'Price of Fame' continues to chronicle the remarkable life of playwright Clare Boothe Luce

Loading...

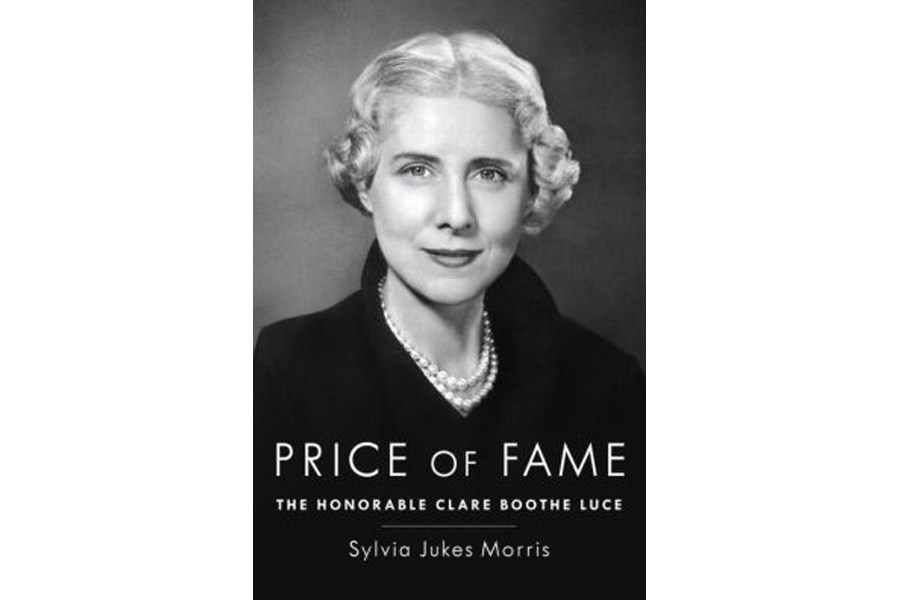

There is something slightly inapposite about the subtitle of the second volume of Sylvia Jukes Morris’s brilliant biography of playwright and public servant Clare Boothe Luce (1903-1987). After finishing Price of Fame: The Honorable Clare Boothe Luce, few readers will find a term as dull as “The Honorable” to be befitting so spirited a personage. “The Beguiling” or “The Buoyant” would be more like it – or maybe, for the woman who negotiated both the boards of Broadway and political office, “The Groundbreaking.” “The idea that anyone ever condescended to women in a century in which she lived is preposterous,” said William F. Buckley.

Out-of-place subtitle aside, Morris wastes no time in establishing Luce’s nonpareil qualities. The book, which tracks the last half of its subject’s life with dexterity, opens with the arrival in Washington, D.C., of Connecticut’s newest congresswoman in 1943. “Clare Boothe Luce” – even her name is uncommonly alliterative – “was by far the smartest, most famous, and most glamorous member of the House of Representatives,” Morris writes on the first page. But Luce was usually a room’s brightest star, whether in Congress or the Palazzo Margherita, where she toiled as Ambassador to Italy in the mid-1950s.

For readers who missed the first volume of Morris’s biography, “Rage for Fame,” published in 1997, a helpful overview brings us up to speed. In short order, we learn of Luce’s unsuccessful first marriage (to George Brokaw); her more notable second union (to Time and Life publisher Henry R. Luce); and her auspicious literary resume, a high point of which was her play "The Women," a Great White Way sensation in 1936.

Morris also emphasizes Luce’s intrepid overseas reporting in the early 1940s, including stories on the Sino-Japanese War and General Douglas MacArthur. Morris writes that the global character of Luce’s work “had been a major factor in her election to Congress,” and her travels did not come to an end once she got there, as she toured fronts in Europe. In 1945, she accompanied a delegation to the Nazi concentration camps – the most haunting passage in the book. She spoke about the experience in Congress upon her return: “Existence for human beings at Buchenwald, Nordhausen, Bergen-Belsen, Ohrdruf, Langenstein, Dachau and other extermination centers was a descent into the bowels of hell.”

The most surprising revelation about Luce’s congressional career was that this famous conservative was not, as Morris puts it, “shy of crossing party lines.” Without sacrificing her core beliefs, particularly her anti-Communism, she took bold, unexpected positions, including a stirring repudiation of imperialism. In an address to the India League of America, she argued forcefully against “lift[ing] a finger to help the British defeat the Indians in their fight for freedom.” By the end of her two terms, Morris writes, “Representative Luce could take credit for eighteen major initiatives espousing the causes of human rights: equal pay for equal work, racial and sexual fairness, profit sharing, and rehabilitation of veterans.”

Morris is equally thorough in recounting Luce’s ambassadorship, and in spite of all of the politicking to keep track of, also documents the last flickerings of her show-business career, including a tantalizing, never-produced screenplay of C. S. Lewis’s "The Screwtape Letters" and a 1970 update of "A Doll’s House," the one-act play "Slam the Door Softly." Far more compelling, however, is her telling of the major sorrow in Luce’s life. In 1944, her only daughter, Ann Clare Brokaw, was killed in a grisly car accident in Palo Alto, Calif., at the age of 19.

With her non-committal Episcopalianism, Luce had few beliefs to lean on, writing in a letter that she harbored “a grief too deep for words.” At the urging of a correspondent, Father Edward Wiatrak, she went to Monsignor Fulton J. Sheen for help. “No doubt you have heard him on the radio,” Wiatrak told Luce. Thus began a five-month spiritual rendezvous between two outsize figures of midcentury American life, with Sheen providing Luce instruction as she prepared to enter the Catholic Church. “As ‘homework,’” Morris writes, “Sheen recommended studying the New Testament, especially the 36,450 words of Christ.” Sheen may have been a tough teacher, but Luce was a willing catechumen. “No man could go to Clare and argue her into the faith,” Sheen said. “Heaven had to knock her over.”

Luce was as serious about her faith as she was about civil rights. But Morris never lets us forget that she was also a wit par excellence – just watch the fine film version of "The Women" or read the gems sprinkled throughout “Price of Fame”: “The difference between an optimist and a pessimist is that the pessimist is usually better informed”; “The only thing worse than having no family is having family”; or, on being jumped upon by Sheen’s St. Bernard, “You remind me of someone. Who is it? Oh I know – my first husband.” In that spirit, perhaps it is best to let Luce herself wryly take stock of her rarefied, multi-tasking life. In 1943, writing to a beau of her daughter’s about the “false picture [Ann] has of her world – and ours,” Luce warns him that he can’t possibly live up to it – “unless you become a national military hero overnight, write a great opera or novel, become managing editor of Time, be appointed ambassador to Spain, or inherit five millions....”

Clare Boothe Luce was prescient, too – it would be another ten years before she made ambassador.

Peter Tonguette’s criticism has appeared in The Wall Street Journal, The Weekly Standard, National Review, and many other publications.