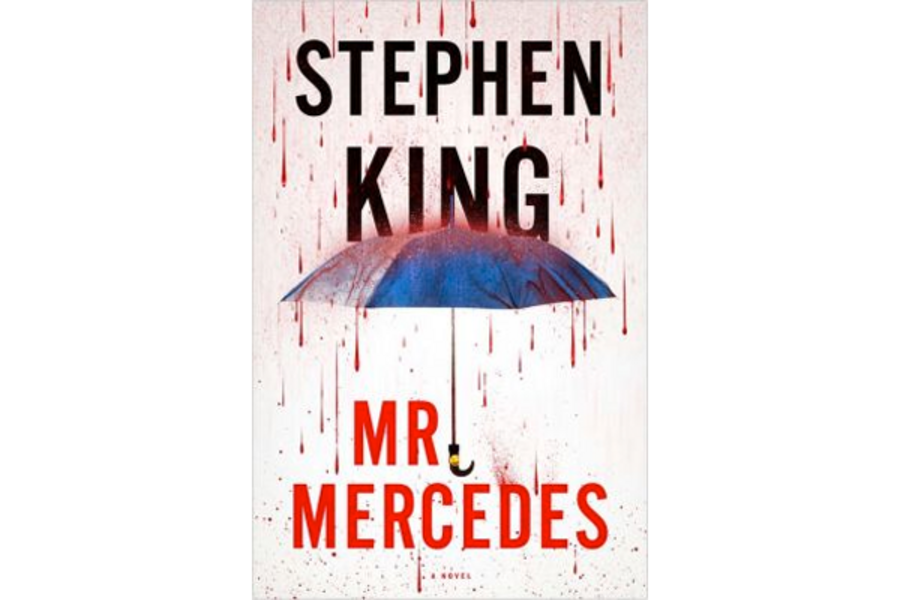

'Mr. Mercedes' is Stephen King at his pop-fiction best

Loading...

Even Stephen – wait, that’s a problem. Put it this way: Stephen King’s literary portfolio overwhelms even his publisher. Under his photo on the jacket of his latest novel, he is described as “the author of more than fifty books ….”

And, of late, King has had a hot creative hand. Similar to what Philip Roth did during the late 1990s and into the first decade of the millennium (think "American Pastoral" and "The Plot Against America," among others), King seems to have discovered a balance of relentless work ethic, mastery of his craft, and free-flowing ideas.

Consider this: Since 2008, King has published one of his best short-story collections ("Just After Sunset"), a collection of character-driven tales of suspense ("Full Dark, No Stars"), a clever alternative history ("11/22/63"), a mammoth blend of sci-fi and political satire ("Under the Dome"), and a harrowing account of addiction posing as a horror novel ("Dr. Sleep"). And that’s not even a comprehensive account of his writing during that period.

The description above offers a glimpse of King’s diversity. He does many things well, but the reason Stephen King became a brand name 40 years ago was because of his ability to take ordinary people and put them extraordinary situations — and never take his foot off the narrative pedal.

Think of Mr. Mercedes as an AC/DC song: uncluttered, chugging with momentum, and a lot harder to pull off than it looks. Or sounds.

Those who love and loathe King’s works will smile for different reasons at this comparison, of course. (Spare me the reminder of "Maximum Overdrive," the 1986 movie collaboration between novice director King and the band, cinematic schlock even the stellar theme song couldn’t come anywhere near rescuing.)

This is pop fiction’s version of arena rock – and even ends with a bang at an arena concert.

King begins his story with a cattle-call job fair in a Midwestern city in 2009. Then, just as dawn approaches, a Mercedes slams into the crowd, killing eight people, including a single mom and her baby, and injuring many more.

From there, matters get nasty. Yes, you read that right.

Bill Hodges, a recently retired detective who was assigned to the unsolved Mercedes Killer case, sits in his recliner six months after retiring. When the reader meets Hodges, the former policeman has been reduced to watching afternoon TV, putting on too many pounds, and caressing a gun while pondering suicide. Soon enough, King gives him reason to live: a taunting letter from the Mercedes Killer, who has been watching Hodges and hopes to push the retired detective to kill himself.

With that, King launches a white-knuckle chase filled with trademark pop-culture smarts, memorable characters, and accelerating tension.

Brady, the boy-man who behind the Mercedes murders, is pathetic, frightening, and damaged. He works two jobs: one at a big-box electronics store making computer-repair house calls and the other driving an ice-cream truck in the retired detective’s neighborhood.

King all but revels in sharing the tortured thoughts Brady entertains on a near-constant basis. “[Brady] almost pities them,” King writes. “They are people of little vision, as stupid as ants crawling around their hill. A mass killer’s serving them ice cream, and they have no idea.”

Brady has an unusual relationship with his alcoholic mother (of course he still lives at home well into his 20s), not to mention online alter egos operating from his high-tech basement hideaway.

As with so many King novels, a motley crew of ordinary, flawed, but well-intentioned people find themselves thrown together with a long-shot chance of preventing more deaths. This time, a mid-40s bipolar woman and a 17-year-old African-American teenager fond of mocking racial stereotypes are part of the mix.

Most of all, King excels when it comes to the verisimilitude of day-to-day life. A little NASCAR, a dose of psychobabble on TV, ruminations on how few of us have any clue how much of our online selves can and are being traced – King sprinkles these into the thoughts of each character, making them vivid. Another favored authorial trick: peppering each character’s thoughts with the quotidian phrases and quips so many of us collect subconsciously, mash-ups of movies and commercial jingles and whatever conversation we happen to be having with ourselves.

When the retired policeman begins some light surveillance while rationalizing to himself that he isn’t going to be one of those cops who can’t give up the job, a private security guard pulls his car behind Hodges’ and approaches.

Hodges, watching the guard approach, labels him Crewcut and, after Crewcut tells Hodges he has been parked – for a long time – outside the home of the wealthy woman whose Mercedes was stolen to carry out the job-fair killings, the policeman’s thoughts wander.

"Hodges glances at his watch and sees this is true. It’s almost four-thirty. Given the rush-hour traffic downtown, he’ll be lucky to get home in time to watch Scott Pelley on CBS Evening News. He used to watch NBC until he decided Brian Williams was a good-natured goof who’s too fond of YouTube videos. Not the sort of newscaster he wants when it seems like the whole world is falling apa–"

Self-referential winks and cameos, in the spirit of a Hitchcock movie, offer a bit of lagniappe to King devotees. Christine the killer Plymouth and Pennywise the Clown are mentioned in passing, with the latter described as “creepy as hell.” Those familiar with King’s son and fellow horror novelist, Joe Hill, will smile when they come across a minor character wearing a faded Judas Coyne T-shirt. Coyne, of course, is the fictional rock star haunted in Hill’s 2007 book, "Heart-Shaped Box."

King has written a hot rod of a novel, perfect for a few summer days at the pool. Mercedes-Benz commands drivers to demand “the best or nothing.” In pop-fiction terms, that motto still applies to Stephen King, too. With apologies to AC/DC, the highway to hell never felt so fun.

Erik Spanberg is a Monitor contributor.