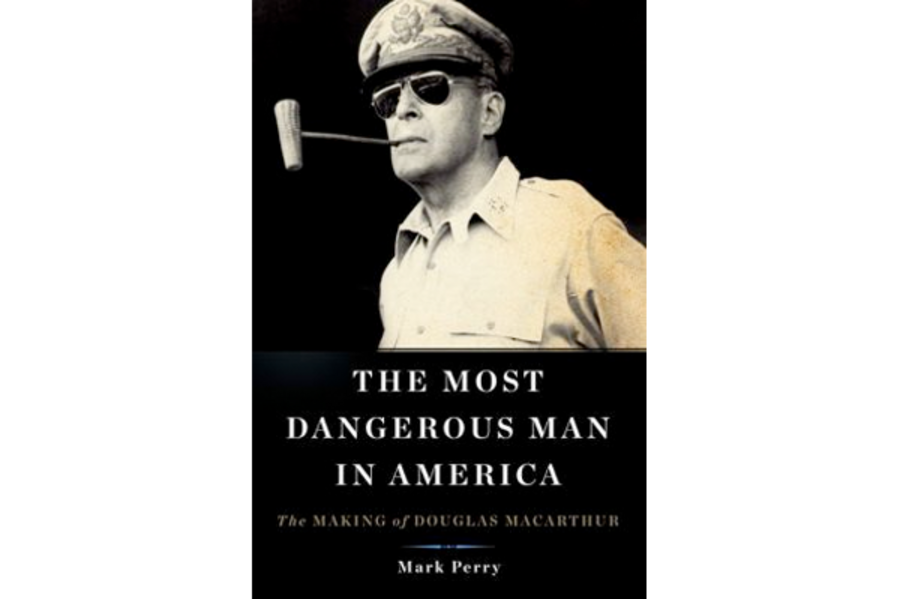

The Most Dangerous Man in America

Loading...

Here are handy guidelines to make it at your workplace. Rule No. 1: Do what your boss wants. Rule No. 2: Seriously, do what your boss wants. Who do you think you are, Gen. Douglas MacArthur?

Older Americans and history buffs know how MacArthur turned into a legendary case study in how not to treat a superior. He plotted against President Truman, got himself sacked, and landed another entry in Bartlett's Quotations with his timeless comment about what happens to old soldiers.

As an authoritative new biography explains, MacArthur was more than just a big mouth. Rule-breaker and grudge-keeper, master strategist and not-so-masterful manipulator, he represented brash American individualism at its best and worst.

The decline and fall of MacArthur has deeply affected the general's reputation, but historian Mark Perry is more interested in his life before he became a tainted hero. Perry is especially intrigued by the general's tense relationship with President Franklin Roosevelt, who had the gravitas and guts to closely oversee military efforts in World War II and manage MacArthur.

Neither task comes within miles of being easy.

Indeed, the quotation in the first half of the book's title – The Most Dangerous Man In America: The Making of Douglas MacArthur – comes courtesy of FDR himself.

The two men met in 1916 and "circled each other warily while feigning a comfortable friendship" for a couple of decades. During a chat with friends not long before he won the presidency in 1932, Roosevelt surprised everyone by declaring that Louisiana Governor Huey Long wasn't the most dangerous man in the country. No, he said, MacArthur fit the bill.

Why worry about this Wisconsin son of another war hero (MacArthur's prickly and outspoken father fought in the Civil War) and proud recipient of the highest grades at West Point since Robert E. Lee? Because MacArthur was trouble on two legs.

MacArthur had one success after another starting on the battlefield in World War I, and he rapidly worked his way up the ranks to army chief of staff. The only major blot on his record was a disastrous military take-down of veterans who protested in the nation's capital during the early years of the Depression.

And there lay the rub for Roosevelt. One man's courageous stand for law and order is another man's blot.

Roosevelt saw MacArthur as nothing less than a potential dictator, a golden-tongued and ruthless man who might rise as the country disintegrated.

But FDR had a plan to fight off potential usurpers. As he told an adviser, "We must tame these fellows, and make them useful to us."

While Perry's extensive descriptions of military strategy may be too dry for casual readers, no one needs to understand land and sea tactics to appreciate his glimpses into the inner lives of two men trying mightily to outmaneuver each other.

There are moments of flattery, such as when Roosevelt defanged MacArthur in a conversation by calling him "the conscience of the country." But the men engaged in subterfuge, too, and even outright hostility. In one of their endless battles over issues of military funding and strategy, MacArthur nearly lost his job when he dared to brutally question FDR to his face.

As he himself recalled, MacArthur told the president he hoped an American soldier dying in the field in the next "lost" war – "with an enemy bayonet through this belly, and an enemy foot on his dying throat" – would curse Roosevelt and not him.

The president exploded but quickly calmed down, a testament to Roosevelt's own brand of flexible steel. As he left, a chagrined MacArthur vomited on the steps of the White House.

War came on Dec. 7, 1941. In the darkest days, it seemed that the US would indeed lose whether Roosevelt and MacArthur got along or not. But their partnership, despite its strains, turned out to be crucial.

Not that things went smoothly as MacArthur tried to defend the Philippines and other parts of the Pacific against the Japanese. Personal vendettas spawnd unwise decisions, and MacArthur failed to shed the stubborn certainty that he was the smartest man in the room. "Shrewd, proud, remote, highly strung and vastly vain," as a British military officer put it, he often failed at getting others to do what he wanted them to.

But he inspired where it counted. Soldiers and citizens alike were drawn to his strength of purpose. Even Roosevelt, ever exasperated by a general who talks back like no one else he'd ever known, keenly understood MacArthur's expertise and value.

After FDR's death, MacArthur was undone by his tongue, the one that Harry Truman believed would even give God the what-for. Death threats after MacArthur's firing led his son to change his name forever.

Reporters have tried and failed to interview the son over the years, Perry writes. The MacArthurs, for once, are silent.

But the words and actions of "The Most Dangerous Man in America" live on. And we have many more of them to ponder thanks to this perceptive book.

Randy Dotinga is a Monitor contributor.