'I Think You’re Totally Wrong' pits a former student against his one-time writing professor

Loading...

For many of us, a class (or classes) with a particular professor was not only one of the decisive experiences of college, but also one that echoed through the first decades of adulthood. Just as we hoped he (or she) would be impressed with the brilliance of our seminar papers or the elegance of our proofs, we’re also wondering what they think as we start our first career, begin getting published, or complete our dissertation.

After graduation author Caleb Powell kept in touch with his undergraduate writing professor David Shields. In his post-college years Powell worked construction, taught English overseas and traveled extensively before getting married and gradually beginning to publish short fiction – a life course starkly different from that of Shields, who has spent the entirety of his adult life in academe and has been consistently prolific, writing 14 critically acclaimed books over the course of 30 years. In 2011 they agreed to spend a long weekend together, ostensibly to discuss the dilemma posed by Yeats: “man is forced to choose/ Perfection of the life, or of the work.”

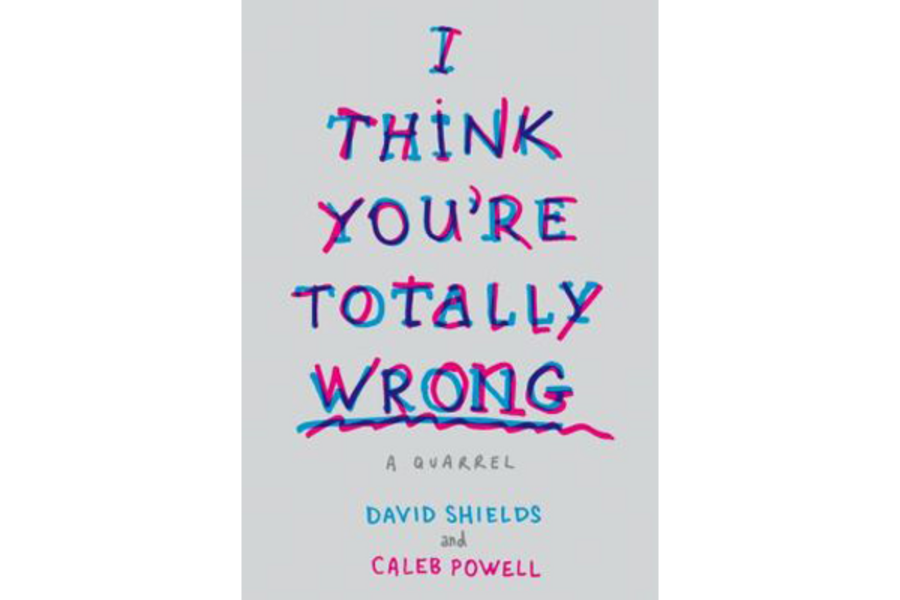

The premise – a middle-aged writer whose career has only just begun and his onetime professor reflecting together on how they’ve spent the intervening years – could have resulted in a book that was both stimulating and moving, a sort of "Tuesdays with Morrie" for people who love literary types. However, the resulting book – I Think You’re Totally Wrong: A Quarrel – is both problematic and frustrating.

First, Powell seems to accept without question that the dilemma posed by Yeats is inevitable. Second, in his early 40s Powell seems too young to be questioning his supposed choice of life over art: many writers’ careers begin in their 60s. Third, I reject the (implied) premise that a man with the personal history of David Shields hasn’t “had a life.” He’s had a stimulating career, is happily married and has a daughter he clearly adores. By even the most simplistic rubrics of what constitutes “a life” Shields has done quite well.

Third, like most actual conversations, "I Think You’re Totally Wrong" is quite rambling – “rambling” as opposed to “wide ranging,” which is what they seem to have been aiming for. This isn’t "My Dinner with Andre" (which Powell and Shields, in an annoying act of self-consciousness, actually watch together over the weekend).

To be fair, "I Think You’re Totally Wrong" has some engaging passages. Both Powell and Shields are quite intelligent and erudite, and at its best the book has the charm of eavesdropping on the coffee shop conversation of two bright, bookish people. They discuss Jonathan Franzen (of whom they’re rightly dismissive), and David Foster Wallace (whom they rightly admire), as well as Noam Chomsky, Dale Peck, J.M. Coetzee, and Camus. They talk about literary fiction’s place (or lack of one) in contemporary society, the ethics of meat-eating, and the problems inherent in writing about sex.

But it’s unfortunately telling that the passage in this book I revisit and think about most is actually a quote from Jonathan Lethem: “Before I can begin to discuss the kinds of questions that people normally call ‘politics,’ I would have to solve perceptual and mental and emotional confusions that seem to me to so surround every discourse that I certainly haven’t gotten anywhere close to ‘politics’ yet.” And that quote provides one of the keys to what’s wrong with this book.

Both Powell and Shields (like all of us) have confusions galore but never probe deeply enough to solve them. They might have started by trying to define what exactly they mean by “art” and by “life” – an impossible endeavor, but one that could have been fascinating to follow. And while Shields provides some interesting insights into his artistic goals and is at times brutally honest about his personal life, Powell simply isn’t a worthy foil. At times he sounds like a pretentious undergraduate, spouting facile faux-witty remarks such as, “I’d rather be insulted and dismissed by a genius than praised by an idiot,” or provocatively arguing that corporations are people because they employ so many of them. I’ll give Powell enough credit to assume these and other remarks are purely performative: perhaps his own mental and perceptual confusions make him think readers want or expect argument for argument’s sake from a man spending time with an old professor. But his stances are neither entertaining nor stimulating: they’re just annoying.

"I Think You’re Totally Wrong" could have been much better than it is. But Shields probably needed a better sparring partner for that to have happened.