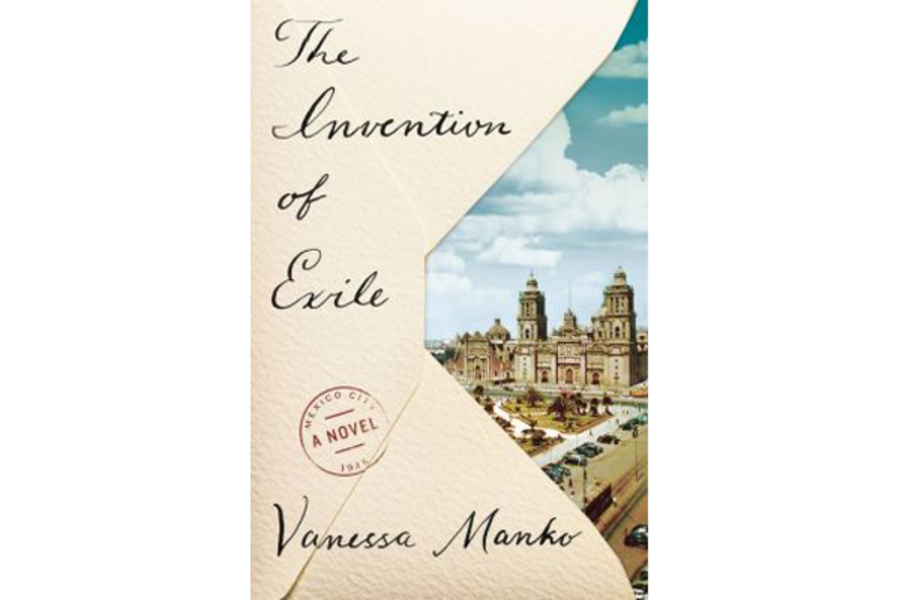

'The Invention of Exile' is a poignant tale of an immigrant's loss and longing

Loading...

For a convicted anarchist, Austin Voronkov is one of the most law-abiding people you’d ever meet.

The engineer lives, trapped in a stateless limbo, in Mexico City in 1948 in Vanessa Manko’s wistful, perceptive debut novel, The Invention of Exile. Austin repairs toasters and clocks to earn money, while concocting invention after invention, sure that the next one will be the breakthrough that will convince the United States to let him back across the border to reunite with his wife and three children.

“How does one live with longing?” Austin thinks. “He knows it. It was as if he were forever reaching, arms extended in a gesture of entreaty. Pulling on a rope, hand over hand, fist over fist, the rope only growing longer.”

Statelessness and the existential toll it takes on a psyche are the themes of Manko’s novel. The novel travels back and forth in time, showing how Austin ended up in Mexico City, while in 1948, Austin tries to evade a bureaucrat named Jack.

Austin immigrated to the US from Russia in 1913, where he meets Julia. He falls in love with her hands, first: “Julia, setting out plates as thin as coins.”

Austin, who worked at the Remington Arms Factory and the Hitchcock Gas Engine Company, believes in science and logic. Both things fail him utterly when he gets swept up in the Red Scare in 1920. With his poor English, his interrogation does not go well, and Austin finds himself confessing to being an anarchist. Rather than lose him, Julia renounces her American citizenship and the two marry at Ellis Island before being deported.

“By marrying him, Julia was no longer an American citizen. Austin was stateless, but, as far as he was concerned, they were Russian. Only Russia no longer existed. It had been stamped out,’’ Manko writes.

From Russia, the little family travels to France, Turkey, and then Mexico City, where they get a lovely, peaceful interlude living in a lighthouse in Mazatlan. Their three children are born in three different countries. Then Julia and the children are allowed back into the US, but Austin has to stay behind.

“They live two lives,” Janko writes of her separated lovers. “The life in their minds, the life at hand.”

The two try to maintain their marriage through letters, which grow more erratic as months stretch into years. “[S]ometimes a letter he sent would take two months, others two weeks, so their communication was nonlinear, circuitous, fragmented – letters sent like skipping stones over water.”

Midway through the novel, Manko shifts perspective, giving readers an understanding of just how tough the years in exile have been on Austin. Manko said she based Austin, with his threadbare dignity and desperate hope, on her grandfather, whom she never met.

“The Mexicans are a kind people, he has to admit, though he has learned to keep a distance, slide by people, let others slide off him.”

Convinced this was not the life he was meant for, Austin resolutely refuses to live at all, instead enduring the sepia days and trying to keep his shoes shined for his regular trips to the Embassy, hoping that this time, someone will let him go home to his family.