'Augustus: First Emperor of Rome' intrigues with its view of Roman politics

Loading...

After Caesar Augustus defeated his rival Mark Antony at the battle of Actium in 31 BC, the victor returned to Rome and greeted throngs of celebrating citizens. A man with a raven on his arm emerged from the crowd, and as he approached Caesar, the bird called out “Hail Caesar, victor imperator!” Charmed and flattered, Caesar bought the animal for a generous sum of money. Not long after, the man’s business partner approached with a second bird trained to exclaim “Hail Antony, victor imperator!” Amused by the affair, Caesar ordered the first man to split the revenue with his partner.

Like any good businessmen, the Roman bird trainers were hedging their bets. The victory that made Caesar Augustus the most powerful man in the ancient world was hardly inevitable; in fact his entire rise to power was improbable. The great nephew of the murdered Julius Caesar, Caesar Augustus was only 18 when he entered the violent and complex world of Roman politics. After his great uncle was assassinated in 44 BC, he faced so many formidable rivals that a sensible trainer probably would not have bothered to teach the birds his name at all.

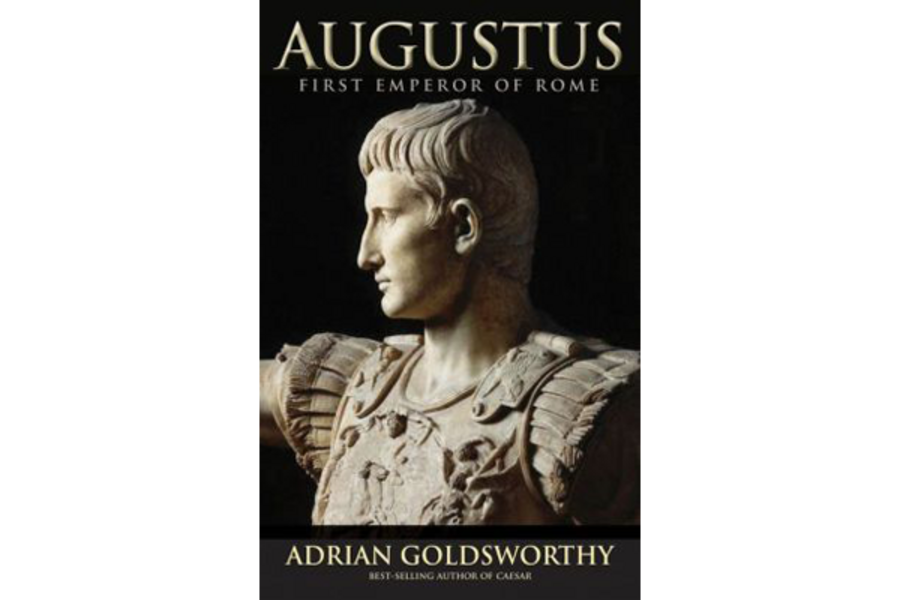

The dramatic rise and long rule of Caesar Augustus is the subject of Adrian Goldsworthy’s substantial new biography, Augustus: First Emperor of Rome. The book is a fascinating study of political life in ancient Rome, and the parallels with our own political system are numerous and interesting. But the discontinuities between America and the Roman Empire are just as revealing; most scandals in contemporary politics would seem utterly mundane by the standards of antiquity.

Political pedigree mattered then as now, and Caesar Augustus was keen to emphasize his relationship to the famous Julius Caesar. He quickly dispensed with his born name Octavius after he was designated principal heir in Julius Caesar’s will. Throughout his life he was known as Caesar, a constant reminder of his connection with the popular assassinated leader. Augustus was an honorific title later added to his name by vote of the Roman Senate. It’s a nice coincidence that Goldsworthy’s book is being published in August; the month is named in honor of his biography’s subject.

Augustus was a shrewd and effective manager of his own public image. It’s now easy to take for granted that images of political leaders decorate our currency – Augustus was among the first rulers to widely disseminate images of his own face on coins. His face was always depicted in the prime of life; no wrinkles or signs of aging were permitted. He was fairly small in stature, but he always tried to appear tall when he made public appearances.

Perhaps his most effective public relations technique was strategic false modesty. He loved to decline the ovations and triumphal ceremonies the Roman Senate showered on him after military success, and he refused to let his form appear in the sculpted company of the Olympic gods in the Roman pantheon. This added the luster of modesty to his reputation, but it did little to disguise the reality that he controlled the army and by proxy the entire Roman Empire.

It’s hard to imagine even the most ardent Democrats supporting the literal deification of Barack Obama or erecting small shrines in his honor throughout Washington DC. By contrast, after Julius Caesar was posthumously declared a god, Augustus, as his adopted son, became known as the son of god. Along with the other gods, he received dedications at small crossroads shrines throughout Rome.

Augustus tried launching an expensive military campaign in a distant region and claiming moderate disaster as resounding victory long before George W. Bush did. Campaigning in the Roman provinces occupied a great deal of his long career. Sometimes his motives were to secure access to the vital natural resource of grain, other times he fought to defend Roman honor against various real and imagined slights.

The motives for going to war might seem familiar, but the responsibility for its outcome rested heavily on the shoulders of an ancient leader. When the grain supply to Rome fell short of demand, Augustus dipped into his private fortune to fund distributions of grain to 250,000 citizens. Only a very unusual American president would spend his own money to pay for American citizens’ gasoline after a failed intervention in the Middle East.

Goldsworthy’s authoritative biography of Augustus encompasses not only the life of Rome’s first emperor, but also the broader social and political climate in which he maneuvered. It’s interesting to learn, for instance, that the filibuster was already an established stalling technique in the Roman Senate, and that our word candidate derives from the Latin phrase toga candidata, which refers to the white toga worn by those seeking office.

However familiar life and politics in ancient Rome can seem, certain details remind us that we’re confronting a culture that is also distant and strange. In his old age, Augustus exposed his infant grandson because the baby was born to his daughter from an adulterous affair. Exposing unwanted babies after birth was a common practice in ancient Rome, as was adultery among members of the ruling class. Leaving the results of adultery alive was not only bad publicity, there was also the chance that the infant might eventually become a rival to Augustus’ heirs. The child was only one of countless casualties of a successful and often ruthless political career.