'The Secret History of Wonder Woman' combines biography and cultural history to tell the story of Wonder Woman and her creator

Loading...

At New York’s Harvard Club in 1937, a prominent psychologist named William Moulton Marston confidently declared that women would rule the world. He claimed that as women “develop as much ability for worldly success as they already have ability for love, they will clearly come to rule business and the nation and the world.”

The prediction struck many as outlandish, but Marston had already lived through periods of radical change in the rights of American women. When he was a freshman at Harvard University in 1911, the school was so reluctant to support women’s rights that it banned the British suffragist Emmeline Pankhurst from speaking anywhere on campus. Pankhurst spoke instead at a nearby Cambridge venue, drawing a huge audience of students to a hall just across the street from Harvard Yard.

When the 19th amendment gave women the right to vote in May of 1919, Marston, newly married, had just concluded an affair with a suffragette from Chicago. His wife, Sadie Holloway, was also a vocal feminist. By the time he predicted women would rule the world, he was deeply in love with a young woman named Olive Byrne. She was the niece of Margaret Sanger, coiner of the term ‘birth control’ and one of the 20th-century’s most well-known feminists.

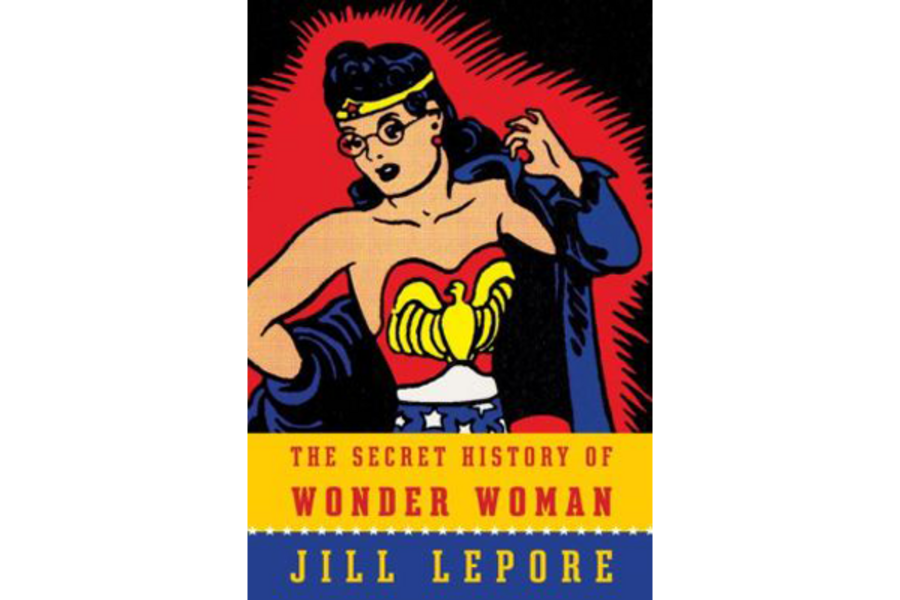

The women in Marston’s life led directly to his creation of the most famous female superhero of the past century: Wonder Woman. She debuted in D. C. Comics in 1941 and quickly gained a sizable following, trailing only Batman and Superman in popularity. From her outfit to her staunchly feminist sensibility, Wonder Woman reflects the influence of Marston’s tangled romantic and personal life. Jill Lepore’s new book, The Secret History of Wonder Woman, deftly combines biography and cultural history to trace the entwined stories of Marston, Wonder Woman, and 20th-century feminism.

Just as Wonder Woman made her debut, American women were entering the workforce in large numbers to perform many of the jobs vacated by men leaving to fight in World War II. Marston thought that women deserved the right to pursue professional careers at all times, not only in emergency circumstances. He saw his creation as feminist propaganda that could help a new generation support equal rights for women. He wanted Wonder Woman “to set up a standard among children and young people of strong, free, courageous womanhood; and to combat the idea that women are inferior to men, and to inspire girls to self-confidence and achievement in athletics, occupations and professions monopolized by men.”

Many of the early comics depict Wonder Woman rebuffing offers of marriage, saving men too weak to rescue themselves, and escaping from all manner of chains and snares meant to symbolize the oppression of women. Though immensely strong, Wonder Woman uses her incredible powers only to prevent harm to others; violence is a tactic rather than a pastime. In the strip’s origin story, Wonder Woman hails from a lost island populated by strong and beautiful women warriors. When she is especially worked up, she sometimes mutters curses like “Suffering Sappho!” or “By Hera!”

The primary villain, Dr. Psycho, was inspired by one of Marston’s Harvard professors, a psychologist who opposed female suffrage and thought that a moral woman belonged at home. Dr. Psycho delights in confining Wonder Woman with chains, ropes, and gags. Marston saw this as a metaphor for the bonds of a sexist society, but the persistence of the trope made some suspect the bondage motif had sexual undertones.

Whatever possible perversions lurked beneath its surface, Wonder Woman was strikingly progressive in many ways. In the 1970s, reflecting back on the legacy of the comics, the feminist Gloria Steinem said, “I am amazed by the strength of their feminist message.” In its early days, every issue included a centerfold called “Wonder Women of History” that profiled and praised historical figures like Susan B. Anthony.

Lepore – a professor of American history at Harvard, a New Yorker writer, and the author of "Book of Ages" – is an endlessly energetic and knowledgeable guide to the fascinating backstory of Wonder Woman. She’s particularly skillful at showing the subtle process by which personal details migrate from life into art. Early in his career as a psychologist, Marston developed a lie detection test based on blood pressure measurements. Though its scientific validity was highly dubious, the device attracted media attention and resurfaced throughout his career. In certain comics, Wonder Woman possesses a magical lasso that compels any captive to tell the truth. Marston had always hoped his lie detection test could promote the cause of justice; he fulfilled his wish when he created Wonder Woman.

Even as he was publicly championing the rights of women, Marston’s private life revealed a more complex reality. For most of his adult life he lived simultaneously with two women, Sadie Holloway and Olive Byrne, fathering two children with each. Marston had trouble keeping a job, but Holloway was a successful editor and executive. Byrne stayed home and raised all four of the children. One of the central challenges of 20th-century feminism was to reconcile the competing demands of motherhood and a career. The women Marston lived with did not solve this dilemma so much as subdivide it; Byrne handled the home front and Holloway had a career. Marston benefited from the situation without seeming to realize what it suggested about the ideal that women should not have to choose between a family and a career.

Marston wrote screenplays, practiced law, taught psychology, and tried to capitalize on his lie detection test. Nothing worked for very long, but his eclectic interests and unusual home life seeped into his work on Wonder Woman. The bracelets the character always wore, for instance, were inspired by two bracelets that Byrne wore in lieu of a wedding ring to commemorate her tie to Marston.

After Marston died in the late 1940s, the feminist agenda of Wonder Woman dropped away entirely. In the 1950s, the character became desperate to get married, worked as a secretary, and was constantly being saved from peril by strong men. She reflected rather than subverted dominant American values about gender. Holloway and Byrne, however, did not bow to convention. They continued living together and were thrilled to see the advances made by second wave feminists in the 1960s and 1970s. However gradually, wonder women were still defeating the likes of Dr. Psycho.