured race horse being euthanized (“There was a short, sharp sound and the colt toppled onto his left side, his eyes staring, his legs straight out, the free legs quivering”) and, in his 1979 book, reflecting on how he broke the news to his editors upon his return from war reporting that he wanted to cover sports and not national politics.

The latter example went like this, Heinz writes. “How do you tell them? They have put on the party and raised the toasts and now, with the music rising and everyone standing and applauding they bring it in, all decorated and with the candles on it all ablaze. How do you tell them that they must have been thinking of someone else, because that’s not your name on it and it’s not your cake?”

Reading the collection includes not just the delights of Heinz’s graceful writing, but also insight into how different the sports world was. The heavy emphasis on horse racing, boxing, and baseball reflect a bygone era. Whoever the W.C. Heinz of the 21st century might be, he or she is much likelier to be a chronicler of the NFL, the NBA, and college basketball.

Then, too, the chances of any journalist being granted the kind of time and access Heinz enjoyed – and worked tirelessly to make the most of – are all but nil. Beyond those notable exceptions, there is the ever-delicate matter of the pitch-perfect quotes that filled the stories written by Heinz, A.J. Liebling, and other masters of narrative nonfiction around the middle of the 20th century.

In his introduction, Littlefield recounts Heinz’s recollection of taking a friend to the boxing gym in New York as Heinz searched for a column subject.

The next day, the friend read a column by Heinz on the boxing manager Jack Hurley, one of the people encountered at the gym.

“Bill,” the friend told Heinz (the writer was known to his friends as Bill), “I don’t know how you do it. At the gym, you didn’t take a single note. Yet in today’s column, you had everything that manager said, word for word. You must have the greatest memory in the world.”

Heinz laughed about the conversation years later and said his friend didn’t realize his method. What his column did was recount “the rhythm of what the manager said, the sound and the feel of it.” This becomes slippery territory when quotation marks are used, as they often were, but as for the writing and the heart, and the indelible character sketches, Heinz’s work is nothing but a knockout.